Sundays with Spielberg: Always (1989)

The master crashes and burns with this supernatural snoozefest.

A quick note before diving in to Always: Technically, after Empire of the Sun, Spielberg’s next film was Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, also in 1989. I’ve already covered the Indy sequels in one entry to avoid too much repetition. So, Always is the next up. I hope you enjoy!

Always is not Steven Spielberg’s worst film, but it might be his most uninteresting.

A romance without any heat, a spectacle that’s never spectacular, and a supernatural drama without a sense of awe, it’s a surprisingly banal entry in one of Hollywood’s greatest filmographies. Which is a shame because, on paper, it could have been something special.

The film is a remake of the 1943 Spencer Tracy melodrama A Guy Named Joe — a personal favorite of Spielberg and star Richard Dreyfuss — and its supernatural and emotional hooks would seem perfect for the director behind Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T. Just a few years removed from The Color Purple and Empire of the Sun, Spielberg had proven he could handle adult subject matter, and it’s intriguing to think about what a director known for cinematic magic could bring to a story about regret, longing and mortality.

Unfortunately, the answer is a dull mix of gauzy romance and empty noise, with none of the wit or transcendence that crackled through Spielberg’s earlier work.

A lot of fire, no sparks

Always tells the story of Pete Sandich (Richard Dreyfuss), a hotshot pilot who flies modified WWII planes to combat forest fires. Pete’s reckless, constantly taking risks that make his girlfriend Dorinda (Holly Hunter) and best friend/fellow pilot Al (John Goodman) nervous. It’s gotten so bad that Al strongly suggests Pete consider leaving the dangerous environment to train pilots in Colorado, and Dorinda threatens to leave Pete if he doesn’t slow down.

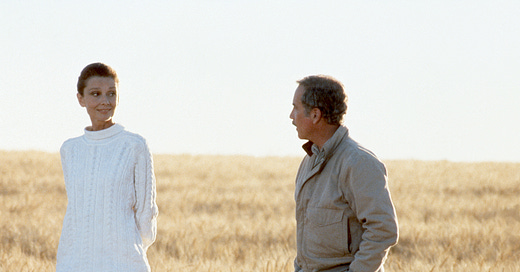

Pete promises Dorinda that he will take Al up on his offer. But the next day, there’s another blaze and, in an attempt to save his friend’s life, Pete crashes. He awakens in a burned-out forest, where he meets a friendly spirit named Hap (Audrey Hepburn, in her final role). Hap informs Pete — who takes the news very well — that he is dead, and must now serve as an inspiring spirit to another pilot, the handsome but none-too-bright Ted (Brad Johnson), who as you might expect, has developed feelings for Dorinda.

It’s the type of concept that, depending on the director, could be moving and inspirational or a cloying mess. The frustrating thing is, Spielberg should be the right person for this material. In his best moments, he’s capable of transcendence and wonder, and E.T. and Empire of the Sun showcased his ability to plumb emotional depths and wrest tears from audiences. Maybe he thought he was the perfect person, too; the director has stated that his biggest failures come when he’s overly confident, and here he seems on autopilot, despite his personal love for the source material.

You can correctly assume that he handles the moments of spectacle well. Spielberg has long had a fascination with World War II-era planes, likely stemming from hearing his father’s stories about the war. Empire of the Sun was almost fetishistic in its love for bombers of that era, and Always has several sequences where the director lovingly lingers on shots of restored fighter planes flying to combat a more modern foe. The scenes are energetic and refreshingly tactile when viewed in an age where CGI robs too many of these moments of suspense.

But when the film is grounded, which is quite a bit, Spielberg seems lost. He relocates the action from the 1940s to the late ‘80s, but his characters behave like they’re still in a WWII-era comedy. There’s a bizarre scene early on where Dorinda enters a dance hall wearing a dress Pete bought her and Spielberg’s way of showing how stunning she looks is to have every man behave in an overly choreographed manner as they try to dance with her; it feels more akin to something out of 1941 than a modern drama. The script is peppered with corny dialogue (when ghost Pete catches on that Ted has a crush on Dorinda, he says “hey fella, stay away from my girl”), and shifting the action from the war to firefighting only makes Pete’s recklessness seem more insufferable and pointless.

With a few exceptions (which I’ll get to in the next section), the cast does what they can with the material. Hunter is never less than wonderful, and she’s the strongest thing in this movie. Dorinda is the only character who doesn’t feel like she was pulled directly from an earlier era, and Hunter is funny and spunky while also being able to sell the heartbreak and confusion she feels as she begins to fall for another man. Her chemistry with Dreyfuss is cute. Likewise, John Goodman makes any movie better, and the film has a jolt of energy whenever Al’s on the screen, even if the film too often treats him as loud and obnoxious comic relief.

The film’s first half-hour, where the three go about their routines and relationships, is its strongest, the bizarre dance-hall scene serving as an exception. There’s the sense that these characters have a life together, and while Spielberg’s world-building is fine, there’s no urgency. Pete and Dorinda fight before his death, but that’s largely resolved; the only lingering thread to their relationship is that Pete never said “I love you.” Ted’s introduced before Pete’s death, but only through fleeting glances and stares; he falls so quickly for Dorinda without even saying a word that, when he reconnects with her later through a series of unfunny pratfalls, the film has already telegraphed where everything will head (and Ted is such a passive non-entity that the love story never feels believable anyway; his only defining characteristic is that he can do a bad John Wayne impression). Al simply exists in the back half of the film to connect the characters.

The film never has a clear direction of what the characters need, and it never seems in a hurry to find out, even if Pete’s been given some tossed-off warning about not wasting his spirit. When he arrives to inspire Ted, there’s never a clear goal and, indeed, Ted seems to find his way on his own and the film’s climax doesn’t even involve him. For a movie about last chances, regret and letting go, Always is strangely lackadaisical and unfocused, and any tension, suspense or romance deflates when Pete dies.

And that brings us to the most confusing thing about this movie: how Spielberg whiffs on the wonder.

It’s a Dull Afterlife

Steven Spielberg is one of our most emotional and creative filmmakers, and there’s a playfulness mingled with the wonder in many of his best films. Think of the dance with light and sound at the climax of Close Encounters or the humor that accompanies E.T.’s acclimation to the suburbs. He’s also a master at emotional catharsis. And so it’s curious that, when presented with an opportunity to indulge curiosity about the afterlife and musings on mortality, he delivers a film so pedestrian and lacking any urgency.

Part of this, I’m afraid, is Dreyfuss’ casting. Dreyfuss is an actor I enjoy in many roles, including several that he’s done with Spielberg. I love the smug wiseass he plays in Jaws and his childlike enthusiasm and wonders is a key part of what works so well in Close Encounters. And while the actor has some cute chemistry with Hunter early in Always, Pete is also a bit of a jackass. He’s a wiseass and a prankster, often at his friends’ expense. And while that might make him lovable, there’s an assholery to the way he talks to Dorinda about her lack of experience flying or forbids her from trying to take action on her own.

That wouldn’t be a problem if Pete’s afterlife arc was to stop being a jerk. But it’s not. His biggest joy in revisiting his friends as a ghost is watching Al be the butt of Ted’s pratfalls, and even in his climactic scene with Dorinda he’s smug and condescending before having a plot-motivated change of tone. He’s flippant and sarcastic, but also woefully un-urgent for a man trying to figure out what he needs to accomplish before he can pass on. When he learns he’s dead, he processes it for a half-second before being okay with it and letting Hap give him a haircut; when he learns that he has to inspire someone else, he accepts it with the same attitude as an intern being asked to get a coffee. There’s never a moment where he mourns the loss of his life and dreams, aside from some wistful stares at Dorinda. Even the one romantic interlude they get feels obligatory and rushed, the emotion of the moment coming from John Williams’ score.

And the idea of life after death is sadly under-realized, relegated solely to some surreal(ish) shots of a barber chair in the woods and Audrey Hepburn acting chipper, but not especially ethereal. There’s no sense of magic or wonder, things that should come naturally to Spielberg. And whatever Pete is supposed to accomplish before moving on to whatever comes next is unclear. He’s vaguely told he needs to inspire another person, which the film presents as Ted. But Pete doesn’t provide inspiration so much as instruction, the same thing the pilot could get from a half-decent flight school. He watches Ted and Dorinda fall in love, but isn’t responsible for much more than whispering some bland nothings so that she knows it’s okay to move on at the end; which would mean more if there was any passion or heat to the Ted and Dorinda relationship. Instead, he’s just a kind, dumb hunk who she develops a crush on shortly after meeting him, and they connect over bad impressions. There’s never much push and pull to Dorinda feeling like he’s a replacement for Pete, and Pete doesn’t really do much to interfere and try to stop the burgeoning romance and create some tension.

A recurring theme in Spielberg’s work concerns miscommunication. And that might be an interesting obstacle for Pete to have to overcome. After all, how does a spirit inspire someone they can’t talk with? Will he communicate through the plane’s radios, flickers of light, some other ethereal means? It turns out that there is no mystical solution; Pete just talks. Often, he yells, which the movie finds hilarious and I found obnoxious. Pete stands behind or beside someone and just…talks. As if he’s in the same room. They can’t see him, but the result is that there’s not much different than having an actual conversation. Even the film’s one attempt to broaden its scope, featuring a bus driver who dies on the road after a near collision, is unmoving and dull, with Pete just telling the man “you did a good job.”

Not only is it unimaginative, it’s undramatic and robs the film of any whimsy or mystery. It undercuts the idea that Pete is separated from anyone else, removing any sense of isolation or loneliness Spielberg tries to convey. Coupled with the film’s lack of urgency, it is also dreadfully dull and lifeless, a film that wants audiences to be moved and inspired simply because it’s this director telling us this story. But there’s nothing in the execution to move us.

The film’s climax is equally inert. There’s another disaster, which Ted is about to fly into. By this point, he’s accomplished himself as the best pilot Al’s ever seen; his arc is over without much help from Pete. So, wanting to avoid losing another love interest (even though they’ve had one date), Dorinda takes the controls and flies off on her own. Pete lambastes her again (which she can’t hear but can apparently feel) and then guides her through; he then makes a few comments that she is able to sense in her mind, and she lets him go. He walks off away from everyone else in the film’s final shot, with no dramatic heft or inspiration, more like a guy who just punched out after a shift at the factory.

Like I said, it’s not Spielberg’s worst film. The flight sequences are fun to watch and there are some brief moments of charm. But there’s also nothing memorable or engaging. Even his worst films have moments I return to — the dance/fight in 1941, the double T-Rex attack in The Lost World. But Always is just tedious and dull, a movie that, despite its love of planes, never achieves any emotional or dramatic liftoff.