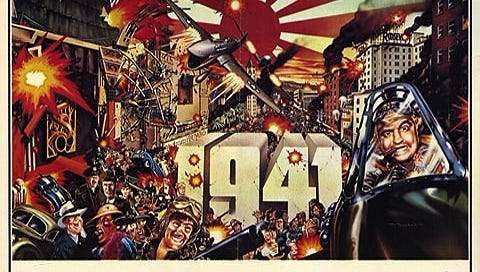

Sundays with Spielberg: There's no Indiana Jones without '1941'

Looking at one of Spielberg's worst and one of his very best.

Last week saw the 40th anniversary of Raiders of the Lost Ark, not just one of Steven Spielberg’s best films, not just one of the greatest movies ever made, but, on any given day, my all-time favorite movie. I couldn’t wait to get to it. There was just one problem.

1941.

The film has a reputation as one of Spielberg’s worst; it’s valid. While the director would go on to have more egregious stinkers throughout his career, 1941 is generally agreed to be a bad fit for him.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind had exhausted Spielberg, and he hoped the screenplay by Bob Gale and Robert Zemeckis would cheer him up. Even though he derisively described reading it as similar to scrolling through an issue of “MAD Magazine,” he liked the idea of making a sprawling, big-budget comedy, but also told The New York Times that throughout production, he kept thinking “this is not a Steven Spielberg movie.”

And it’s not. 1941 is a messy, loud farce. Impressively detailed and gorgeously shot, it’s also populated by horny dimwits. The jokes are on par with a second grader kicking someone in the crotch and staring up girls’ skirts; every joke is either a sex gag or an explosion. Spielberg mentioned the “MAD” vibe, and it’s true; watching 1941 feels like reading one of the magazine’s impeccably drawn movie parodies, but with an added feature that, this time, the magazine screams in your ear.

Raiders, on the other hand, provides a conundrum. What can I say about it that hasn’t been said before? Watching it in such close proximity to 1941, I also wondered how a director who’d made such a sprawling, aimless mess could rebound so quickly with something so focused and assured. Raiders is Spielberg’s third masterpiece before age 40, and a perfect piece of entertainment. And the more I thought about it, the more I realized it likely was only due to the bruising he received from his WWII bomb.

Spielberg learned lessons from the failure of 1941 that allowed him to turn Raiders of the Lost Ark into the classic we love today. 1941 is a mess; but without it, we might not have Indiana Jones.

It’s the story (economy), stupid

Gale and Zemeckis would ultimately deliver their own piece of blockbuster perfection with their script for Back to the Future. That script is a piece of beautiful clockwork, in which every line of dialogue sets up something that’s paid off shortly after. It’s funny, clever and it works like a charm.

1941’s script is…not that. Taking place over several days in Los Angeles in December 1941, the film observes the paranoia that gripped the coast following the attack on Pearl Harbor. As Christmas approaches, Californians are panicked that another attack is imminent. And that, apparently, makes them very horny.

Nearly half of the film’s story concerns people trying to get laid or trying to stop other people from getting laid. Its core romance, between civilian Wally (Bobby Di Cicco) and his girlfriend Betty (Dianne Kay), largely just concerns Wally trying to stop aggressive Corporal Sitarsky from having his way with her after a dance. It’s just as gross as it sounds; the back 30 minutes of the movie turn into an extensive chase scene where the objective is for Betty not to be raped. Meanwhile, Tim Matheson plays a bumbling Army captain whose sole desire is to get an ex (Nancy Allen) into an airplane because it’s the only place she can be sexually satisfied.

This was, of course, the age of Animal House, and Spielberg even pulls Matheson and John Belushi in to his sex farce. But where Animal House and Caddyshack reveled in their rudeness and presented it as an act of rebellious raucousness, Spielberg’s too square to make the sex jokes feel anything other than juvenile. We can get to whether any of it is funny (it’s not), but it also weighs down a film that features lengthy plots involving Lorraine Gary and Ned Beatty as homeowners gifted a weapon to help defend the coast, Murray Hamilton and Eddie Deezen (and a ventriloquist dummy) as nitwits guarding California from a Ferris wheel, Robert Stack as a Dumbo-loving general who might be the only sane man in the Army, Dan Aykroyd and John Candy as privates preparing for an invasion, Belushi as a crazed pilot who stammers around and drinks, and (checks notes) a subplot where film icon Toshiro Mifune tries makes Slim Pickens poop out state secrets.

That’s a lot of plot, even if you choose to go with the 150-minute director’s cut (which is better than the theatrical, but not enough to recommend). For a director who was more fleet-footed and suited to farce, the combination of paranoia, pent-up passion and war mongering could conceivably build momentum and turn into something fun. But Spielberg is too sincere for the ironic distance required; he doesn’t have a grasp on this mode of storytelling. Multiple storylines vie for attention, but none of the characters are believably human or remotely likable. Spielberg never quite turns it into a spoof, but also never grants his characters a soul. Instead, the film is just an ever-growing ball of giant set pieces, slapstick antics, explosions and sex jokes that add up to nothing because there’s no one in the center for the audience to identity with during the ride.

Rebounding with ‘Raiders’

1941 came in over budget and over schedule, a then-common occurrence for Spielberg. When he committed to direct Raiders of the Lost Ark, based on an idea from his buddy George Lucas, Spielberg was determined to prove that he could deliver a movie on-time and under budget. Raiders is a lean production, shot rapidly and relatively cheap. And that leanness applies to Lawrence Kasdan’s screenplay. It’s not a sprawling story; the focus is squarely on Indiana Jones and his quest to retrieve the Ark of the Covenant. Aside from a few instances featuring Marion, we don’t leave Indy’s side through the entire movie.

Kasdan’s script is meticulous. Every sentence pushes the story along. We don’t delve too deep into a background for Indy or Marion; we get a few lines that allow us to flesh out their personal stories, and the chemistry between Harrison Ford and Karen Allen fills in the rest. There are no flashbacks to the Ark in action, no elaborate mythology to put together, no parallel sequences of the Army’s own quest to track down the Ark, all of which would be thought absolutely essential for a studio making this movie today.

Raiders’ roots lie in the serials Spielberg and Lucas watched as kids, and in the director’s thwarted desires to make a James Bond movie. It takes the best parts of those movies — the thrilling chase scenes, the intrepid hero and feisty love interest, the dastardly villains — and then gooses them with sharp dialogue, fantastic performances and clever direction. John Williams’ iconic score does a lot of the heavy lifting in widening the scope. It’s a movie where the lead couple’s relationship is explained in one line and a scene of simple exposition early on sets up the film’s supernatural finale.

Both films have their commonalities. They are period pieces, rooted in a love of nostalgia and movies, with Raiders pulling from cliffhangers and serials and 1941 leaning hard into Spielberg’s love of Americana. They feature World War II villains as enemies; despite the presence of Mifune, 1941’s Japanese sailors never feel like much of a threat, mainly because Spielberg spends so much time treating them as bumbling, ill-equipped fools (which might work if it were funny). Raiders’ Nazis are just as cartoonish, just in a different way. They are unredeemable and evil, monsters who we can’t wait to see Indy punch out. Spielberg doesn’t need sequences of them bumbling around making poop jokes; a swastika and machine gun set them up as enemies. The main villain, Paul Freeman’s Belloq, is also never explained away; he thwarts Indy early on, makes a comment about how the two of them are alike, and then tries to get Indy’s girl. A few quick scenes, and he’s an iconic bad guy (Freeman’s delicious performance helps). Raiders gets in and out in just under two hours, while the full story of 1941 feels crammed and overstuffed even in the lengthy directors cut. This is a case where less is absolutely more.

Indiana Jones and the expert pace

The big knock against 1941 is that it has no pacing, leaping from one “wacky” set piece to the next without catching its breath. As Ebert said in his review: “It’s not fair to say Steven Spielberg’s 1941 lacks ‘pacing.’ It’s got it, all right, but all at the same pace: The movie relentlessly throws gags at us until we’re dizzy.”

The film’s plot threads don’t flow into each other or build momentum; they run into each other, land on top of each other and crowd the screen as Spielberg hopes the frenetic pace will build laughs. It rushes headlong into its sex jokes and slapstick, never stopping to let its characters establish themselves or create any stakes. The best comedies, yes even sex comedies, work because there’s a core humanity. Farces work because there’s a momentum and precision. 1941 opens with urgency and continues with urgency without telling us why it’s being so urgent. Every moment is filled with “gags,” opening with Wally trying to do complicated dance moves while he washes dishes and continuing through to the film’s climax, when Belushi chases Matheson and Allen through the skies over Los Angeles. None of it matters, because the film isn’t interested in making us care; it thinks it’s making us laugh, but hasn’t done the emotional legwork.

It doesn’t only play at one speed; 1941 also only has one volume. Everything in the movie is loud and broad. Ned Beatty opens the film as a bumbling oaf and ends it by blowing his home off a cliff. Belushi chews the scenery as if this was a lengthy SNL sketch from. The dialogue is vulgar instead of clever, and noise replaces wit. Spielberg indulges his worst instincts to create big set pieces where the joke is just that they’re big setpieces. A Ferris wheel crashes into the ocean, a house falls into the sea, there’s a meticulous re-creation of the opening of Jaws that only exists to deliver an upskirt joke as a punchline. It all looks fantastic, and it all gives me a headache.

Raiders, in contrast, is perfectly paced. Every individual action sequence is like a short film, with its own rhythm and tone. In an age where all action sequences are CGI assaults of light and noise, it’s refreshing to watch that cold open where Indy goes after the idol, Spielberg slowly ramping up the tension until that boulder comes crashing down. The fight in the marketplace has its own ebbs and flows, moving easily from one setting to another, tossing in a chase sequence, a fist fight and Indy’s classic shooting of the swordsman. It flows from a brutal fistfight outside the Flying Fortress into one of the all-time great chase sequences while making both scenes feel unique and of a piece. By the time we reach its climax, the film has given us enough unbelievable moments and epic escapes that it’s only logical to believe the supernatural entrance in what had before been a seemingly unspiritual film.

[[A side note: I recently showed this film to my son for the first time. He’s 9, and he’s had a steady diet of Marvel movies and Star Wars, so I figured he’d be ready. Throughout the film, he was engaged in all the fist fights and chases, but I was curious how he would react to the horror movie finale. When that ghost came up and Toht screamed, Mickey laughed. Then the faces started melting. In quick succession, I heard a gasp, felt him briefly burrow his head into my arm and then he started cackling. This movie flat-out plays.]]

For as fast as Raiders moves, it’s never exhausting. Spielberg, working with editor Michael Kahn (who also edited 1941), expertly shifts gears. The movie knows when to let the audience breathe and deliver exposition, build stakes or let the chemistry flow. It stops just long enough for us to understand Marion’s life before Indy returns to it, watch the hero mourn when he thinks Marion is dead, and give Indy and Belloq a brief chance to trash talk each other before moving on to the next spectacle. It’s a movie that moves but also knows when to dial down the speed, something Spielberg wouldn’t always do as well with the Indiana Jones sequels.

Spielberg and comedy

For some, the lesson of 1941 was that Spielberg shouldn’t do comedy. And even the director seemingly took that to heart; aside from arguably The Terminal in 2004, the director has never again ventured straight into comedy (and even “The Terminal” walks a wavy line between comedy and drama).

But the truth is, the notion of Spielberg as an unfunny director was dispelled with Raiders, which is one of his most visually playful and witty films. Spielberg’s direction in the Indiana Jones movies is constantly funny; as dark as Raiders can get, there’s always a gag nearby to let out some tension. Early on, as he’s trying to escape the temple with the idol, there’s a moment where Indy leaps across a chasm and grabs onto a vine. He smiles in relief, and then a second later, the vine starts to rip from the wall.

It’s a perfectly executed gag, directed with precision timing by Spielberg and delivered wonderfully by Harrison Ford. It’s a laugh moment in the midst of the chaos, and it informs the character, who, unlike James Bond, doesn’t always remain calm in the face of danger. Ford is great at creating an adventurer who’s intrepid but also a bit of a fool, and his collaboration with Spielberg results in some great comedy. Think of the aforementioned ending to the fight between Indy and the swordsman. It’s a wonderful gag, and famously one that wasn’t in the script. In the documentary that accompanied the film’s DVD release, Spielberg explains that Ford was suffering from a stomach bug and, instead of trying the arduous stunt sequence again, just suggested ending the moment with a gunshot. It’s one of the movie’s most memorable moments.

But Spielberg’s humor is apparent even without his lead — and had been throughout his career. Jaws isn’t exactly a hoot, but Spielberg gets some laughs with scenes of an old man in a washcap being mistaken for a shark, Hooper’s attempts to look macho in front of Quint, and a few well-timed reaction shots. The alien spaceships in Close Encounters are first introduced to Roy in a gag involving headlights in the rearview mirror. And Raiders is filled with some of Spielberg’s best visual humor, whether it’s a patron at Marion’s bar toppling over drunk, Sallah dropping the Nazi flag down to help Indy climb out of the hole after soldiers steal his rope, the monkey who can give the heil sign, and the great look on Ford’s face when a terrified Indy comes face to face with snakes. One of the film’s best gags, when Toht reveals what is thought to be a torture device that turns out to be a coat hanger, was actually intended for 1941.

So why does that humor work in Raiders and not 1941?

In Raiders, the humor is usually delivered as a grace note. Spielberg is an emotional director, and he knows the value of letting the audience relax. He also knows that a film as over the top as Raiders needs humor to help the audience suspend disbelief. The jokes help shade in the characters, create the film’s tone and goose the action. By not being the driving force of the movie, the humor both works better and elevates the film.

But 1941 is all jokes. There’s no break from them. And Spielberg, at that point in his career, was much more skilled with a visual gag than a verbal joke (see Lincoln and Bridge of Spies for proof of how much better he’s gotten with that). Zemeckis and Gale’s script is puerile and crass, and Spielberg is simply too much of a nerd to make it work. Particularly in the early going, most of the film’s laugh moments are centered around sex gags, innuendo and insults, and the director just isn’t able to make them work.

Later in the film, there are several set pieces where Spielberg does coax a laugh. Robert Stack’s captain tearfully watching Dumbo gets a chuckle, and there’s a dance sequence that turns into a brawl that has long made me eager for what Spielberg could do with a full-on musical. The Ferris wheel sequence is an astonishing work of special effects, but also just a funny image. But because everything in the movie plays at that one pitch, the jokes don’t have punchlines; they just flow into the next joke. And it’s wearying rather than funny.

1941 has funny moments, but I hadn’t thought of them at all in the decade since I last saw the film. Conversely, Raiders’ moments, both funny and exciting, are burned into my memory. And the laughs work better because they largely come in unexpected moments, twisting sequences that initially appear to play completely serious. It’s a funny movie, and its humor is why it’s such a delight to watch over and again.

When 1941 is discussed, it’s largely done so in the context of it being one of Spielberg’s rare early films to whiff. It’s gained a bit of a cult following, but even its defenders are largely of the “it’s not that bad” variety. It’s not his absolute worst film, but it’s a mess, and a bad fit for a director whose career has been modeled on sincerity and emotion. But it was a mess Spielberg had to get out of his system, and Raiders is a lean, focused response.

But his biggest box office success — and another masterpiece — was right around the corner.

Previous Sundays with Spielberg entries: