Is ‘Sinners’ anti-Christian?

Ryan Coogler’s vampire movie enters into the relationship between faith and American evil.

This post contains spoilers for Sinners.

I was still on my Lent break when Sinners screened for the press, and I was unable to see it opening weekend. So, I’m late to the conversation. On Monday, I took the day off work to recover from the busy preceding days, and I dropped the kids off and went straight to the theater.

Because I’m coming to Sinners well after its opening, I’m not going to write a full review, although Perry and I will hopefully discuss it very soon for We’re Watching Here. I’m well in line with those calling it one of 2025’s best films so far. I’m a Ryan Coogler fan all the way back from Fruitvale Station. I think Creed is the pinnacle of legacy sequels, and Black Panther is Marvel at its best. I may not love Wakanda Forever, but I blame factors well outside of his control for that mess.

But I didn’t know Coogler had this in him. Sinners is many things – a red-blooded (literally) horror movie, a genre look at Jim Crow South and the evil of white supremacy, and a rip-roaring testimony to the power of the blues. Its standout sequence – you know the one – is the most audacious moment I’ve seen in a big studio movie in years, using music as a conduit to bend space, time and reality. The movie is tense, scary and masterful.

Is it also anti-Christian?

The first person I saw suggest this was the rapper Lecrae, who took to social media to laud Coogler’s directorial prowess but suggested that the film had some “anti-Christian propaganda” and that Coogler might be working through some “church hurt.” Other influencers jumped in, some backing up Lecrae’s theory while others stated that just because a movie doesn’t center Christianity doesn’t make it anti-Christian.

I didn’t dismiss this question, and a large part of that is because I have a lot of respect for Lecrae, an artist whose work I admire and who’s shown courage to speak out on issues of faith and justice. He’s not paranoid or prone to chasing controversy for its own sake.

Also, he might have a point.

Let me clarify: I don’t think Sinners is anti-Christian propaganda, nor do I believe that Ryan Coogler set out to make a movie that tears down faith. I do, however, think the film enters into tensions in regard to Christianity’s history in America, particularly on issues of race and power. It made me feel uncomfortable; that’s the point.

We’re going to talk about it – and again, spoilers – but I want to stress that I’m untangling this as I write, and after only one viewing. I will miss things, and subsequent viewings – and there will be subsequent viewings – will reveal more, and potentially further shape my views.

It’s worth stressing that the film’s not primarily concerned with matters of faith. It’s definitely commenting on the role of Christianity in the American South, but largely as a tool of bigger themes. And Sinners has a lot on its mind. The movie’s a masterpiece, but I won’t deny that it’s a messy one. Hearing the description of a movie about vampires in Jim Crow South, it’s easy to think the conflict boils down to “racist vampires.” Coogler’s film is more complicated than that, grappling with so many themes that it feels ready to burst. Its messiness is one of the things I love – it prompts questions instead of giving answers – but it also means that talking about some of these themes will get squishy.

I suppose that by calling a movie Sinners, you can’t avoid religious comparisons1. The film is bookended by scenes in a church. As it opens, we see young Sammie Moore (Miles Cayton) walk into his father’s church, beaten and bloody, clutching a broken guitar. He was supposed to be in the service helping his father lead worship – the film flashes back to the previous day and night to showcase the events that led up to this moment; we return to the church at the end of the film.

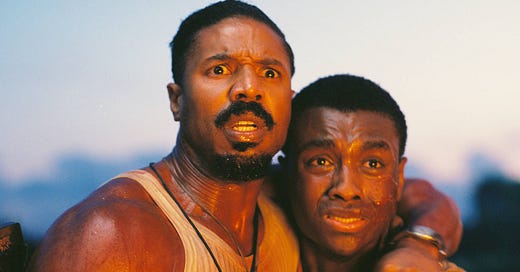

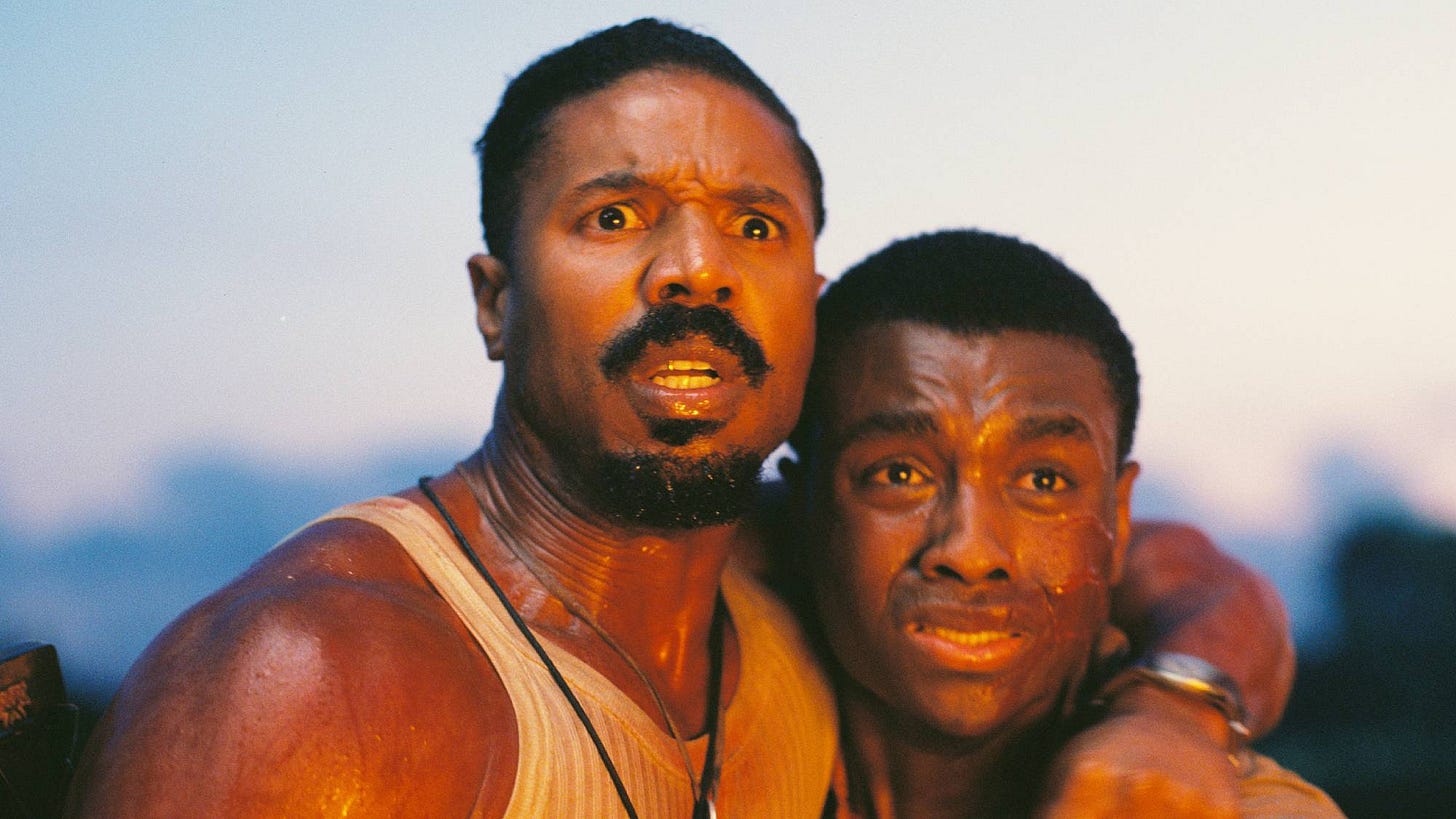

Sammie spent that previous day with his twin cousins Smoke and Stack, both played by Michael B. Jordan. The brothers have returned from Chicago, where they’ve wracked up a crime career alongside Al Capone and – likely illicitly – come into a small fortune. They’ve returned to Mississippi to carve out their own empire, starting with opening a juke joint in an old factory, where they’ll sell Irish beer and bring in Sammie and a local guitar legend (Delroy Lindo in another of his great late-period performances) to play the blues. Eventually, the vampires show up, but I love that Coogler luxuriates in this first hour, letting his characters breathe and immersing us in this world.

There are hints throughout that the supernatural is waiting to break through. Sammie’s dad very much believes in a good/evil divide; he believes his son’s musical gift belongs in the walls of the church, and that carousing with his cousins and playing the blues could be a conduit for evil. Smoke’s ex-wife is a mystic who believes in demons and spirits, and that Smoke’s safe return is due to spiritual protection she’s requested. The film’s prologue introduces the idea that music holds a power to pierce the spiritual realm, drawing kindred spirits but also attracting demonic entities.

Which, of course, is exactly what happens in the film’s pivotal and unforgettable music sequence, where Sammie – in a song that references his father’s religion and his preference for the blues over gospel – plays a song that bends space and time. It also attracts a group of vampires2 eager to bring Sammie to their side.

This is where you’d think the religious twist will come – and it does, but not from Christianity. Or, at least, not from what we think of as American Christianity. Smoke’s wife, Annie, uses her knowledge of hoodoo and mysticism to identify the vampiric threat and teach the others how to fight. Some traditional vampire lore still holds – much of the film’s suspense is rooted in the idea of vampires having to be invited in, and they still don’t much like garlic (there’s a sequence involving a garlic test inspired by the blood test in The Thing). But crosses don’t seem to have much effect.

As Lecrae points out, Christianity seems to be irrelevant or ineffective against the vampires. The clearest example occurs near the end, when Sammie is nearly caught by the lead vampire. In a last-ditch attempt to save himself, Sammie begins to recite the Lord’s Prayer. At first, it appears to work. But then the vampires begin to recite the prayer themselves. What actually buys Sammie the time to save himself? He smashes his guitar into the vampire’s head, buying enough time for Smoke to stab the vampire through the heart. The music of the supposed sinners is what saves him.

So, what’s happening? What is Sinners saying about Christianity – which, in most vampire stories, seems to be the greatest foil against these beings?

It’s worth noting, as my fellow Michigan movie critic Michelle Kisner points out in her review, that Sinners is a movie fascinated by duality – it is, after all, centered on twin brothers. Most of the characters aren’t easily categorized. Smoke and Stack are both admired and feared by many in their town; the protagonists are also criminals. Stack’s love interest, Mary, is of mixed race. Even the Irish vampires aren’t presented as the film’s biggest villains; before the white men made the Black community the focal point of their hatred, the Irish were targets. Part of what makes the vampires’ arguments compelling is that they promise everyone freedom and power over their shared enemy.

All that to say, Sinners doesn’t tie things up into tidy categories. So I don’t think there’s one overarching point Coogler is making about whether Christianity is a force for good or evil. It could be both – just as Sammie’s music attracts both good and bad spirits.

My first thought was that maybe Coogler was making a point about Christianity when it is not fully embraced or believed. The scene with the Lord’s Prayer recalls a similar moment in Stephen King’s novel ‘Salem’s Lot, in which Father Callahan tries to ward off vampire Barlow with a crucifix – only for his doubts to overwhelm him. I think maybe there’s something to that – at the end of the film, we see Sammie reject his father’s plea to put down the guitar and join the church, instead committing his life to the blues. He’s potentially not a true believer.

But I don’t think that interpretation quite works. Yes, Sammie’s embraced music over religion as his true calling. He says as much in his song. But to say that Sammie’s prayer fails because he doesn’t follow the true religion ignores the fact that the guitar and music do appear to have true, mystical power. The reveal is not that Sammie doesn’t have faith – it’s the object of what his faith is in. And in Sinners’ world, it’s the blues – Black culture – that have the power.

I use that word intentionally, because power is a major theme of Sinners. Everyone is trying to get power over everyone else. Smoke and Stack left Mississippi to make a name for themselves, but found themselves at the mercy of the same forces that kept them down at home. They return to the Delta to wield power on their own terms. When they order food for the party, the clerks at the grocery store barter and negotiate – their way of taking power over the situation. When the vampires arrive, the battle of power over whether they’ll be able to trick the people in the juke joint into inviting them in.

But the true threat in Sinners is white supremacy. Smoke and Stack think they’ve pulled one over on the racist men of the town by purchasing their factory with a giant wad of cash; the vampires alert them that the KKK – who, contrary to what has been said, we see as still very much active in the town – are coming to kill everyone the next morning (as the film’s final scenes show, this is not a lie). In the end, they still have the power, and one of the film’s themes is the attainment and wielding of power.

And what was one tool white men used to wield power over slaves and, even after slavery, the Black community? Old-time religion.

At one point, someone makes the comment to Sammie that the religion his father follows didn’t originate with their community. It was forced upon them by the white men; the blues, by contrast, is part of the Black community; the only thing that’s truly theirs, Lindo’s character says.

Coogler’s point isn’t to argue the veracity or effectiveness of Christianity. But the faith is, however, crucial to the themes of who wields power and the complicity of institutions. Christianity has brought benefits to the world, both for individuals who believe it and those it has served through its churches, hospitals and orphanages. There were Christians who preached against slavery, here and elsewhere. Preachers fueled the civil rights movement. Much of the Black community still holds to and finds hope in the faith.

But that faith grows rancid and corrupt when it’s used as a tool to amass and keep power, which is what Coogler is addressing. Christianity was forced on the Black community – as well as the native American community. Preachers twisted the Bible to support slavery and to keep slaves obedient. Biblical teachings were perverted to argue against the humanity of Black individuals3. Sammie’s choice is to lean on a tool that was used against him or to embrace his history, culture and heritage.

Whether that precludes Christianity is beside the point; maybe a sequel addresses this in more depth4. And Ryan Coogler’s views on Christianity itself are beside the point. Maybe he does think it’s been harmful. Maybe he does have some church hurt. That’s not important here – he’s making us consider Christianity as one of many tools that have been used to rob a culture of identity, and to assimilate and control.

As a Christian – particularly as a white Christian – it’s not my place to critique or judge Coogler’s use of the faith. It is, however, my responsibility to see it clearly and acknowledge that, while I believe in and follow Jesus and can attest to the changes he’s made in my life, the faith I cherish has, at times, been weaponized and used as a tool for wicked purposes. Sometimes, it’s still being used that way. Whether Coogler and I share the same perspective on faith is irrelevant; I understand what he’s doing, and I think it’s an effective tool in a masterful movie. I look forward to diving into these themes and others on the many, many rewatches I hope to have.

If the title wasn’t already taken, this movie could also have been called The Blues Brothers.

Can we take a moment to celebrate that a studio movie featuring a time-warping blues singer and folk-dancing Irish vampires took in $48M its opening weekend and looks to be rocketing ahead nicely?

I am far from an expert in these issues, and I simply will direct you to Jemar Tisby’s fantastic book The Color of Compromise for better historical background.

The film’s mid-credits sequence is the epitome of how these scenes should be used; it’s a true epilogue. I’d also be open to a 90s-set sequel involving hip hop vampires.

This is such a good take. The movie seems to be clearly about how Christianity has been used by the white community to disempower the black community in order to subjugate them.

The way the vampires tried to convince the people in the juke joint to convert and joint them was exactly like how some Christians evangelize ("we'll give you love, fellowship, unity, and eternal life").

If you accept the vampires' call, you lose your true identity as a member of the black community (you stop singing the blues and you start singing Irish folk songs). If you accept the Christians' call, same thing - you stop singing the blues and you start singing church hymns from white europeans.

If you accept the vampires into your heart, you lose your freedom to live half the day. If you accept the Christians into your heart, you lose your freedom to live an independent life with your own identity and instead work in near slave conditions as a sharecropper on a white man's farm.

And just in case the parallel wasn't clear enough, the vampire conversion attempt ended with the leader of the group trying to baptize Sammi in the river as a member of their flock.

It isn't a comment on Christianity as a whole, I don't think, just on the corrupt way it has been used as a tool to subjugate the black community in America. You're the first person I've seen who recognized that so clearly.

I don’t know if you stayed for the second post credits scene, but it’s a little clip of young Sammie playing This Little Light of Mine while sitting in the church, and then (at least, it’s how it read to me) glancing reverently upward. Just an interesting bookend which might imply Coogler isn’t as down on all of it as some might claim.