Sundays with Spielberg: "Duel"

Kicking off a new series with a revisit of the beard's first work.

Okay, a bit of preamble. You caught me at vacation time. There was no newsletter last week because I was on a much-needed vacation in Florida with my family. We have a family wedding this weekend in Traverse City, so this week’s also been a bit of a blur. So, I haven’t had the chance to sit down and write a proper newsletter for a bit.

But there is stuff coming, I promise. Next week, I’m going to continue my Summer of 1996 revisit and tie it into a monthly feature I want to do. There are some podcasting projects in the works I’m excited about getting back to, including a new miniseries on We’re Watching Here, a rebrand of Cross.Culture.Critic., and a new project I’m having a lot of fun with. All that, and I’m waiting for the go-ahead to announce a new writing project that is kind of a new direction for me.

This is all, of course, on top of a full-time job and responsibilities at home. And one thing that I think is going to take a hit as I attempt to balance all of that is reviewing new releases. It’s something I’ve enjoyed for the last 15 years, but the truth is I don’t really get excited when I think about that anymore. It’s a grind, and I’ve found much more fulfillment writing about only the movies I want to write about, whether that’s a new release or something older. And so I think this newsletter will be my main focus for writing about films.

One thing I started last year was an attempt to get through the filmography of Steven Spielberg. I stopped right after The Color Purple, but always intended to pick that up again. And this is a good time to do that. So, we’re going to do that — not as a replacement to the weekly newsletter, but as an addition. Every Sunday, I’ll have an essay on a Spielberg film, hopefully ending right around the same time that his West Side Story remake hits theaters.

Here’s the disclosure: Because I started this just last year, the first few of these will largely be republications of pieces I previously wrote (although I might tweak some, and I’m considering whether to rewrite my piece on Jaws, which is tied closely to the pandemic). So, if the first several feel a bit familiar, that’s why. But it’s all still free right now. I may switch it to a paid feature after the Color Purple piece, but I’m still deciding (the main newsletter will remain free for the foreseeable future). We’ll see how this goes.

So, buckle up — we’re starting today, and we’re starting with Duel.

Start your engines

I’ll admit there was some debate about where to start this. Spielberg’s first film made explicitly for theatrical release was 1974’s The Sugarland Express. Prior to that, the director had spent time in television, helming episodes of Night Gallery, Marcus Welby, M.D., and Columbo. Prior to Sugarland, he did three television movies, including two in 1972 (Something Evil and Savage). But it’s a film he did one year prior, the ABC television movie Duel, that is widely acknowledged as his first feature, mainly because it received a brief theatrical release in the United States and Europe.

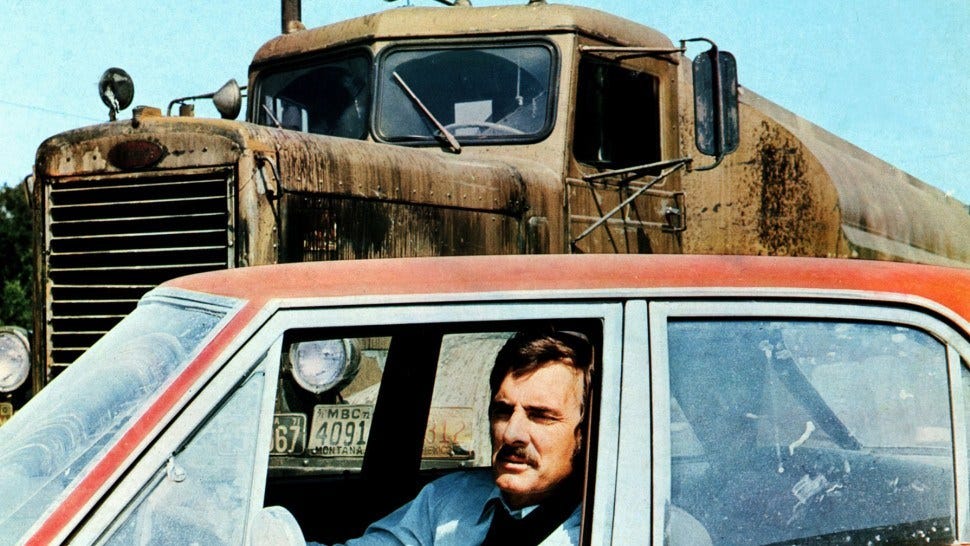

A man-versus-machine thriller based on a short story by Richard Matheson, Duel stars Dennis Weaver as a mild-mannered businessman whose day is ruined when a sadistic semi truck driver begins stalking him. What starts as an aggressive show of road rage soon becomes something more dangerous as the two engage in a dangerous battle across dusty California roadways.

Spielberg’s filmmaking skills are muscular from the start, with the young director already showing a knack for visual storytelling. Many of the director’s hallmarks, including closeups and a fondness for capturing eyes in rear-view mirrors, are already on display. Once the film hits the open road, it rarely lets up, and Spielberg finds unique ways to build tension in the cat-and-mouse game between a Plymouth Valiant and a hulking semi.

With Duel, Spielberg gives himself a land-locked dry run for Jaws. While much of that film’s legend is supplied by Spielberg creating tension out of necessity, the truth is that Duel proves that his instincts for crafting suspense were in place well before he went to sea. He understands how to ramp up the tension, knowing just when to bring that semi back into view and when to go full-throttle. As with Jaws, there’s an unseen threat; we never get a glimpse of the truck driver, although the rusty behemoth constantly fills the frame. The chase sequences are often white-knuckle and intense, at at least one image — the semi barreling toward a phone booth — elicited a gasp from me.

Anchoring the story is Weaver, the only face we spend the majority of time with. He brings a wiry, anxious energy to the story, starting as a braying nerd who belongs in a city, not in the wilds of the desert, and turns into a man whose survival instincts kick in. It’s a solid performance, with Weaver’s reedy voice a constant reminder that his character’s out of his element.

Mann versus machine

Spielberg has never been our most subtle director, but in Duel the subtext constantly becomes text. Duel is a film about masculinity, going so far as to give Weaver’s character the surname Mann. He listens to the talk radio on his drive out and the stories are peppered with men making jokes about not being the man of the house and dealing with their anxiety over being displaced by strong women. During a phone call with his wife, Mann apologizes for not defending her. His shiny red Plymouth looks impotent and week next to the bulging, smoke-belching semi (there’s a great shot where the two are parked side by side at a gas station and Spielberg pulls out to let the truck dwarf everything around it).

When Mann enters a café for refuge, his polyester suit and groomed mustache are out of place against the worn boots and tall hats of those sitting at the bar. His attempts to smooth over the situation with a man he believes to be the truck driver belie that he’s a person who has never willingly entered into any confrontation. By the end of the film, he’s the one goading the driver into a fatal game of chicken.

As on the nose as these choices are, they add a primal pull to Duel that makes the stakes feel higher and the story more mythic. It’s a battle for supremacy between man and machine, but that machine is just as much beast as mechanics (when the truck falls to its eventual demise, Spielberg uses the roar of the monster from Creature from the Black Lagoon, which he would also re-use when the great white is vanquished at the end of Jaws). Spielberg takes a simple story of road rage and transforms it into a parable of emasculation and the mechanizing of culture.

It’s not without its rookie bumps. In several instances, Spielberg uses voice over to get us inside Mann’s head, but the dialogue feels stilted and out of place. Weaver’s performance and Spielberg’s visual storytelling prowess easily work to imply the mental fragility Mann falls into, but the voice over is distracting and redundant. It takes us out of the story’s primal pull. The film’s final moments also feel rushed and abrupt. After a thrilling hour and a half, Mann’s victory seems too easy, and his triumphant laughter at the end undercuts his transformation. Rather than being shaken by his ordeal and what it’s forced him to become, he seems excited and energized, the wrong note for the moment.

Yet those are minor quibbles, and Duel still retains is power nearly 50 years after its release. It shows Spielberg’s skill and storytelling strengths, which he would use to perfection four years later in Jaws. But first, he’d take to the open road once more with The Sugarland Express, which we’ll revisit next week.