People in the 1990s loved John Grisham.

The novelist is still cranking out legal thrillers – he actually has a sequel to The Firm coming out in October – but he hit peak popularity in the nineties. Grisham, Michael Crichton, Tom Clancy and Stephen King were titans on the best-sellers lists, and in my teenage years, I devoured anything they released.

The books’ fast-paced plots and straight-arrow heroes made them great fodder for films. We’ve already discussed the summer of 1993’s first of two Crichton-based films, Jurassic Park (the second was Rising Sun, which is best left undiscussed), and 1993 was sandwiched by two Jack Ryan movies, 1992’s Patriot Games and 1994’s Clear and Present Danger. Next month, we’ll discuss August 1993’s big Stephen King adaptation, Needful Things.

But there was a period when Grisham provided the inspiration for the biggest movies with the biggest stars. Later in 1993, Julia Roberts and Denzel Washington would headline The Pelican Brief, and Susan Sarandon, Tommy Lee Jones, Samuel L. Jackson, Sandra Bullock and Matthew McCounaghey would all populate the casts of The Client and A Time to Kill. In 1997, no less hallowed a director than Francis Ford Coppola took a swing with a little-known actor named Matt Damon in The Rainmaker.

It’s easy to see why so many stars and directors flocked to this material. They were nearly sure-fire hits, based on best-sellers that could be made without gigantic special-effects budgets, and they gave actors meaty dialogue to tear into. Legal thrillers were huge, especially following A Few Good Men, and these were the days when you could still make good money off of mid-budget adult dramas.

And none were bigger than The Firm, particularly when it came to Grisham adaptations. It helped that the book was a runaway sensation; his second novel, it catapulted him to success. The R-rated film was the third-highest grossing movie of 1993, bringing in $158 million in the United States and another $111 million across the globe – a spectacular success for that time, particularly considering its moderate $42 million budget. No other Grisham adaptation has made more money – and no other Grisham adaptation has a better cast at its disposal (although I’d hear an argument for A Time to Kill).

I read the book shortly before the movie came out, but I honestly don’t know that I’d seen The Firm all the way through prior to this viewing. My parents weren’t letting me watch R-rated movies at that time, but I remember they loved it enough to rent it on the hotel TV when we took a family vacation. They thought my siblings and I were asleep, but I half-watched it while dozing in and out. So, this was really my first time watching The Firm in its entirety.

How’s it hold up? Let’s talk about it.

The job from hell

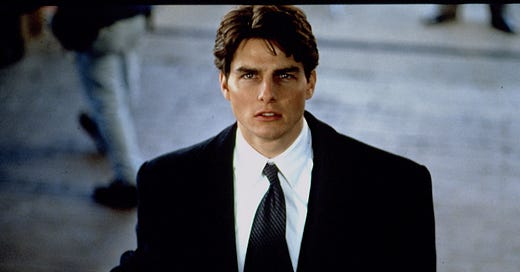

The Firm is about Mitch McDeere (Tom Cruise), who’s graduating from Harvard Law in the top of his class. The film opens with a montage of him meeting with recruiters, all of whom are eager to pay big. Mitch accepts an offer with small Memphis law firm Bendini, Lambert & Locke, who promise him 20% more than his top offer and are willing to toss in a low-interest mortgage and a BMW. Mitch and his wife, Abby (Jeanne Tripplehorn), head down south to start their new life. But it’s not long before Mitch begins to suspect things are not on the up and up at his dream job – two associates suddenly dying in a mysterious explosion will do that, as will a random visit from an FBI agent (Ed Harris), who recruits Mitch to do some spying and potentially illegal ratting on the firm’s slimy clients. Is the FBI right or are they just trying to get Mitch to do their dirty work for them? And is Mitch willing to throw away his lavish life and legal career to be a government pawn?

It’s been a while since I’ve read Grisham’s novel, but I recall it being a fairly hefty paperback. The appeal of his writing was that he could spin a complex plot, pepper it with arcane legal details, and still make his novels fleet-footed and thrilling. That’s harder to do in a movie, even one spanning more than two and a half hours, and The Firm’s biggest flaw is its screenplay by Grisham, Robert Towne, David Rabe and David Rayfiel, which struggles to juggle legal minutiae with its more ludicrous genre elements. It’s both too silly and too convoluted at once.

The film sets up the firm as shady from the get-go. Less than five minutes into the film, Abby and Mitch are wooed out to Memphis for a get-to-know-you meeting, and Abby’s already concerned about the control the partners seem to have on their personal life. They encourage happy, close-knit families and having kids quickly because it “promotes stability.” From the moment Mitch receives an envelope with his salary offer, we’re prepared that something is off with these associates, rather than given a slow burn where we feel discomfort alongside Mitch.

And I get it, that’s not the story that they’re telling. The question isn’t whether Mitch will realize that his employer is evil so much as whether he’ll care. The story sets Mitch up as an ambitious upstart looking to escape the poverty and dysfunctional family life he grew up in, so much so that he neglects to tell his future employers that his brother (David Straithairn) is in prison. But we don’t get much time to see Mitch enjoying his newfound luxury; sure, the firm buys him a fancy car and big house, but Mitch’s first day also includes hints about mysterious closed-door meetings and shady security experts. Within the first half hour, he learns that two of the firm’s partners have died in a mysterious boating explosion in the Cayman Islands – which, sure, could be just a weird coincidence, but it’s not too long after that when Mitch is solicited by Harris to get them the dirt on the firm’s mob clients.

That doesn’t make The Firm a bad movie; it’s actually a really entertaining one. But it’s worth remembering that when we applaud the days of R-rated adult thrillers, we weren’t always talking about anything overly serious or deep. The legal setting for The Firm – and, let’s be honest, the vast majority of Grisham’s novels and their respective adaptations – lent a patina of sophistication and intelligence to otherwise generic thrillers and pot-boilers. They were the film equivalents of beach reads or airplane novels (and, of course, I read many Grisham books on beaches or airplanes). The script might throw in a lot of legalese and convoluted machinations, but it also tosses in a completely gratuitous sequence where Mitch does backflips with a kid on the street just to set up a later chase in which he has to do gymnastics to hide from killers in a basement.

And honestly, I miss that trashy, silly fun when it’s done right. Pollack was, of course, a hallowed veteran by the time of The Firm’s release, and while nothing he does here recaptures the thrills and suspense of Three Days of the Condor, he knows his way around a thriller. He keeps the pacing up and the chase sequences are effective. He understands how to draw out tension and quicken heartbeats just by capturing sinister looks from his cast – something that I fear we’ve lost as most of our entertainment centers on CGI and explosions – and there are some really solid sequences. I particularly like the moment when Mitch learns the truth about the firm and returns home to tell Abby; Pollack captures Cruise at his most shaken and wired, and the way the film cranks up the music and focuses on Tripplehorn’s reaction as Cruise whispers the truth in her ear is effective. The Firm might be empty calories – and we’ll get to whether its final passages really work in a bit – but damn are they tasty ones, made even more so by Dave Gruzin’s piano-heavy, jazzy score, which was nominated for an Oscar.

The Firm is silly, when you get right down to it. For one, whether Mitch is fine with the money or not, you’d think a Harvard Law grad would be a bit more suspicious of the firm’s cult-like control (there’s probably an essay to be written comparing this film’s enemies to Cruise’s real-life cult adherence), and it seems fishy that the FBI wouldn’t be able to just go after a firm that is pretty notoriously shady and has a long history of partners dying young and violently. It’s also hard to believe that a mob-connected firm that employees top-notch investigators and security experts wouldn’t vet their one prospect enough to learn that he has a brother in prison. They apparently have the time to do the research – no one at the firm seems to do any actual lawyering; instead, most of their time seems to be having closed-doors meetings discussing how to put out the latest fires. And for lawyers laundering mob money, you’d think they’d be a bit more careful about overbilling them (which is how Mitch eventually puts them away without sacrificing his legal career).

After the fact, much of the movie – yes, including the gymnastics – seems laughable. But Pollack keeps it moving so fast that, in the moment, we don’t question it. The film is fast and thrilling. And as any lawyer knows, when you have skilled people making their argument, you might buy anything. And The Firm has a hell of a team on its bench.

All-timers

The Firm was sold as a Tom Cruise tentpole, and that makes sense. There was a long period of time where he was the biggest movie star in the world – and he didn’t even have to risk his life. While I have a lot of affection for stuntman Cruise, I don’t know that he’s ever been more interesting than in the period between Top Gun and Eyes Wide Shut, when he wasn’t just an action star but an actor who wanted to work with directors who challenged him. While it’s great fun to watch him court death in the Mission: Impossible movies, that period where he worked with Martin Scorsese, Oliver Stone, Neil Jordan, Cameron Crowe, Stanley Kubrick and Paul Thomas Anderson was his most fruitful as an actor (it ended in the mid-00s, after great work in Collateral, Tropic Thunder and his Spielberg collaborations, and he started working with people he trusted).

Working with Sydney Pollack would make sense at that time, and the Grisham story gives Cruise a dialogue-heavy role to sink his teeth into, but The Firm is less Tom Cruise in actor mode and more dialed-in as pure movie star. He doesn’t have to do much more than be the loving husband and the focused and intense hero who brings down the bad guys. He’s much better suited at the latter. He and Tripplehorn don’t have very strong chemistry, and Cruise has never been able to convincingly play a suburbanite. But The Firm gives the actor the chance to dig into his strengths: desperate paranoia and righteous indignation. Cruise is strongest in the sequences when Mitch realizes how deep his predicament is and can feel the noose tightening, and the actor’s quite good as Mitch begins to find a third way out of his jam and take control of the situation.

While Cruise is anchoring the film with a star performance, he’s supported by an ensemble that is an embarrassment of riches. Gene Hackman – on any given day, my favorite actor of all time – wasn’t featured in any of the pre-film marketing, but he’s the best thing in the film as Avery Tolar, the lovable scoundrel who serves as Mitch’s lawyer. Hackman had a knack for playing characters who you loved in spite of their despicable nature; he’s a ton of fun to watch here, particularly in the early go as we watch Avery ignore the firm’s strict rules about drinking and womanizing. But near the end, Hackman reveals a depth to Avery that is sweet and sad, and creates one of the few antagonists in the film with depth.

Hackman should have been nominated for an Oscar but was not. The film’s sole nomination went to Holly Hunter as the assistant to a murdered private investigator. On paper, it’s a thankless role – the character sees a murder because she’s in the wrong place at the wrong time, and then she becomes Mitch’s helper. It’s about five minutes of screen time, but Hunter owns the screen for all those five minutes. She’s funny and sad in equal measure, and probably the smartest of the film’s three protagonists. It’s a fun performance, a reminder of how a film can be elevated by the right actor.

And I haven’t even scratched the surface. There’s Wilford Brimley, channeling the good ol’ boy intimidation that Pollack previously pulled from him in Absence of Malice, as the firm’s security operator. David Straithairn does reliably solid work as Mitch’s felon brother. No one is as good a tough guy as Ed Harris, Hal Holbrook is wonderfully slimy, and Gary Busey gets to ham it up a bit as the sleazy private investigator Mitch asks for help. Tripplehorn is largely lost in the shuffle, but fine in her underwritten role. Saw’s Tobin Bell and Breaking Bad’s Dean Norris both show up as hitmen, and Character Actress Margo Martindale appears as a secretary. It’s really a parade of some of the best character actors of the 1990s on display.

They keep The Firm watchable and engaging even when the script threatens to veer off course or tie itself in knots. It holds its final secrets a bit too close to the vest for too long, and I don’t know if I quite understand all of the details of Mitch’s plan. I like the movie’s ending better than the novel’s – here, Mitch doesn’t walk away rich and secure; he says he’ll be looking over his shoulder the rest of his life and he’s giving his money away, which ties into the themes a bit more tightly. But the sequence where Mitch confronts the mob client (Paul Sorvino) and wins them over by throwing the firm under the bus for overbilling feels anticlimactic. While I’m sure the mob likes its money, it seems they wouldn’t just let Mitch out the door that easy, even with all his backup plans.

The Firm is ludicrous. It’s also highly entertaining, and with a great cast at the top of its game. I miss movies like this (these days, The Firm would be a TV series – which they also tried – and while you’d probably be able to handle the legalese a bit more ably, you’d lose the tension), and I miss when our movie stars could give performances not aided by CGI or anchored to IP. It’s not the high point of Cruise’s career, but it’s a solid win.