How ‘Jurassic Park’ made me love the movies

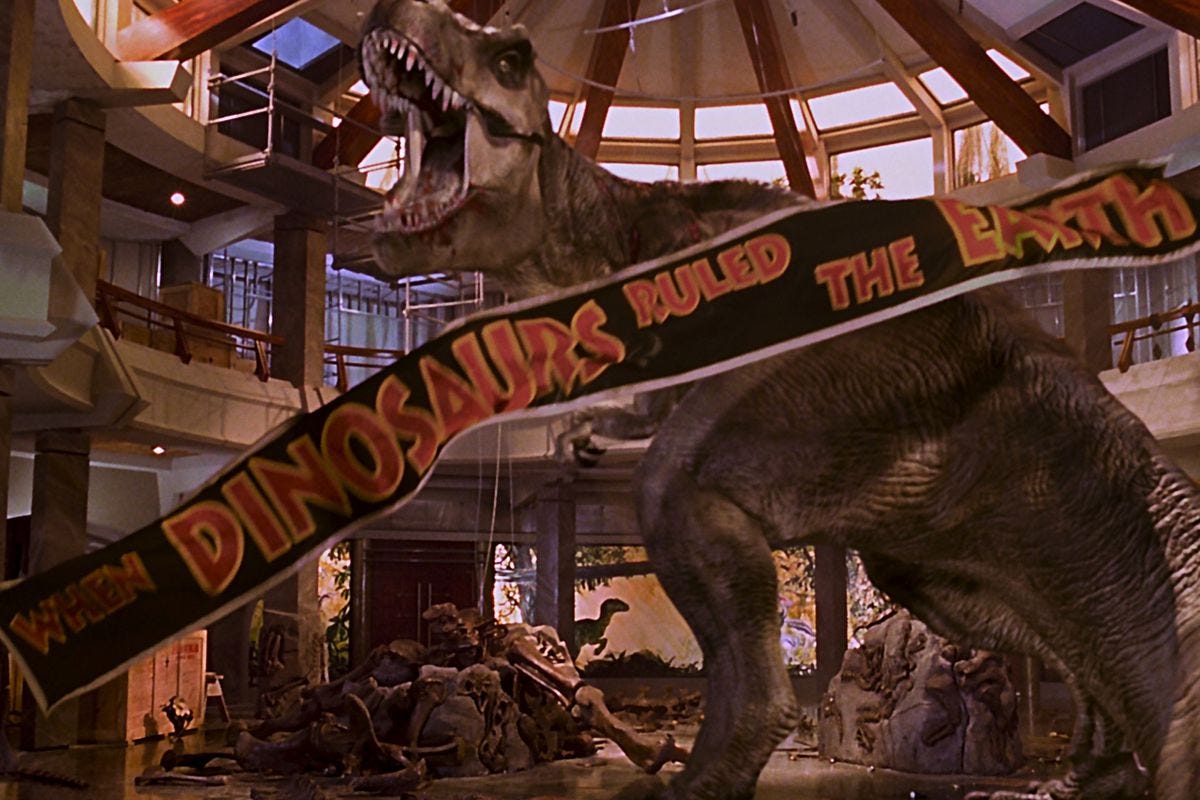

The summer of ‘93 continues with Spielberg’s dino blockbuster.

You can’t talk about the movie year of 1993, let alone that summer, without talking about Jurassic Park.

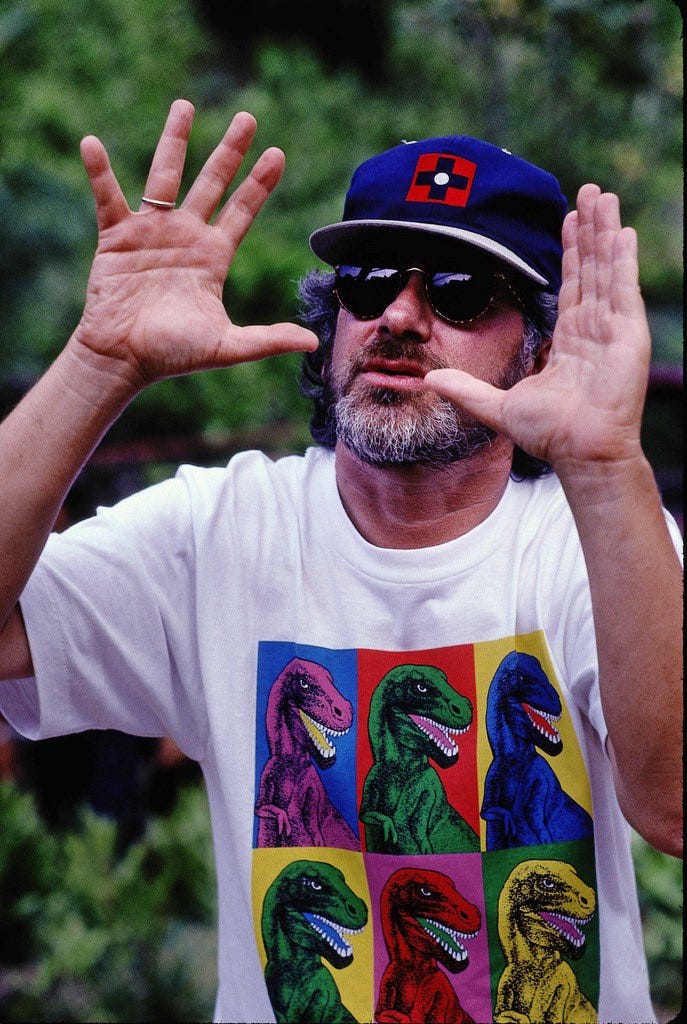

Steven Spielberg’s adaptation of Michael Crichton’s best-seller was the biggest movie of 1993 and, for a period, the highest-grossing film in the world. It ushered in the digital revolution with its computer-generated dinosaurs. After years of mixed critical and commercial reactions, it re-cemented Spielberg as the master of blockbusters and kicked off the best year of his career, which culminated with the release of Schindler’s List. Jurassic Park is important.

Here’s the problem: I wrote about Jurassic Park just last year for my Spielberg Series (which, I swear I’m going to get back to). And as much as I love Jurassic Park, I don’t know that I’d have much more to say about it. It’s a good movie!

But again, I can’t write about the summer of ‘93 and not include something about Spielberg’s movie. Especially since Jurassic Park was the catalyst for turning me into a movie lover. I’d enjoyed film before and even had my own obsession with Who Framed Roger Rabbit five years earlier. But Jurassic Park ignited my inner film geek. When it made a ton of money, I started paying attention to the box office. I wanted to know about the other movies that were coming out. A family friend got me a subscription to Premiere magazine. I was on a path to movie love well before that T-Rex sauntered onscreen, but Jurassic Park sealed the deal.

So rather than re-assess Jurassic Park, I thought I’d take some time to look back on exactly what it broke open in my brain that summer that forever altered my life. So, hold on to your butts; we’re going to look back at my personal recollections of seeing Jurassic Park in 1993.

It was my first immersive movie experience

Jurassic Park doesn’t exactly push the boundaries of its PG-13 rating, but it was the closest I’d come at the time to seeing a scary movie in a theater, without the ability to cover my face with a pillow or leave the room. It was just me and the screen, and a digital soundtrack that shook the theater. As a result, it was the first time I felt totally enveloped and successfully manipulated by a movie, even if I didn’t have words for that experience at the time.

Most of the time watching a movie, I just sat back and enjoyed it; I was also that annoying kid who got a kick out of looking back over his shoulders to see the light coming from the projector. With Jurassic Park, I was transported. My eyes never left the screen. During the T-Rex attack, I didn’t breathe. During Ellie’s attempts to turn on the power in the shed, only for a raptor to jump out at her, I leapt out of my seat and screamed. I grasped the armrest tightly during the kitchen chase.

When my mom picked me up from the theater and asked how it was, all I could say was “it was intense.” It was the first time that a movie got under my skin and caused a visceral reaction. I felt as if I’d been through an experience; my heart was pounding, my legs shaking. I’d never had a movie do that to me before – and I couldn’t wait to have one do it to me again.

It was my introduction to auteur theory

As I said, I’d read Jurassic Park about a year earlier after a teacher had recommended it. And when I heard a movie was being made, I was excited but also nervous. The novel is full of gruesome material – most notably, one character is disemboweled by a dinosaur. There was, in my mind, no way the movie wouldn’t get an R rating.

But then I saw a standee at our local movie theater announcing that this was “A Steven Spielberg film.” And I breathed a bit easier. I recognized that name from movies like Hook and E.T. He made movies I could see! In fact, somehow I also knew that he’d never made an R-rated movie (he’d release his first later that year with Schindler’s List). I was relieved (also because, if I were honest, it meant I wouldn’t see a disemboweling).

There’s a lot that I probably couldn’t articulate at that time, but watching Jurassic Park there were also hallmarks that I noticed that called to mind other Spielberg movies. The sweeping John Williams score. Tension released by a visual gag or funny line. A sense of wonder that painted the dinosaurs as more than monsters. Although I couldn’t put it into words, it was my first time understanding the guiding role of a director and how they brought their own obsessions and quirks to a movie. A few years later, the first book about film I’d ever purchase would be Douglas Brode’s The Films of Steven Spielberg, and I began my first deep dive into a director’s filmography, and my first real understanding that films were more than isolated pieces of entertainment. They were statements, expressions, autobiography.

It made me consider a film’s technical aspects

As I mentioned earlier, I experienced a minor obsession with Who Framed Roger Rabbit back in 1988. The movie (produced, coincidentally, by Spielberg) blew my brain with how cleverly and convincingly it blended animation and live-action. I remember being a bit amazed watching a behind-the-scenes feature of it to learn how they brought the two forms together. And, in 1990, I was curious how they were able to bring the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles out of the cartoon and into live action using puppets from Jim Henson’s Creature Shops.

So it’s fair to say that before Jurassic Park, I understood that films didn’t just happen. There was a craft, a technique, a behind-the-scenes aspect to it. But those prior movies came out before I turned 10, and my interest was usually on an isolated aspect – melding cartoons and live action, making puppets with convincing facial features.

With Jurassic Park, I obsessed over every element. In the weeks preceding the movie’s release, I bought every magazine I could find that detailed how they were using computer effects to bring the dinosaurs to life (later, I’d be even more impressed by the animatronics that actually take up more screen time). I was thrilled to know that something as simple as that shaking cup of water was created by strumming a guitar string underneath. I replayed the intricate shots Spielberg used to heighten the suspense building up to the T-Rex attack, particularly impressed by the timing with which that giant eyeball appears in the car window and how quickly Spielberg cuts from the dinosaur smashing through the sunroof so we think we see more than we do. I noticed how the Williams soundtrack was used to create wonder when that brachiosaur appeared, and I was curious about how loud the movie would be with the much-hyped digital soundtrack.

By the time I saw Jurassic Park, I knew many of the tricks it would have in store. And as I saw it again – seven times – that summer, I’d study the film closely to better understand how Spielberg was working me over. And here’s the amazing thing: each time I saw it, it worked just as well as the first.

It made me think about adaptation for the first time

In anticipation of the movie’s 30th anniversary, I recently started re-reading the Crichton novel for the first time since childhood. My first thought was “why the hell was I reading such a violent book at 12 years old.” My second was amusement at how much I remembered. Not just certain scenes, but lines (particularly a line that specifically says Alan Grant likes kids, when the movie’s version can’t stand them).

As I said, I was apprehensive going into the movie because I was aware how big, intense and scary Crichton’s novel was, and I couldn’t imagine how that might play out on screen. But what I noticed as I watched was that Jurassic Park the movie was a different animal altogether than Jurassic Park the novel.

Oh, the broad strokes are there. There’s a park with genetically engineered dinosaurs, and things have gone wrong. A group of experts come down to offer their insights (and they’re joined by the CEO’s grandkids). Things go badly. But I noticed how much was changed from the novel. Some things – a river chase, a pteradon encounter – were cut likely for time (and both show up in other films). But there were other changes I realized that were made that changed entire characters or the narrative.

For one, the dozens of pages related to the science of the park were largely handled with a quick animated film played for the characters. The lengthy legal scenarios that kick off the visit were largely dispensed with. Alan Grant, as I said, went from being an affable person who liked kids to a bit more of a curmudgeon who learned to be okay with them; he was also given a romance with his co-worker, Ellie. Rock star mathematician Ian Malcolm was a bit funnier and less annoying than he came off in the book; he also got to live in this version (Crichton would later resurrect him for the novel The Lost World). John Hammond, played by Richard Attenborough, was a much friendlier, grandfatherly character than the gruff and greedy multibillionaire in the book (Hammond also gets to live in the movie; in the novel, he’s dinosaur food).

Again, we’re talking about things that I’ve only been able to put words to in the ensuing decades, but I realized that Jurassic Park the movie was both the same story as the book and its own thing. The novel was a rousing, even scary adventure. The movie had a bit more heart, and it still brought the scares. The themes were largely the same, but there’s a cynicism that cuts through Crichton’s novel that Spielberg’s movie lacks. And I realized how a movie could deal with certain things more economically than a novel, and how a novel could take more time to develop a rich world.

As a kid, I held up that Jurassic Park the movie was great, but the book was actually better, probably because it was one of the first “grown up” books I read and I had that teenage belief that dark and edgy were synonymous with maturity and quality. Reading it again, there’s a didactic nature to Crichton’s novel and a cynicism that I think make it a bit of a bitter pill. Spielberg takes the best moments of Crichton’s novel, gives them a bit of heart and wonder, and makes everything run efficiently. It’s also, of course, just more fun to actually see the dinosaurs.

It was my first experience as a movie ambassador

I was always known as a kid who talked about movies. A neighbor's family called me ‘Entertainment Tonight’ because I wouldn’t shut up about what movie was being made or what was coming out next. But up until Jurassic Park, I was kind of just a nonstop fountain of useless movie information and facts.

Spielberg’s movie sent me out of the theater on a mission.

It started with my mom. She picked my friend and I up from the theater and I couldn’t stop telling her about the impact the movie had on me. I was babysitting my cousin that afternoon, and I enthralled him with stories about the scary dinosaur movie. I blabbed to all of my friends about it and dragged them to the theater and back several times throughout the summer. “You have to see this,” I said. “It’s so good. So scary.”

Now, I’m not going to pretend to foster any delusion that a 13-year-old brat from the suburbs of Detroit played much of a role in Jurassic Park’s record-breaking success. And the movie was fated to be a hit – it had Spielberg, it had dinosaurs. It needed nothing else. But I still considered it a personal victory when I was on a trip and called home to talk to my mom and she said she’d taken my brother to go see it – and then he said he loved it. I took friends or accompanied family to their first viewings, telling them they weren’t ready for it, and then took immense pleasure watching them jump out of their seats at the scary moments.

Spielberg brought the dinosaurs to life, but he also created a movie monster. There was no going back after Jurassic Park. I was obsessed. I had to go back in a week and see whether The Last Action Hero was as bad as people were saying (we’ll talk about it next week). Later that summer, I obsessed over The Fugitive. One year later, my aunt bought me a journal and I started scribbling my thoughts about the movies I saw. Two years after that, I’d write my first official review – about Broken Arrow for my high school newspaper.

Jurassic Park isn’t my favorite movie; heck, it might not even be in my top 10 Spielberg movies (although it’s close). But it’s a milestone in my history as a film lover. It made me. At age 13, I knew something had changed in my relationship to films, but I couldn’t foresee what an unshakeable obsession had been created. And it gets refreshed every time I go back to Isla Nublar.

No; the area of Warren I lived in was right on the border of Warren and Madison Heights (696 and Dequindre area), so I actually saw it at the Star John R in Madison Heights. But when I was in my 20s and lived in Warren/Roseville area and all my friends were from Sterling Heights or Clinton Township, I went to the Star Gratiot a lot!

Did you see it at the Star Gratiot?