When it comes to box office trivia, the question of the highest-grossing movie of 1984 always throws me for a loop. Surely, I think, it must be Ghostbusters, which opened that summer and was a cultural phenomenon. And yes, Ghostbusters did very well, dominating the #1 spot for seven straight weeks and raking in $229 million.

But the highest-grossing movie of that year is actually the Eddie Murphy action-comedy Beverly Hills Cop, which dropped in December and held the top spot at the box office for a staggering 13 weeks – a streak that wouldn’t be broken until Titanic debuted in 1997. The Martin Brest comedy brought in $234 million – just edging out the Ghostbusters total and cementing its place as the highest-grossing release of 1984 and, adjusted for inflation, still up with The Exorcist and The Godfather as one of the top-grossing R-rated films of all time.

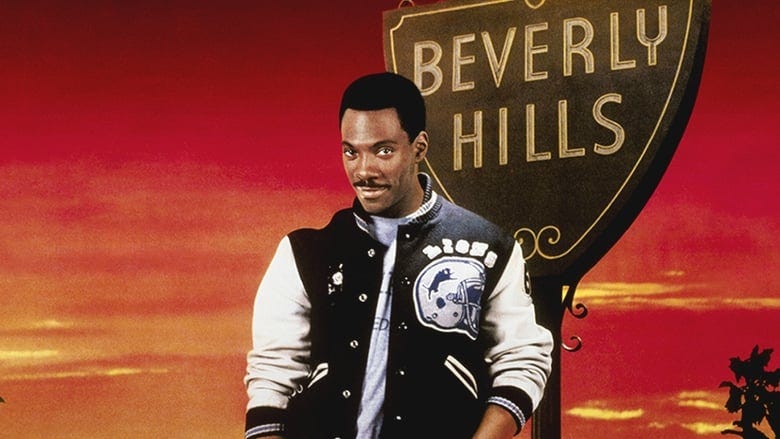

I was only 5 years old when Beverly Hills Cop was released, and I didn’t end up seeing it until late in my teens or early twenties. Even so, it had such a cultural impact that you couldn’t help but absorb it by osmosis. My mom had a Mumford High T-shirt. Glenn Frey’s “The Heat is On” was all over the radio. When our first Blockbuster Video opened, one of the first posters to catch my eye was Murphy leaning against the Beverly Hills sign in a promotion for its sequel. But I’ll confess that I didn’t pay much attention to Murphy until The Nutty Professor, by which point all three Beverly Hills Cop movies had come and gone.

But everything old is new again, and later this year, Netflix will bring Murphy’s most iconic character out of retirement for Beverly Hills Cop: Axel F. That, coupled with the fact that later this year will see the 40th anniversary for the original – and, to a much, much lesser extent, the 30th anniversary of Beverly Hills Cop III – made it an ideal choice to jump back into my monthly Franchise Friday series.

So, don your Detroit Lions jacket and crank up that Harold Faltermeyer score – the heat is on.

Beverly Hills Cop (1984)

My initial – and, prior to this – only viewing of Beverly Hills Cop was about 20 years ago, and I remember not being overly impressed. It struck me as a typical action comedy, and I think I even walked away thinking Eddie Murphy was a bit lackluster. It was fine, but it never captivated me the way, say, Lethal Weapon did.

About twenty years later, I can understand why the cop story didn’t capture my attention, but I can safely tut-tut my younger self for his criticisms of Murphy’s star-making performance.

On paper, Beverly Hills Cop is a fairly generic action-comedy. The script is a formulaic culture clash about a detective from Detroit who heads to the chic California community when his friend is gunned down. It’s the typical comedic fodder you’d expect – eyebrows raised at the garish wealth and strange proclivities of the uber-rich – and the police elements are fairly standard, boiling down to a story about an art gallery owner smuggling drugs and bonds and being easily tracked down. It doesn’t have the edge and pulpiness of, say, Lethal Weapon or the grit and racial provocations of 48 Hours. On paper, it’s a generic buddy cop thriller and you could, in theory, swap out any actor to play Axel Foley (famously, the script started as a vehicle for Sylvester Stallone).

But they didn’t get any other actor; they got Eddie Murphy.

You can feel the hunger in Murphy’s performance, coupled with the confidence that made him an instant hit on Saturday Night Live at age 19. This was, of course, not Murphy’s first big-screen performance. He stole 48 Hours out from under Nick Nolte two years earlier and teamed with Dan Aykroyd to great effect in John Landis’ Trading Places. But this was Murphy’s first leading vehicle, and you can feel the energy crackling around him in every scene as he ascends to stardom before your eyes.

When I was younger, I viewed Axel Foley as a slightly lethargic Murphy character. I think what I overlooked was that Eddie’s not doing shtick; he’s giving a performance. Axel Foley isn’t a cartoon (yet); he’s an upstart trying to prove himself and avenge his dead friend. Axel’s funny, yes, but he’s also smart and a damn good detective. Many of the laughs come from him outwitting everyone else around him. I also appreciate that Axel just comes off as a likable guy. When his friend shows up at his apartment in Detroit, there’s real warmth and affection – the victim is not just cannon fodder. Likewise, Axel’s partnership with an old friend who works at the art gallery (Lisa Elibacher) is also warm. Jenny’s an old pal of Axel’s, and the film gives them a relationship that feels like buddies looking out for each other. It never tries to make Jenny a sexpot or love interest, and she’s a smart, helpful sidekick. It helps the film feel textured, giving it a grounding that Murphy can then bounce off.

And boy, does he bounce. I’m far from the first person to equate Axel Foley with Bugs Bunny, but it’s really the best comparison. It’s a joy to watch Murphy walk in and be smarter than everyone else in the room, weaving outlandish lies and annoying everyone with a smile so big that you can’t help but love him. It’s a great, fun performance, and the best part is how likable Murphy is even when the shtick is dialed back. Yes, the banana in the tailpipe is funny, and Eddie has a lot of fun as Axel convinces a hotel clerk that he’s a writer with Rolling Stone. But Murphy’s also just great to watch when Axel strikes up a friendship with Beverly Hills detectives Taggart (John Ashton) and Rosewood (Judge Reinhold). There’s chemistry between the three when Axel coaxes them to a strip bar or as Rosewood finds himself willing to put his own job in jeopardy to help Axel.

A few years after Beverly Hills Cop, director Martin Brest would direct one of the best buddy comedies of the 1980s with Midnight Run. His sensibilities help keep Beverly Hills Cop moving, even in the rare moments where Murphy’s mouth isn’t running. Brest knows how to film competent action sequences – there’s nothing genre-defining, but the film’s opening chase and final shootout are both fun – and he knows just when to step back and let his cast interact to keep the comedy flowing without becoming too shtick-dependent (I do wish Brest had dialed back the film’s homophobic content a bit).

Brest also understood the power of a good cast. Yes, Murphy’s the star and his performance is the film’s center of gravity. But Ashton and Reinhold know just how to navigate the push and pull with the funnyman, and the buddy dynamics between the three are the strongest part of this film and its first sequel. Breaking Bad’s Jonathan Banks is fantastically scuzzy as the film’s killer. Real-life Detroit police officer Gill Hill is iconic as Foley’s tough-as-nails superior. And even the bit parts bring the funny; Bronson Pinchot has one scene in the film as a flamboyant gallery manager, and it’s possibly the most entertaining scene in the movie.

And, of course, you can’t talk about Beverly Hills Cop without mentioning the producing powerhouse of Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer. This was the duo’s second film, after Flashdance the year prior, and the template is definitely set. There’s the opening montage set to a pop song – Glenn Frey’s “The Heat is On” – the hyper-saturated cinematography, the multiple montages, and the freeze-frame-ending. Beverly Hills Cop plays right into the team’s high-concept playbook. Powering it all is Harold Faltemeyer’s iconic score, and that “Axel F” track does a lot of the heavy lifting for this film and its sequels.

The film was, as I stated earlier, a gigantic hit that catapulted Murphy as well as Simpson/Bruckheimer into the stratosphere. The producing team would perfect its high-concept strategy with the next year’s flashy and totally empty Top Gun – a movie that would have a major influence on Axel Foley’s next adventure.

Beverly Hills Cop II (1987)

The first scene in Beverly Hills Cop II sets the tone for the entire movie.

A gang of robbers hits an upscale Beverly Hills jewelry store, storming in with guns drawn, firing warning shots throughout the location as the editing cuts rapidly. The music is pulsing and loud, the colors popping. As the bandits leave, they shoot up all the glass displays and windows; their leader shoots down a crystal chandelier, which smashes on the ground. There’s no reason for the wanton destruction except that it looks really cool.

Flashy vapidity was director Tony Scott’s calling card. It made Top Gun a generation-defining hit, even though it’s less a movie than a two-hour commercial for the U.S. Navy and Ray Bans. And according to Nick de Semlyen’s Wild and Crazy Guys, when Murphy saw that film, he told Scott to make him look as good as he made Tom Cruise look playing beach volleyball.

And from the first scene, Scott does just that. Axel Foley is no longer an underdog. When we meet him, he’s donning a flashy suit and driving a Ferrari. He’s undercover, but the entire opening act of this film screams that Murphy wanted to look good and be stylish in this sequel. Charitably, we could say that Axel Foley just never let go of the taste of his Beverly Hills lifestyle – the first thing he does when he gets to the city is find a way to commandeer a luxurious home for himself.

It’s a miscalculation. Bugs Bunny is funny when he’s outsmarting people who look down on and underestimate him. If Bugs had the power from the get go, he’d wouldn’t be funny. And it’s the same with Axel Foley. Oh, Murphy still has charm and charisma to spare, and it’s impossible not to laugh at his throwaway lines or get a charge when he flashes that giant smile and lets that deep laugh bellow. But the film constantly sees Axel pulling things over on people who don’t deserve it, and his clever lies from the first film grow into all-encompassing shtick.

Take the way he secures a house for himself upon arrival in Beverly Hills. He finds a fancy home being renovated and then tells the contractors they made a big error and should all head home for the week while it’s being addressed. He puts the jobs of a group of contractors at risk and steals a home just to avoid renting a hotel; it’s not endearing behavior, it’s the work of an asshole. Later in the film, when the new chief of police storms and asks why Foley is looking at evidence, he creates a psychic character that feels less in line with the reality of the movie and more at home on SNL. The big moments are not funny; they’re annoying and Axel is obnoxious without something to push against.

In interviews, actors have said that most of the scenes with Murphy were improvised, and it’s easy to believe. Scott was not known for his comedic sensibilities – it’s kind of weird he was hired to direct this – and I can see how the easiest thinking was to let Eddie do his thing. But a comedian off the leash isn’t always a great idea, and without a good script to push back against, Murphy can be grating.

But originality wasn’t on the table. Initially, the idea was to have Foley head to Europe to crack a case in London and Paris, but Murphy didn’t want to leave the country. And what Simpson/Bruckheimer decided was best was just to rehash the first film. Beverly Hills Cop II follows its predecessor’s template, beat for beat. It opens with Axel on a case in Detroit; Then, a friend – this time, Ronny Cox’s Cpt. Bogomil from the first film – is shot. Alex defies his superior’s orders and heads to Detroit. He’s called on the carpet for making a mess of things, but with Taggart and Rosewood by his side, he busts the bad guy. Cue “Axel F,” cut to the freeze frame, it’s a typical ‘80s sequel that just plays the hits.

It’s not a good movie, but it is sometimes an enjoyable mess. Scott may have directed a lot of empty films, but he made the soullessness look good. The soundtrack pumps, the gunshots blister the eardrums, cars crash and things blow up. Scott was a very good action director, and Beverly Hills Cop II works best as a stupid-but-fun action film. Perhaps leaning into the common knowledge that Foley could have been played by Stallone, the film doubles down on references, turning Rosewood into a gun fetishist with posters of Rambo and Cobra on his walls (even funnier because Stallone wrote Cobra based on rejected ideas he had for Beverly Hills Cop). After Rosewood disposes of bad guys with a rocket launcher, Taggart grumbles “F*** Rambo.” (The film’s villain is played by Stallone’s soon-to-be-ex Brigitte Nielsen).

And there are moments where the film dials back the shtick and just lets Murphy hang out with Ashton and Reinhold. And in those moments, the camaraderie and warmth of the first film return. My favorite scene is actually a throwaway moment where the three head back to Rosewood’s apartment and discover that not only is he a wannabe Dirty Harry, but that he’s also got a thing for plants. It’s the playfulness of the three leads that makes those scenes work, and it’s a reminder that Brest was really good at having that deft hand with his actors, while Scott seemed just to treat them as models.

But that Simpson/Bruckheimer magic also carries the film. Their love of deep oranges and blues, underscored by a hit pop soundtrack, carries over from Top Gun and turns the film into a sleek and flashy bit of entertainment. Paul Reiser gets a bit more to do as Foley’s partner back in the Motor City – and while he’s not overly funny, he does do an impression of Gill Hill that makes me laugh. And it’s worth noting that I love the scenes set in Detroit; they have a grittiness that speaks to really filming in the city, and it gives Axel a grounding that the rest of the film misses. And, as with the first film, that “Axel F” track elevates every single scene.

Beverly Hills Cop II can never recapture the spark of the first film, and it’s a totally disposable laundry folder of a movie. But it has its moments, and I understand why it has its fans.

And next to the third film, it looks like Die Hard.

Beverly Hills Cop III (1994)

On social media, I described watching this trilogy as the cinematic equivalent of watching a balloon deflate. The first film has energy and wit. In the second, the spark’s a bit gone, but you can see remnants of what made the series so appealing.

Beverly Hills Cop III is a saliva-soaked raspberry to anyone who ever enjoyed Axel Foley.

This was supposed to be Eddie’s comeback after a run of stinkers including Harlem Nights, Another 48 Hours, Boomerang and The Distinguished Gentleman. Murphy was supposed to flash that smile and charm us all again as Axel Foley. Instead, it was his biggest misfire yet, failing to recoup its $120 million budget and sitting at a wretched 11% on Rotten Tomatoes (the next year would bring another failure for Murphy, with Vampire in Brooklyn, before he made his first of many start-and-stop comebacks with The Nutty Professor). It killed the franchise for 30 years.

The third Axel Foley adventure is a lifeless, laugh-less, pulse-less affair, so inert and directionless that it’s hard to believe it wasn’t released straight to video. Writer Steven De Souza was brought in to make “Die Hard in a theme park,” but budget cuts kept that vision from becoming a reality (side note: as a teenager, I once wanted to write a movie that was basically Die Hard in a theme park, so I’m really irked that never came to pass). Simpson and Bruckheimer bailed on this one, and their slick sheen and knack for surface pleasures is completely absent, meaning even the guilty pleasures of the franchise are nowhere to be found.

The setup is the same: Axel returns to Beverly Hills to investigate the shooting of a friend (this time, it’s Hill’s Inspector Todd). He learns that the killer has a connection to the theme park Wonder World, and he heads to California, once again teaming with Rosewood – although Taggart has long since retired to California, and he’s replaced by a bland proxy, played by Hector Elizondo.

The first Beverly Hills Cop succeeded because Martin Brest had a knack for marrying action with character-driven comedy. Beverly Hills Cop II pulled in an action director; the comedy languished, but the shootouts were fun. For Beverly Hills Cop III, they brought in John Landis, who, by this point in his career, could neither direct effective action nor comedy.

It’s a shame to type that sentence, because in the early ‘80s, few directors had as firm a handle on genre, especially when it came to throwing some comedy into the mix. An American Werewolf in London is one of the great horror comedies of all time. The Blues Brothers is a combination of action, music and comedy that works despite being held together by spit and bubble gum. And Landis had worked on two of Murphy’s biggest hits – Trading Places and Coming to America. But the two had a falling out on the latter, with their relationship becoming so acrimonious that Murphy once said Landis had a better chance of reteaming with Vic Morrow – the actor tragically killed in an accident on the set of Landis’ Twilight Zone: The Movie segment – than with him.

One could see how bringing Landis in could, in theory, help restore the balance between action and comedy that had been lost with the second installment. But Landis whiffs on both accounts. The action is lackluster; there are a few uninspired shootouts and one amusement park ride rescue that is hampered by some truly awful green screen work. There’s a final action sequence on the park midway that is just a collection of gags as Axel wields a prototype firearm that also plays Jerry Lewis songs (ho, ho!), and a final stalk through a prehistoric dark ride that lacks any energy or suspense.

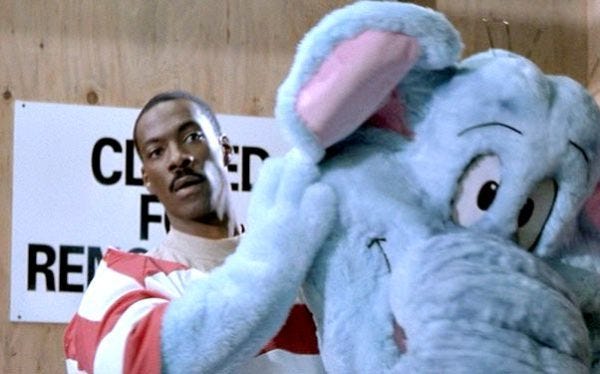

But the comedy doesn’t work either. Landis comes from very sight-gag oriented comedy, and his version of a joke is to go big with visual jokes…something at odds with a series where the humor came from watching Foley motormouth his way around everyone else. The film opens with thieves in a chop shop doing a dance number to The Supremes. Axel doesn’t really push against Beverly Hills culture; he sits slack-jawed as an automated parking system makes dumb jokes about homeless people. When Axel tries to save two kids on that amusement park ride, Landis cuts multiple times to shots of mascots staring up in terror. It’s humor aimed at 12-year-olds, but in a movie sprinkled with bloody shootouts and F-bombs. It never works; it’s dead on arrival.

Murphy has been described as depressed on the set, and Landis reported that he initially wanted to cut any wisecracks, since Axel was “a grown man now.” And while I don’t know how true that is – Axel’s smart mouth is still in play, and he flashes that smile – Murphy’s silliness seems forced. At one point, Axel escapes some bad guys by walking across a stage and doing a silly dance with costumed characters, but it’s not particularly funny. Gone is Axel trying to push against the uptight Beverly Hills citizens and cops; now he’s just a regular action hero who occasionally makes wisecracks. Rosewood’s love of authority is taken to Police Academy lengths – not a compliment – and Elizondo plays his grumpiness too broad. The fun chemistry between Taggart, Rosewood and Foley is gone; the dynamic is off. Even Paul Reiser is nowhere to be seen (and while I know the opening sequences were filmed in Detroit, it feels like; it could be filmed in any nondescript L.A. back alley).

There’s nothing to Beverly Hills Cop III. It’s a slog, with neither good jokes nor good action. Even the “Axel F” theme feels obligatory (and, at one point, it even is presented as a cartoon theme). The one spark comes from the return of Bronson Pinchot’s Serge, but even that feels like a last-ditch effort to capitalize on Pinchot’s “Perfect Strangers” fame, and the joke is hammered into the ground. It’s easy to see why Murphy hung up the badge after this (well, for three decades).

We’ll see if there’s any spark left for the fourth installment later this year. Murphy makes surprising comebacks…he also knows how to squander them. We’ll check in again with Axel Foley this summer.