It’s hard to overstate how big a deal Jim Carrey was in 1994, particularly if you were a teenage boy. Within the course of one year, he went from being “the white guy on In Living Color” to the star of three of the most popular films of the year – Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, The Mask, and Dumb and Dumber.

I honestly can’t think of a comedian who had that meteoric a rise in such a short time – one that immediately placed Carrey among the most bankable stars in Hollywood, earned him a spot in a Batman movie the next year, and within two years made him the first actor to earn $20 million for a role (in a movie that audiences then roundly rejected).

I imagine those who weren’t born in the last century might be perplexed, thinking “The villain from Sonic the Hedgehog and Mr. Popper’s Penguins?” And it’s true that it’s been a long time since Carrey has been a box-office juggernaut. And it’s also true his acting choices changed radically even a few years after 1994 – four years later, he’d give one of his best performances in the drama The Truman Show. He’s flitted back and forth between comedy and drama, revealing a knack for angsty, sensitive performances, and today he’s largely retired, occasionally writing novels, creating paintings or musing about the psychological damage of fame.

But in 1994, he was just another funnyman trying to make teens laugh. And he was good at it! I was an avid In Living Color fan, and while I never thought Carrey was as funny as, say, Damon Wayans on that show, characters like Fire Marshall Bill made me laugh. And he was an actor who’d been kicking around in bit parts for a few years, most notably with supporting roles in Peggy Sue Got Married and The Dead Pool (the Dirty Harry one, not the Ryan Reynolds one). But nothing suggested he was about to become a global superstar until Ace Ventura: Pet Detective became the first sleeper of the year, opening on Feb. 4 and topping the charts for its first two weekends, grossing $24 million in its first 10 days (on a $15 million budget) and ultimately grossing $72 million in the United States and $35 million internationally. Carrey’s three 1994 releases would ultimately gross a combined $550 million, and he would place just behind Tom Hanks as that year’s most bankable star.

So, throughout this year, I’m going to take a look at his first three movies, dropping by to revisit The Mask this summer and Dumb and Dumber in December (this year also features anniversaries for two of Carrey’s most acclaimed dramas – Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and Man on the Moon, and I’m hoping to revisit those as well). And we’ll start with Detective Ventura.

I didn’t see this in theaters, but I can conservatively estimate that I saw it a billion times on VHS. I think I avoided it because the previews made it look like the type of loud, crass yuk-fest I imagined myself too mature for. But I was also 14 years old, and when it became a hit, I decided to check it out to see what the fuss was about – and realized I wasn’t as refined as I thought. I still recall watching this on a random weekday afternoon at my parents’ house, doubled over in laughter during the opening scene as Ace, disguised as a delivery man, bops down a street, totally decimating a package. As I’m sure everyone our age did, my friends and I delighted in repeating the film’s dialogue over and over – particularly the looping way Carrey turns words like “really” and “loser” into polysyllabic journeys. I laughed at the way Carrey moved like a live-action cartoon, a special effect who needed no computer assistance. And I loved how he talked through his butt cheeks. Fourteen is a hell of an age.

If I ever need to question whether I’ve matured, my reaction to Ace Ventura 30 years later is proof. This is a movie that has aged like a gallon of milk set out on an Arkansas porch in August. While it has its sporadic laughs, it’s a horribly immature and dated piece of work, full of homophobia and transphobia that I can’t imagine even passed muster in the early 1990s, and centered on a character who is a completely repellent sociopath. Shall we take a look? Alrighty then.

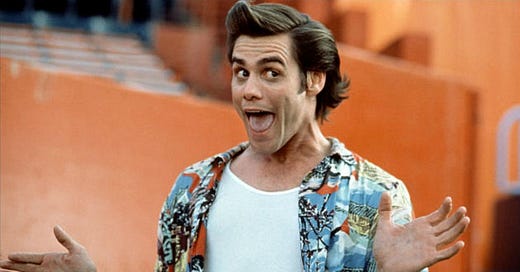

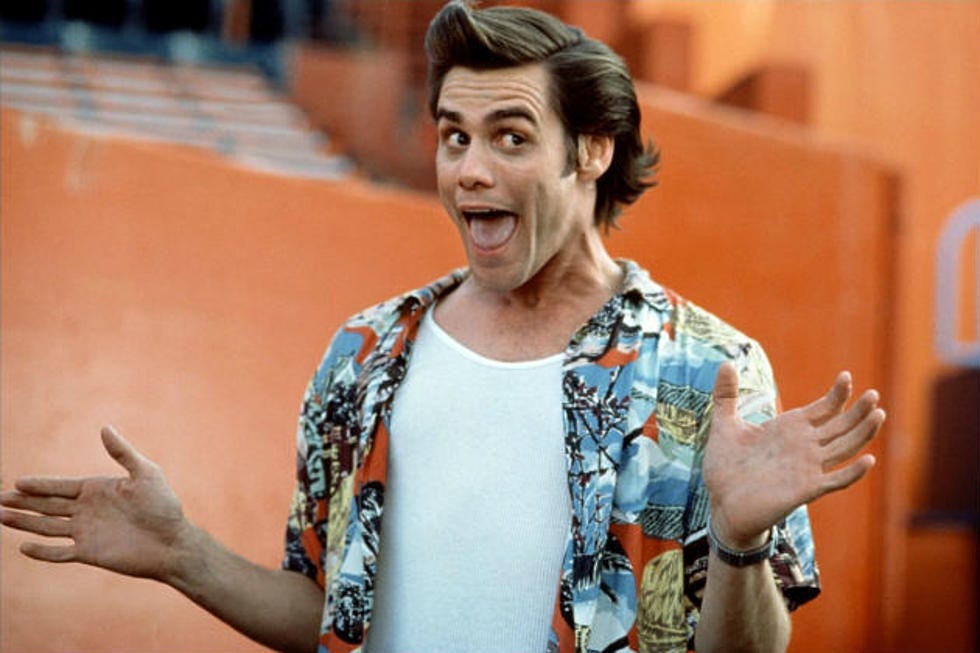

Jim Carrey unleashed

Before I dig into my criticisms, I have to acknowledge that Carrey is definitely something to watch. By this time, he’d been doing stand-up comedy for about 20 years and had been attempting to make a career in Hollywood for nearly a decade, and you can feel how hungry he is to make it work. He’s a live wire, never standing still, his movements bouncy and jittery. He’s spent so many years playing angst-ridden characters that it’s almost a surprise to see him back in rubber-face mode, contorting his face and launching into impressions whether there’s a plot-driven reason or not. He commands the screen, tying himself into pretzel knots and bouncing around like a hyperactive 5-year-old. He rolls words around in his mouth, making them just as elastic as his limbs. This isn’t a movie, it’s an audition reel for Carrey, applying for the job of America’s most popular comedian, and the youth of that day gave him the job on the spot.

The camera keeps Carrey in center frame almost the entire time – there are other actors here, most notably a slightly pre-Friends Courteney Cox (that would debut in fall 1994), but they don’t matter. This is Carrey’s show and you can feel him pushing to dominate. He’s a living cartoon and for a second I misremembered the film and thought I should call my kids in to watch it; I’m glad I didn’t, because five minutes into its runtime, the movie delivers its first of many sex gags.

I can’t say whether you think that’s funny or not; humor is subjective. Teenage Chris ate it up, while middle-age Chris was more impressed by the energy displayed than entertained by the result. There’s something to admire about Carrey going all in on this, but it’s also deeply exhausting. Unbridled Jim Carrey is too much (although I’m not fully grown up; I still found the scene of Ace talking to Tone Loc through his ass funny, particularly when he asks if Tone has “a mint, or perhaps some Binaca.”)

Carrey’s films got better once directors understood how to marshal the vulnerability and insecurity of his characters as a counterpoint to the chaos. But Ace is, by design, an unpleasant, annoying character. He picks fights with other detectives, is sexually aggressive toward every woman he meets, spits pumpkin seeds out on a stranger’s desk, verbally accosts his rich host at a dinner party, and calls anyone he doesn’t like a loser. Carrey even said he ramped up some of Ace’s most distasteful elements – particularly his homophobia – to get a reaction that showed he was a real jerk, but the result is that it just makes him more unlikable and less funny.

And listen, I’m not opposed to oafish, flawed comedic characters. Anchorman and Step Brothers are two of my all-time favorite comedies. I love the first Austin Powers movie. You can absolutely have an unlikable, even repellent, character at the center of a comedy and make it work. Some of the best comedies are built around that. But to pull it off, you either need someone even more unlikable that the protagonist is pushing against, or you need him surrounded by likable characters whose mission it is to get him to see the error of his ways. Ron Burgundy overcomes his misogyny; Austin Powers learns to settle down; even the men-child of Step Brothers put childish things aside (but still love their crossbows and Chewbacca masks).

But Ace is not just the center of gravity of this movie; he’s also its only actual character. Every other human being is a prop for Carrey’s comedy. Aside from a few scenes with the real cops who look down on him, Ace is not pushing back against anyone. He’s not Bugs Bunny, as Axel Foley was in Beverly Hills Cop. He’s not outwitting anyone. He’s just going to dinner parties and making fart jokes, jumping into dolphin tanks and doing Captain Kirk impressions, and performing slow-motion instant replay gags at a mental institution because it makes him giggle. Ace was popular with adolescents because he captures that spirit of a young kid who thinks making fart noises at the dinner table makes him the height of entertainment; if ever a movie captures what a middle schooler is like in grown-up skin, it’s this.

And no one pushes back against Ace. Yes, Cox’s character acknowledges that he’s weird and other people look a bit askance at him, but there’s never really any attempt to make him rein in his antics or grow up. By the end of the film – even when he’s physically assaulting a mascot – everyone just rolls their eyes. “Oh that Ace,” they seem to be saying.

Unforgivably mean and gross

And maybe that would just be nothing more than an annoyance if the film weren’t also full of vintage-90s gay panic and transphobia. In one sequence, Ace – trying to track down a Super Bowl ring with a missing stone – stalks members of the 1984 Miami Dolphins, basically annoying them until he can find what he wants. At one point, he stands next to a player at a urinal and looks down to get a look at the ring. The player thinks Ace is looking at his genitals. He doesn’t get mad; he smiles. And Ace gets a repulsed look on his face and walks away, director Tom Shadyac holding the shot long enough to capture the player mincing away effeminately. Because, ho ho, he’s gay and they act so silly. It’s an immature gag, and it’s not even the movie’s worst sin.

The film’s final reveal hinges on the fact that the ball-busting police captain (Sean Young) who’s been berating Ace the entire film – before inexplicably making out with him on her desk – is actually a trans woman who was previously a disgraced football star. Ace first makes this reveal by stripping her down to her bra and panties in front of an entire police force; it’s a humiliating and mean-spirited sequence, played entirely for laughs.

But even meaner and grosser is Ace’s reaction to finding out Young’s character is trans. After he puts the facts together, the film features a long montage of him vomiting repeatedly, lighting his clothes on fire, and having a nervous breakdown in the shower. When the captain points a gun at his head and asks what he would know about stress, Ace says “Well I have kissed a man,” as if it’s the greatest trauma he has ever suffered. It’s deeply offensive – I’d like to assume it was so even in the 1990s, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it was par for the course – and I’m curious what the very openly progressive Carrey would say about it today.

And again, if you squint, you can see how this might be funny if the film handled it well, on par with Ron Burgundy’s sexism, a thing that the film presents as a major character flaw. But nothing in the film suggests that Ace’s revulsion is anything but normal. Once all the cops – and Dan Marino, who has been kidnapped by this point in the film – realize that their boss is a trans woman, they all start vomiting. Even Marino asks Ace for some gum. Ace doesn’t have to reform; instead, they all laud him as a hero, and they’re connected because gross, they kissed a trans person. What an awful final note for any movie to end on (making things worse is the godawful rap Tone Loc does about Ace over the credits).

The film, like I said, was a hit. And to his credit, I think Carrey found better projects and put himself in the hands of better directors as he became a star. I’m not doing this series because I think it’s ridiculous that he was successful; I’m doing it because I think Jim Carrey is funny and a genuinely good performer. I’m excited to see if The Mask holds up from my last viewing (also about 25 years ago), and I still quote Dumb and Dumber on the reg. And if I recall correctly, the Ace Ventura sequel dialed back on this one’s most worst impulses and works a lot better.

But, oof, Ace Ventura: Pet Detective is proof that you can’t be a kid again…and maybe you should be glad for that.

Now in theaters

Over at Michigan Sports and Entertainment, you can read my thoughts on Argylle, the latest spy caper from director Matthew Vaughn. I didn’t hate it as much as some critics do, but it’s definitely a mess. Also, you can read what I think about the newest trailer for Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire.