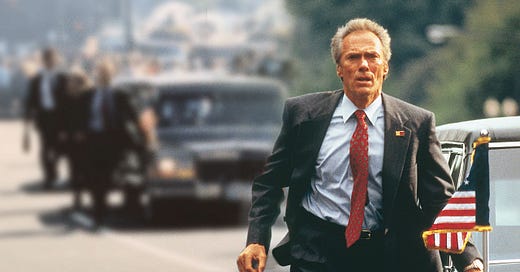

Summer of 1993: In the Line of Fire

Clint Eastwood and Wolfgang Petersen team for a tense, smart thriller.

It’s cliché to say they don’t make ‘em like they used to, but that was the thought that ran through my head several times while watching In the Line of Fire. It’s the type of R-rated, grown-up, meat-and-potatoes thriller that dominated the big screen before sequels and IP-based franchises took over.

Coming just a week after The Firm – a similarly adult-oriented, but far sillier, thriller – it’s the type of movie for which critics invented phrases like “crackerjack suspense.” It’s smart, suspenseful and more thoughtful than most films of its type, even if greatness is likely the farthest thing from its mind. It’s a classic I’d forgotten almost everything about, and revisiting it was one of the pleasures I get from doing these little retrospectives.

Clint Eastwood stars as Frank Horrigan, a U.S. Secret Service Agent who holds the dubious reputation of being the only active agent to have lost a president in the line of duty; he was on the security detail in Dallas in November 1963. Frank spent the years after wrestling with alcoholism and divorce. Thirty years on, he works with a young recruit (Dylan McDermott) in the field, where he busts counterfeit rings and investigates the myriad crackpots who call in with threats to the president’s life. Except one time, the threat appears valid. A mysterious man named Leary (John Malkovich) has left his apartment decorated with shrines to previous assassins, and when Frank investigates, he receives a call from the wannabe Booth, who plays the traditional cat-and-mouse/”we’re not so different, you and me” game we’ve seen in these movies before. Frank asks to be assigned to the president’s detail alongside a dubious young agent (Rene Russo) and try to solve the case.

Clint Eastwood is one of our most iconic actors, as well as one our most prolific directors (to be candid, when I revisited this, I was surprised to remember it was a Petersen film, not one of Clint’s directorial efforts). While I’ve reviewed and enjoyed several of his films – including Million Dollar Baby, Mystic River, Sands of Iwo Jima, Gran Torino and Richard Jewell – I haven’t written much about him as an actor. His heyday in Westerns and cop thrillers was before my time; even if I enjoy A Fistful of Dollars and Dirty Harry, they aren’t films I have an overabundance of love for. And his later performances are competent, but largely fall into the same grizzled old man category that has long become stereotypical for him.

Revisiting In the Line of Fire, I was pleasantly surprised with how much I enjoyed his performance. Eastwood was in his early 60s when he filmed this, and I respect how he leans into that instead of portraying Frank as a still-got-it tough guy. Frank is old and out of place with the younger agents; he’s sexist, describing female FBI agents as “window dressing,” but he isn’t proudly out of step. He’s willing to learn and accept that maybe the times are passing him by; his age is certainly on his mind when he’s winded running alongside the president’s limo.

Eastwood is so iconic as the hard-edged Dirty Harry and the steely Man With No Name that it’s easy to forget the sensitivity that’s shown up in his work in recent decades. Sands of Iwo Jima is the rare film to put a face on U.S. adversaries during World War II, and many of his later films have an elegiac, mournful quality. Some movie stars avoid getting older (he says on a weekend where 60-year-old Tom Cruise is jumping off plans); Eastwood has been grappling with his mortality for the last 30 years.

Frank Horrigan might actually be among my favorite performances from the actor. Eastwood is weathered and has moments of brooding, but he also brings a wry humor and charisma. He can toss off a joke with a wink, and I particularly enjoy how he decompresses from stress not with the cliched beer in his trailer but by playing piano at the local bar. Don’t get me wrong; Eastwood still knows how to intimidate (I particularly love his growl of “I’ll be thinking about that when I’m pissing on your grave” to his stalker), but the performance is also leavened and gentle in places. I initially thought his relationship with Russo’s character was going to devolve into cringe, but their romance is sweeter and more charming than you would expect. There’s a funny scene where they go through the rigmarole of removing their guns, handcuffs, uniforms and bulletproof vests before getting into bed together; she’s called away on a work emergency and the camera lingers long enough for Frank to moan “now I gotta put all that shit back on.”

Eastwood also handles the action sequences well. He’s not Tom Cruise, but he’s not afraid to get physical in an age where CGI wasn’t yet replacing all the danger. The film opens with the standard tense showdown where Frank cavalierly risks the life of his partner to get the bad guy, and the actor is still believable as a bit of a livewire. There’s also a mid-film chase across the Washington, DC, rooftops – side note: I miss foot chases across rooftops – where Frank dangles from a ledge. As he’s doing so, items clatter to the ground below him, proving it’s really Eastwood and not a stuntman hanging from that ledge.

As good as Eastwood is, Malkovich walks away with the movie. By now, his smartest villain in the room routine has become a bit predictable, but here you can see Malkovich perfecting it. Leary is smart and pissed off – he’s not just a random nut job; he’s a man trained to kill and he’s been damaged by it. Malkovich rarely raises his voice above a whisper and is more terrifying for it. During Leary’s calls with Frank, you can almost pick up a sadness to the would-be assassin, an acknowledgement that he knows how damaged he is and is disappointed by it. But then he’ll also kill two curious hunters in cold blood or murder bank tellers to cover his tracks and you’re reminded your sympathy can only go so far. It’s a great performance, and you can see why Malkovich was nominated for an Oscar (he lost to an actor for a film we’ll get to in a few weeks).

Much like The Firm, In the Line of Fire is another adult thriller with a cast that’s a who’s-who of character actors. I’m bummed we don’t see much of Rene Russo these days; I always appreciate her smart characters and their willingness to go toe-to-toe with their male counterparts. McDermott’s role is small, but I liked his rookie who’s too rattled to stay in the game much longer – and the film pulls from the Dirty Harry tradition of having him be goaded into sticking around long enough for it to have tragic consequences. John Mahoney, Fred Thompson, and Gary Cole also class up the cast. And, just a week after he played the albino assassin in The Firm, it was funny to watch Saw’s Tobin Bell pop up again as a low-level scumbag in the film’s opening scene.

I don’t know that Petersen ever topped the nightmarish claustrophobia of Das Boot, but In the Line of Fire started a run for him that made him one of the top action directors of the 1990s, following this up with Outbreak, Air Force One and The Perfect Storm. Petersen, who died last year, had a preternatural knack for building tension and staging large-scale action sequences. In the Line of Fire is a bit lower-scale than his work would eventually become, but he captures the suspense of the cat-and-mouse-game well, and in addition to the aforementioned foot chase, the film also builds to a fantastic climax in a hotel elevator, which mixes high-stakes fireworks with a battle of wits between Leary and Horrigan.

Jeff Maguire’s script is smart and taut, and littered with little character grace notes for Frank. It takes time near the end to delve into Frank’s guilt over the Kennedy assassination, including a moving and vulnerable moment for Eastwood as an actor. And the film is interested in the sacrifice required of a Secret Service agent – is Frank willing to die for his boss? Should he be upset he’s still alive? There’s a bit of lip service paid toward the idea that Leary is trying to push Frank from a role of protector to killer, but I wish the film had played a little more with that psychological aspect; there’s never too much danger that Frank is going to be pushed off the edge, mainly because Eastwood doesn’t seem ready to relinquish his charm.

But does that keep In the Line of Fire from being a great film? I don’t really think so. I think after winning an Oscar for Unforgiven, Eastwood wanted to prove he could also be in a straight-down-the-middle action thriller, and he didn’t want anything too flashy or pretentious. In the Line of Fire is less a movie that never achieves greatness so much as it is a mainstream actioner that exceeds its grasp. It’s a classic.