Was Scrooge's redemption always a sure thing?

'The Man Who Invented Christmas' is a frothy story about creating a classic.

On the Wednesdays leading up to Christmas, Chrisicisms will take a look at various film adaptations of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

Few stories have seeped their way into culture as deeply as A Christmas Carol. Since its publication in 1843, it’s become a beloved redemption tale, and its characters have been portrayed on screen by everyone from Alistair Sim and George C. Scott to Bill Murray and Kermit the Frog.

It’s a story that serves as shorthand for many modern Christmas tales, the go-to template for sitcom episodes and animated specials. Scrooge’s journey from miser to philanthropist is so well-trod that we know the beats by heart and are able to recite lines verbatim. It’s as much a tradition as “Deck the Halls,” and retains its transformative power over a century and a half later. We continue telling Ebenezer Scrooge’s story because it still resonates.

The Man Who Invented Christmas tells the story behind the creation of this yuletide classic. And while Bharat Nalluri’s film can’t compete with the real thing, it does remind us what makes it so powerful.

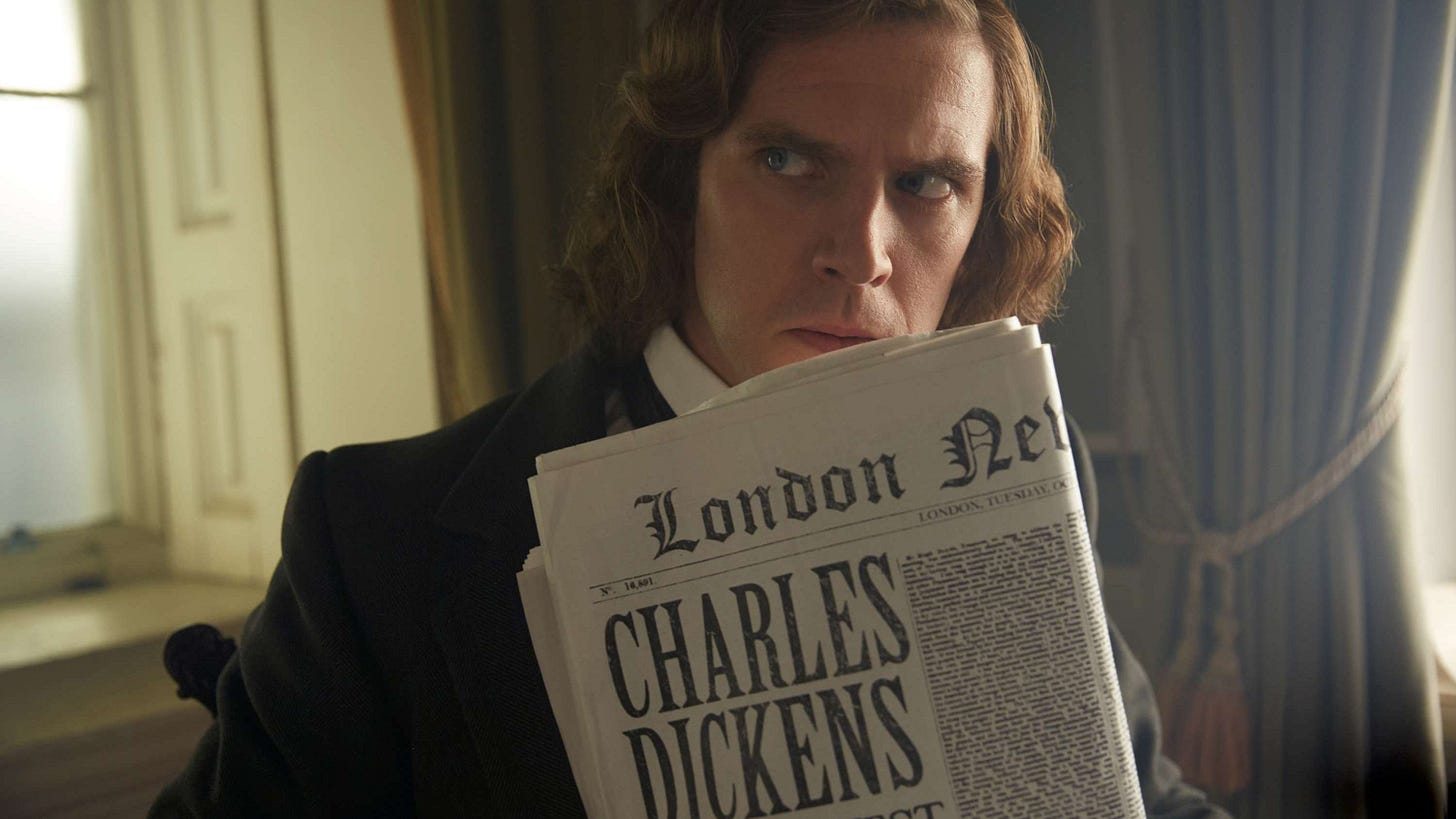

In late 1843, Charles Dickens (Dan Stevens) is in a slump. After the adulation that followed Oliver Twist, he’s endured three straight flops, is in debt and expecting another child. He’s outraged by the treatment of London’s poor and fascinated by his housekeeper’s stories about Christmas in Ireland. In a fit of desperation, inspiration and outrage, he agrees to self-publish a Christmas novella, despite the fact that the holiday is waning in popularity, he doesn’t have an idea and he needs to finish it in six weeks.

The Man Who Invented Christmas pays lip service to the holiday’s decline and relegates Dickens’ role in its revitalization to a title card at the very end. While there’s likely a compelling, rich and dramatic story about the historical context of A Christmas Carol and Dickens’ contribution to how we view the holiday today — the film gets its title from Les Standiford’s meticulously researched book of the same name — Nalluri is more content to tell a Shakespeare in Love-style light drama where lines of dialogue and characters from the novel are inspired by Dickens’ walks through London and interactions with fellow citizens. Those looking for a gritty, realistic take about the plight of the needy in Victorian England may want to look elsewhere; Nalluri’s film is a frothy lark.

That’s not a bad thing. Stevens is all nervous energy and clumsy jitters as Dickens, who engages in loquacious and sometimes heated banter with his characters, most notably Scrooge (Christopher Plummer). Much of the film involves Dickens trying to figure out where the story is going by arguing with his characters and trying to force the story into shape. Given that writing is second only to computer programming as the most boring thing to watch on screen, this gives the film a jolt of energy and renders that task of storytelling more dynamic than usual.

It also allows Nalluri to sneak in a retelling of A Christmas Carol in a way that doesn’t feel pat or overly familiar. We’re so familiar with the story — Marley, the ghosts, the possible death of Tiny Tim — that it’s easy to forget that at its heart is a question that will be ever-relevant: Can bad men change?

The key is that Dickens isn’t sure. He’s convinced that his ghost story will end with Scrooge’s destruction and the death of Tiny Tim. He’s resistant to the idea that his grotesque creation can be redeemed,likely due to the fact that he’s seen his own father (Jonathan Pryce) screw up time and again. Dickens’ own past is filled with abuse at the hands of those who exploited him and he has his own axe to grind, even as those around him tell him his story only works with the redemption of Scrooge.

When it works best, The Man Who Invented Christmas is an effective look at the way characters serve as their writers’ angels and demons, and an insightful story about how creativity transforms artists and helps them form their outlooks. Less that sound pretentious, rest assured that Nalluri tells it with warmth and humor and his cast is charismatic; it may be more saccharine than necessary but its energy keeps it from drowning in self-serious, suffering artist cliché.

Is it an oversimplification of how Dickens created his most beloved story? Probably. And there’s likely a richer, deeper and more artistic take on this story to be told. But as a reminder of the rich power of Dickens’ classic and a warm-hearted entry into the holiday canon, The Man Who Invented Christmas is far from a humbug.