'The Truman Show,' freedom and less-wild lovers

Looking back at Peter Weir's masterpiece nearly a quarter of a century later

One of my favorite films, Peter Weir’s The Truman Show, turns 25 in June. In honor of that anniversary, I was going to republish this piece — which I wrote years back and is one I’m particularly fond of — closer to that date. But life’s been busy this week and I’m entering a crunch of a holiday weekend and the last month of a grad certificate class, and didn’t have much time to dedicate to crafting an article. Plus, being that it’s Holy Week, I wanted to write about a movie that has affected me on a spiritual level. So, I thought I’d bump this up now — it will give you plenty of time to watch it before Truman turns 25 this summer. I hope you enjoy this piece.

In their 1997 book The Sacred Romance, Brent Curtis and John Eldredge1 discuss the rut that many people often find themselves in. Yearning for lives of adventure and romance but finding that those very things require risk, many settle for what the authors call “less-wild lovers” — distractions that temporarily pacify desire without requiring too much.

There are two forms these “lovers” often take. The first is addiction — drugs, pornography, materialism — that give the rush you’re looking for without asking for commitment, risk or vulnerability.The second, and probably most common, is that of a comfortable, safe and ordered life. We close our hearts, isolate ourselves from meaningful relationships, insulate ourselves from danger and keep busy. We settle for secure jobs, functional relationships and checklist-oriented religion to bury that yearning and anesthetize our heart.

But the heart doesn’t stay quiet. It nags like none other. That’s why, deep into middle age, we can be sitting around in our comfortable suburban life and feel a twinge of discontent, a quiet panic at the back of our minds asking: is this all there is?

This thought comes to mind whenever I watch Peter Weir’s The Truman Show. There’s a lot to dig into in this movie. You could focus on Jim Carrey’s nuanced performance or the film’s critique of the then-fledgling medium of reality TV. But what strikes me most is The Truman Show’s existential dilemma — the story of a man whose heart is waking up, telling him to run away from everything that’s kept it quiet. The difference between Truman and us is that we’ve chosen our less-wild lovers, while his have been forced upon him. But they certainly work hard to woo us.

Lifelong vacation

Located on Florida’s Gulf Coast between Panama City Beach and Pensacola lies a scenic stretch of highway. It’s a favorite vacation destination for my family; in fact, I’ll be there in about a month. On the outskirts of the tacky tourist traps and away from the Hard Rock Cafes, Margaritavilles and crowded public beaches, this winding stretch of coastal road is home to several resort towns featuring quaint shops, unique restaurants and beachfront views. With its beautiful picket fences, pastel homes and quaint walking paths, I’ll often visit several times in one trip. I can spend hours browsing its bookstores, walking its streets, or kicking off my shoes and running to the beach.

The town, Seaside, was an ideal location for Weir to film The Truman Show. The film takes place in the fake city of Sea Haven, constructed in a massive dome just outside of Hollywood. Truman Burbank (Jim Carrey), a child adopted to star in a reality TV show, has grown up believing it’s all real. The first step to making sure he never thinks about leaving? Place him in a town where packing your bags would be the last thing on your mind.

Seaside’s re-creation of an idealized small-town America is nearly too perfect. It’s quiet, safe and expensive without being pretentious. The area has an average of 320 days of sunshine each year. If I wanted to create a town no one would ever leave, I would build Seaside. When I’m there, I dream of convincing my wife to quit our jobs and open a burger shack on the beach, far from the bills, responsibilities and cold weather of Michigan.

Truman is not, technically, on vacation — he still has to go to work, tend the lawn, etc. But his life is designed like one, organized and planned out so that he’ll never think of leaving his sunny, pastel home. The challenges he faces in every day/episode have been thought out by writers and carried out by actors. Everyone greets him warmly, and he returns in kind with his trademark “good afternoon, good evening and goodnight.” Truman’s best friend shows up with a six-pack at just the right time and his wife Meryl (Laura Linney) is always ready with a smile and a hot meal. Constant product placement reminds him just how great all of his stuff is, and if things get frustrating, he can just go buy a new lawnmower.

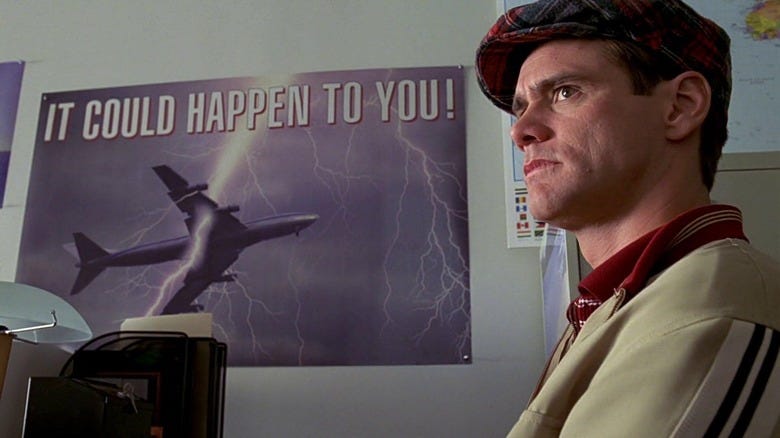

Why would he ever want to leave? It’s safe. It’s sunny. It’s predictable. The newspapers trumpet stories about Sea Haven’s greatness. Television programs reinforce the joys of small-town living and familial proximity. The local travel agency actually discourages traveling — in a clever visual gag, the office has a poster of an airplane being struck by lightning. The radio announcer cheerfully asks Truman whether he plans on making any trips, and the bus drivers and ferry operators don’t even know how to work their vehicles.There’s no real risk in Sea Haven, no danger to Truman’s life — even his biggest fear been manufactured to keep him from venturing too far. And if Truman starts thinking about leaving, his friends are there to coax him back down — with some help from the writers, of course.

Because it’s not real. It’s not free.

It’s the Matrix.

I’ve seen The Truman Show close to a dozen times, but it’s only recently that I’ve noticed similarities to the Wachowski’s sci-fi epic, which would come out the following year. In The Matrix, Neo learns that what he assumed was the real world was actually a complex computer simulation designed to keep humans comatose while they provided power for machines. The film’s bleak, grimy and gray — the tonal antithesis of the colorful Truman Show. But doesn’t Sea Haven exist for the same reason: To turn Truman into a power source for a corporation? Isn’t he kept pacified so that he can draw ratings and help companies sell their products?

Granted, in The Matrix, every human is enslaved to the machines. In “The Truman Show,” only one resident of Sea Haven is unaware of what’s going on. But the program’s insidiousness is missional, ensnaring people outside of the dome, far away from Sea Haven’s beaches.

Several times throughout, Weir cuts to the people watching “The Truman Show.” There are entire bars formed around the program where people gather to binge (drinking and viewing) together. Two women watch while knitting a Truman quilt. One man appears to never leave his bathtub, where he has a TV set up. The show’s creator, Cristof (Ed Harris), boasts that some people keep the show on while they sleep.

People are ensnared by the show. It becomes the source of their social lives — or their reason for a lack of one. It’s a political cause for others to rally behind. Those with real problems can get lost in the assurance that, no matter what happens to them, Truman will still tell his neighbors “good afternoon, good evening and good night.” Loneliness isn’t a problem when you can spend all evening watching someone else’s life unfold. And if you’re bummed that your life doesn’t look like Truman’s — well, there’s always the Truman Show catalog, where you can order all the products and clothes worn on the program.

Entertainment and advertising pacify Truman — particularly that part of him that wants to break free. The show’s creators weave a narrative that tells him that the good life is found close to home; only danger exists outside. That same industry tells viewers what a “good life” looks like — a nice home in a cheery suburb, with a wife who will remind you to keep upgrading to the best stuff. It’s the same tactic we see in our cultures — buy this, move here and pursue this in order to keep ourselves busy and drown out that voice that tells us there’s more. We don’t ask questions — we assume it’s normal. “We accept the reality with which we’re presented,” Christof says — and it’s just as true for us as it is for Truman.

But like I said, the heart nags, and forces beyond our understanding conspire to wake us up. For Truman, reality is about to come crashing in.

Reality (TV) intrudes

It’s a crash from heaven that rouses Truman from his stupor. One morning, as he gets ready to head to work, a light from the top of the dome falls to the ground and shatters at his feet. The producers hop into action, prompting the radio deejays to concoct a story about parts falling from airplanes.

But that one innocuous chip at reality is all it takes for Truman to begin asking questions. We quickly see that for all the cheeriness surrounding him, he knows something’s missing. The mysterious woman who briefly stole his heart in high school (Natascha McElhone) has never been far from his thoughts — Truman is piecing together a collage to recreate her face, and he makes calls to “Fiji” — where he believes she lives — hoping to track her down. He’s already suspected something was off — this new incident confirms it.

What’s more, the break in Truman’s carefully constructed world is followed by a reminder of past trauma, as Truman’s father unexpectedly crashes the set. Yes, his reappearance first calls to mind the tragedy that fueled Truman’s fear of the water. But it also increases the volume of that nagging voice in Truman’s heart. Spurred on by cracks in the world, Truman begins to see that things aren’t as they seem. There’s an elevator that opens into a catering area for the actors. The photo of Meryl crossing her fingers at their wedding. The commands to the actors that Truman’s car radio picks up. In one of my favorite scenes, Truman — beginning to pick up that everything revolves around him — gets out of his car to direct traffic. Something’s not right with the world and it fascinates Truman, jarring something loose that had been long dormant.

And while everything is still bright on the surface, we begin to detect sinister undertones. Weir, often adopting the POV of the millions of cameras around Sea Haven, never drops the bright facade, but it feels chillier. Laura Linney, so fantastic here, turns Meryl’s smiles into something hollow and cold — we begin to see her less as a friend and more as a captor. The look of Sea Haven, so beautiful and colorful, begins to feel plastic the more Truman realizes what a fabrication it is.

This is what happens when our hearts wake up and we see just how carefully constructed this system is. About 10 years ago, I was driving when I suddenly took note of just how many fast food franchises littered a one-mile stretch of road. I’d driven that way every day since I’d had my license and just accepted the Burger King, Tubby’s, Rally’s, Taco Bill and Arby’s as normal. Out of the blue, it occurred to me just how weird it is to live in a world with this much stuff thrown at us while people starve on the other side of the globe. It sickened me. It’s the same feeling I get these days when I take note of the thousands of ads that hit us each day,, with companies telling us what we need to make us happy, or when I hear people talk about what we need to acquire to live “the good life.” It’s all a system. It’s all broken. It’s all false. And if you look hard enough, you can see the strings being pulled to keep us content, predictable consumers who stay in line.

The mania of waking up

Of course, what happens when we act on this? When we decide that the system that currently has us all in its grasp is broken? When we listen to that nagging in our hearts and begin to pursue something more? When we go off the beaten path, abandon what everyone sees as “normal” and start to live from our passions?

We look crazy.

I remember talking with a friend shortly after The Truman Show was released about how much I loved Jim Carrey’s performance. My friend admitted that it was a good performance, but she wasn’t as impressed. “It’s just an everyman role,” she told me. “Anyone could do that.”

The more the film ages, the more I’m convinced she was wrong. Carrey is perfect for this role, which I think is the best performance of his career. Yes, he can play the everyman. But it’s that slightly “off” part of Truman’s personality that Carrey sells so well. Truman’s not a normal guy. Sure, he has a typical job and a life in the suburbs. But he talks like a 1950s television character. He plays out elaborate fantasies in the bathroom mirror. But while it’s all an exaggeration, audiences at that time would have seen it as a toned-down version of Carrey’s shtick — which found himself talking out of his butt cheeks in Ace Ventura and screaming like a buffoon in Dumb and Dumber. It’s both exaggerated and reined in…and creates a character who feels real, but just slightly off.

As Truman uncovers more about what’s going on, Carrey indulges a bit more of that manic persona. One scene finds Truman sitting in his car with Meryl, telling her about the routines he’s discovered surrounding him. It’s the scene where we’d normally expect to find the wild-eye protagonist piecing together his conspiracy, and it’s the one moment where Carrey is allowed to indulge his larger-than-life tics. Truman explodes into unpredictability, driving his car at a whim down different streets to find their paths blocked. And while the producers keep trying to stop him, Truman keeps pushing forward, even overcoming his fear of driving across bridges and venturing far enough that they have to stage a radiation incident just to keep him in line.

His unpredictability is exactly the type of thing the show's trying to prevent. And for Meryl, who’s been so good at keeping him in line over the years, it’s terrifying. After an intense encounter back at the home, she suddenly breaks character, shouting for the producers to do something. “I can’t work under these conditions. It’s not professional!”.

And like that, Truman’s reality finally shatters.

Carrey is key to pulling this off. There’s a dangerous comedic energy that the actor had early in his career where we’d show up in theaters just to see what he’d do next. Even as a teenager, I knew the Ace Ventura films weren’t good, but I watched them because of the way Carrey threw himself into his work, even if that involved being birthed from a fake rhino. It’s that mania that terrifies his handlers, believing that his unpredictability could truly be a danger. But because we know what Truman knows — actually, we know much more — we also know that this isn’t really insanity at all. It’s the heart coming to life, passion spilling out after years of being smothered. Carrey’s comedic instincts keep Truman unpredictable, but his dramatic skills keep him grounded so that we’re not just watching a performance; we’re watching a character come alive — perhaps for the first time.

Anyone who’s ever felt jolted into alertness when long-buried passions can understand what’s happening. When we see how false our world is and how unsatisfying these lovers are, and feel that desire begin to burst back to the surface, we feel crazy. We feel unpredictable. We feel dangerous.

And that scares everyone else.

The insidiousness of safety

Love him. Protect him.

That phrase appears on the shirts of “Truman Show” cast members. The entire defense given to why the show’s producers conduct the program and imprison a human being is that they’re protecting him from a harsh world. When a protester objects to what Christof is doing, calling it “sick,” the creator lashes out:

I have given Truman the chance to lead a normal life. The world, the place you live in…is the sick place.

Why do we stifle our hearts? Why do we cling to less-wild lovers who pacify us with busyness, functionality and distractions? Why do we settle for comfortable living, insulating ourselves with stuff instead of pursuing our passions? Why, when Truman declares “I’m being spontaneous” does a part of us concede that perhaps he needs serious help?

Because to live unpredictably can hurt. Risk taking is, by definition, unsafe. Passion doesn’t shield us from wounds — our own experience has told us that it causes them. In The Sacred Romance, Curtis and Eldredge discuss the moments when our childlike idealism turns into cynicism and distrust, likening them to arrows that have unexpectedly lodged themselves in our psyche, each one delivering a message — often false — about our identities. Those are the messages that tell us we’re not good enough, we can’t cut it, we’re unworthy of love. And so, wounded by life and fearing another arrow to our hearts, we retreat. Creativity gets replaced with menial work. Intimacy is replaced by functional relationships where people bite their tongues and risk offending. Adventure is replaced by comfort, our desire to explore quenched by the way we insulate ourselves with stuff. Faith — that once bright, burning passion in our souls — is replaced by religion where we try to maintain our place on a certain grid and check off our good deeds on a chart.

We cling to our lovers because we’ve been wounded — because we’ve tried to live free and been harmed. Truman, on the other hand, has always been surrounded by things that pacify his curiosity and stifle his desire. He’s in a world constructed to keep him predictable, passionless and tame. He’s been born into it — we run to it.

But so much of our retreat is prompted by the same promises that keep Truman in line. Our advertising is centered around the concept that buying a certain product or living a certain lifestyle will increase our confidence, inspire our friends to stick around, and help us obtain a life of comfort and security. True, we chose this world — but it was constructed and waiting for us.

Anyone who’s accomplished anything knows safety is overrated. We all die in the end anyway — the question we have to face is whether it’s a slow death, suffocated by comfort and distraction, or a noble one on the field of desire. Those who have loved greatly, composed great works or changed the world know security is one of the first things you have to sacrifice to accomplish anything. It’s not so much that we make a conscious decision to take the risk — it’s that our hearts propel us into it, throwing caution to the wind to achieve our dreams and become who we were meant to be.

The final minutes of The Truman Show are deeply moving. No matter how many times I’ve seen the film, I’m left with a lump in my throat. Truman, knowing that the world he’s grown up in is a trap, rushes headlong to find the truth. He commandeers a boat and heads out on the ocean. First trying to control him and push him back, Christof has the crew ramp up the storms. When Truman continues to press on, Christof decides that if he can’t control his “son,” he’ll drown him. But Truman keeps going, sailing to what is literally the end of his world. And when his boat crashes into a wall, Truman’s desire keeps driving him forward, beating it with his fists until Christof addresses him directly. He can’t control him. He can’t kill him. But he can appeal to his sense of self-preservation one last time, telling him:

Truman, there’s no more truth out there than in the world I created for you — the same lies and deceit. But in my world, you have nothing to fear.

Truman decides to live with the risk. He utters his catchphrase, takes a bow and walks right into a new world.

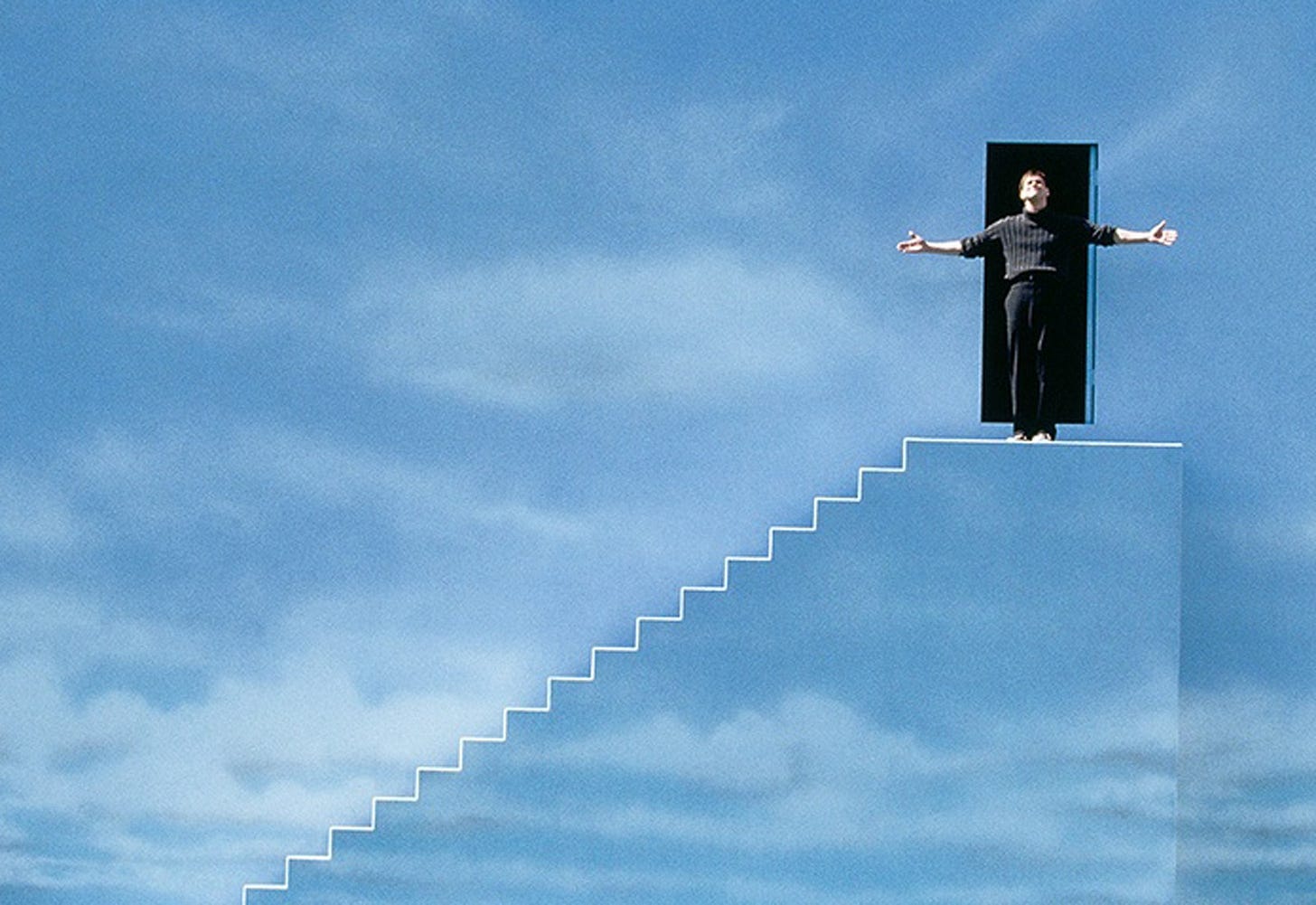

I realize that these final moments are packed with spiritual symbolism. The character of Christof can be seen either as a Christ figure who stands in for the way religion tries to control us, or as an “Off-Christ” (anti-Christ) who tries to keep Truman from understanding the truth. The spiritual allegory isn’t hard to miss — he’s literally speaking from the sky, and when Truman asks who’s there, he tells him he knows Truman better than he knows himself and has been watching him all his life. And, of course, there’s Truman’s literal ascent off the ground and into the sky at the film’s end — he escapes via a stairway to heaven, of all things…and his pose before he bows is so crucifixion-like, you can’t miss it.

Those are fun connections to think about, but I still walk away moved not by the spiritual allegory but the very existential dilemma we’ve just watched. Carrey, as I said, is fantastic — by the end of the film, Truman has evolved into a curious, soul-searcher who’s awakened for the first time in years. More than the critiques of reality TV or the ethical questions posed, I’m moved by the all-too relatable story of a man who woke up to find himself trapped in a comfortable life, haunted by the feeling that there must be something more.

Twenty-five years later, The Truman Show still has power because of its human story. Like Truman, I’m surprised by the voices that still whisper to me. I wonder about some of the less-wild lovers I’ve let seduce and distract me, pacifying me from my desires and dreams. I wonder if I can throw caution to the wind, sail to the end of my world and see what’s on the other side. Like Truman, we’re all searching. Like the rest of the world, we want to know how it all ends.

I haven’t read this book in decades, and it will be my only thumbs-up to John Eldredge, whose output after Curtis’ death has been a bit controversial. But I remember being quite taken with the book.

Ah, The Truman Show. I first saw it in theaters when I was 14 and I immediately loved it. It's one of the few great movies that survived both of the major overhauls of my cinematic tastes (the others are the Star Wars saga and Saving Private Ryan). My first overhaul was when I was about 16 or 17: I began to view movies through an artistic lens and became a true film buff. The second was when I was about 25 or 26: I began to te-evaluate movies through a spiritual lens when I became more devout and decided not to be a fully active film buff anymore. Movies are pretty much a hobby for me now. I wrote a small essay on The Truman Show in my early 20s but it definitely wasn't as deep as yours. Great job!