A week or so back, the Vatican announced its mascot for the 2025 Year of Jubilee, a young anime-inspired character named Luce. As with most attempts to mix Christianity and pop culture, it was controversial, with some people decrying its irreverence, others liking the attempts to draw in youth, and some saying it was demonic because, of course, that’s a go-to shutdown. Not being Catholic, I don’t have a dog in the fight, although I’m not the first to think it looks like Coraline got religion.

What I did think, however, was how the young icon reminded me of another attempt to blend pop culture and religion. I’m talking of Buddy Christ, from Kevin Smith’s comedy Dogma. And Smith caught it as well. And it made me laugh, because I’m an outspoken fan of Smith’s movie, which turns 25 this month.

As a follower of Christ, it might seem odd that I love this gag. And yet, Buddy Christ always makes me laugh. It’s not just because I’m a fan of Dogma (although I am). It’s that this joke both helps me recognize my own idolatry and laugh at my hypocrisy.

Doesn’t it pop?

Dogma, released in 1999, follows two fallen angels who try to exploit a loophole in Catholic theology that will allow them to enter Heaven. The problem? Doing so will negate the will of God and unravel existence. The film weaves poop jokes and f-bombs alongside convoluted theological discussions. Its cast includes Linda Fiorentino, Ben Affleck, Matt Damon, Chris Rock and Alan Rickman. It only brought in $30M at the U.S. box office but, like most of Smith’s comedies, has a considerable cult following. I consider it Smith’s most ambitious and funniest film.

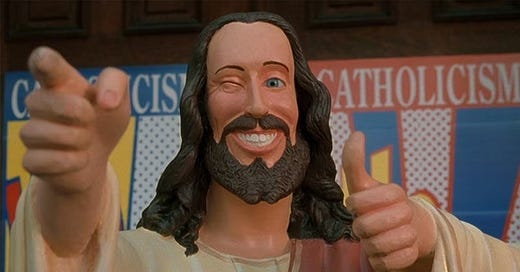

The Buddy Christ isn’t even a major part of the film, but it’s easily its most memorable moment. It shows up once, in a press conference that the cardinal at a New Jersey church hosts to announce the church’s rebranding. Festooned behind him are comic book-style posters that declare “Catholicism Wow!” The cardinal, played by George Carlin, bemoans that too many feel the church is aloof, and symbols like the crucifix are “wholly depressing.”

To usher in a new, fun Catholic Church, the Cardinal unveils the Buddy Christ, which features Jesus with a cartoon grin, shooting finger guns at the crowd. Music swells and people applaud. The movie doesn’t mention it again, but I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it.

The (Buddy) Christ we want

Smith isn’t subtle about the joke. The Buddy Christ is created as a way to lean away from aspects of the faith that turn people away. While Jesus’ teachings were of love and compassion, Christianity is also full of stories of sacrifice, suffering, crucifixion and martyrdom. That doesn’t market too well. Even Jesus knew this when most of his followers left after being told to drink his blood and eat his flesh. If a church wants its key demographic to stick around, it’s tempting to trash the gruesome stuff and focus on the positive. “Christ didn’t come to give us the willies; he came to help us out,” the Cardinal says.

Crucifixions, martyrdom and sacrifice aren’t as attractive as a God who works like a vending machine, promises easy answers and gives us a thumbs up. It’s nice to think about, but it’s not the story the Bible tells. You can try to market church without the grimness, but it’s not going to be Jesus. Even Smith’s film, filled with one-liners, finds that following its tangents leads to violence and bloodshed. The Bible isn’t safe for the whole family.

But I have to admit that cheerleader Jesus is appealing. I know Smith didn’t intend the film as anything more than a lighthearted skewering of theology, but the Buddy Christ actually serves as a very visual rebuke to my baser instincts. It’s a reminder that I often want a Christ in my own image, who only wants to massage my ego, give me an attaboy and tell me “you’re doing great, champ.” It’s inconvenient to remember Christ’s calling to pick up our own cross, turn the other cheek and consider others to be more important than ourselves. A five-second gag in a raunchy comedy has turned into a tool that helps me identify my own idols.

Laughing at ourselves

Of course, many Christians weren’t laughing in 1999. Dogma was condemned and protested by many in the Catholic church upon its release. I’m Protestant, and I don’t recall the uproar being as great in our community, but that was probably because most evangelicals believed that R-rated comedies were off limits. Which is a shame. Dogma is not for everyone, but I think Smith’s film, while irreverent, is a sincere conversation about faith and the foolishness humans get into when they try to put the infinite in a box.

The Buddy Christ is just one funny joke about our attempts to shape the gospel story into something more palatable. The film also has fun discussing the weird theological nuances of Catholicism, the superpowers that come with the ability to bless, and whether angels have genitals. The joke is never on God but on humans who’ve created a labyrinthine system to keep power and explain away the inexplicable. The film takes its messages of redemption and faith seriously. There’s also a conversation between Damon and Affleck that strips away all the jokes and delves into a discussion about God’s patience and human sinfulness (warning, R-rated language). Not bad for a movie that also features a poop demon.

I think there’s a necessity to art that helps show Christians their own foolishness. We need to be able to laugh at ourselves, and we need to understand that the watching world sees our hypocrisy. Not every movie that deals with faith can be a Buddy Christ flashing us a smile and a thumbs up. Sometimes we need to be able to recognize and laugh at our own failures before discussing how to move on. Movies like Life of Brian, Saved! and Dogma helps me see how short I fall in living out Christ’s message. And it does that not with the thump of a Bible but with some clever jokes.