The Slasher Series: Halloween (1978)

Looking back at some slasher icons starts with our introduction to Michael Myers.

A few years back, I published a series of Halloween-related articles about the first appearances of iconic movie slashers. That site is no longer around, but I enjoyed the articles that came out of it, so as a special October treat, I’m going to re-publish one a week until Halloween.

I met him 15 years ago. I was told there was nothing left; no reason, no conscience, no understanding in even the most rudimentary sense of life or death, of good or evil, right or wrong. I met this six-year-old child with this blank, pale, emotionless face, and the blackest eyes - the Devil's eyes.

More than 40 years from Halloween, as we approach a sequel to yet another reboot, why do we keep telling stories about Michael Myers? It’s not the quality of the films; of the 10 movies to feature Myers (not counting this year’s sequel), only one or two could genuinely be called good. It’s not the inventiveness of his kills; Myers is brutal, but he has nothing on Jason Voorhees in that department. And it’s not the mythology, as any attempts to explain Myers’ motivations (cough, druids, cough) have only made the series laughable.

No, the power of Michael Myers is rooted in psychiatrist Loomis’ description of him above. Myers is evil, he is beyond explanation, and he cannot be stopped.

A terrifying tale

The slasher movies that glutted cinemas in the 1980s don’t have a reputation for being great art. They were often cheaply made trash featuring nubile actresses running from masked killers, stopping only to smoke weed and have sex. They were boobs-and-blood delivery systems, and they were everywhere. Listen to the making-of documentaries about A Nightmare on Elm Street or Friday the 13th, and the cast and crew knew exactly what they were making; often, the audiences also knew exactly what they were seeing.

But no one saw Halloween coming. It was the film that arguably kick-started the slasher movie craze (credit can also be given to Psycho and Black Christmas), made by a no-name director and a cast composed of largely unknowns. Even the people who made the film expected it to be bad, or at least forgettable.

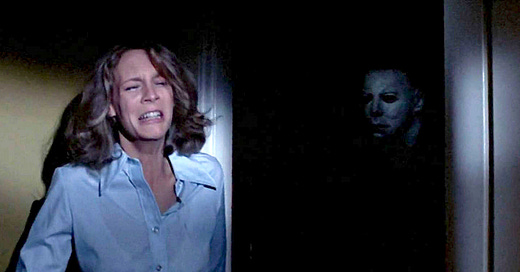

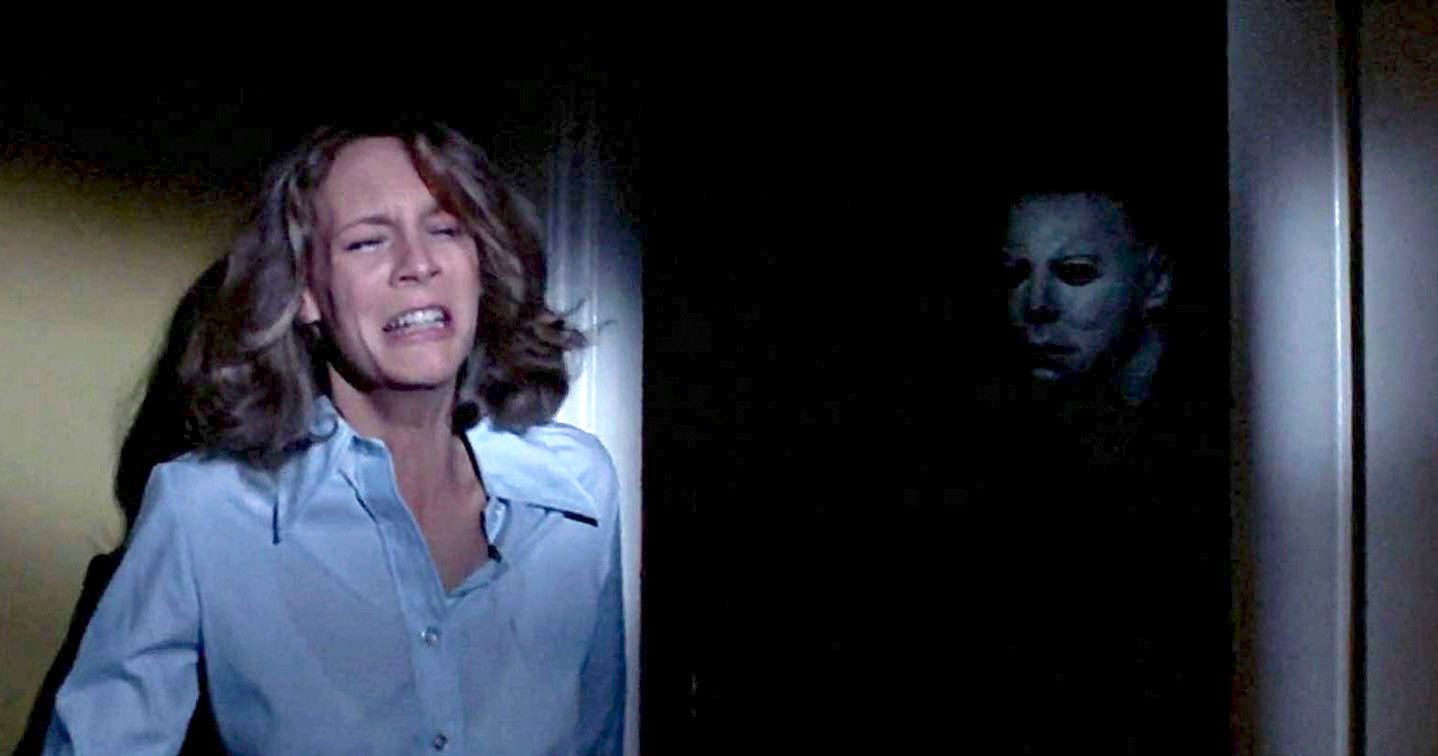

It’s understandable: Halloween’s plot is as basic as it gets. Fifteen years after a murder that put him away in an asylum, Michael Myers escapes and returns to his hometown of Haddonfield. He crosses paths with high schooler Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) and her friends, and he picks them off one by one over the course of the night while psychiatrist Dr. Loomis (Donald Pleasance) tries to apprehend him. Roger Ebert referred to slasher films as “dead teenager movies,” and that pretty much sums up Halloween’s story.

And yet, Halloween isn’t disposable. Not only did it kickstart an entire genre — one that, with Happy Death Day, Freaky, Fear Street and next week’s Halloween Kills, is seeing a resurgence — but it also stands apart from its imitators by being a good, arguably great, film.

A horror master

Halloween wasn’t Carpenter’s debut — he’d previously helmed the little-seen sci-fi comedy Dark Star and Assault on Precinct 13 — but you could see hallmarks from his earlier efforts begin to take root. Before the narrative begins, Carpenter’s synth-laden theme pounds over the opening credits. As the camera zooms onto the face of a grinning Jack-O-Lantern, the score strikes an unnerving vibe, and drives the suspense throughout the film.

Halloween is fairly non-bloody. Myers strikes in the shadows, quickly and silently, and the gruesome aftermath is left to our imagination. Instead, the scares come through Carpenter’s skill at crafting tense sequences and setting our nerves on edge. Myers pops up at the edge of frame, stands still and silent just just outside a window or down the street, and then disappears. The film is patient, playing with our nerves instead of rushing to deliver shocks.

Carpenter was influenced by the films of Alfred Hitchcock, and Halloween owes a large debt to the director’s skill with a camera. Carpenter uses long tracking shots, beginning with the film’s opening, in which we watch a juvenile Michael commit his first murder from his point of view. Carpenter ably directs where the camera is at, how it moves — often never stopping, mirroring Myers’ shark-like drive — and what we see. Right out of the gate, Carpenter knows how to craft a scare; a sequence late in the film where Laurie stops by an open doorway to catch her breath, only for Michael to slowly emerge from that shadows, still terrifies.

I’ve seen Halloween perhaps a dozen times, but this was the first viewing where I noticed how Carpenter’s skill with geography increases the tension. Early in the film, he walks us through the neighborhood with Laurie and her friends, helping us gain our bearings. Later, when Laurie is dropped off at her babysitting gig by Annie, Carpenter makes sure we see that the two girls are working across the street from each other. Later, as Myers stalks and kills Annie and other teenagers in one house, Carpenter cuts to views out the window in the other, as children glimpse Myers stalking around. This pays off in the film’s climax as Laurie, who’s discovered her friends’ corpses, flees to the home where she’s working, Michael only a few steps behind her. Throughout the film, we always know right where Myers is in proximity to his victims, keeping us aware of the quickly closing distance between predator and prey, drawing Laurie closer to her fate.

Slasher films, because of their rushed productions, low budgets and amateur cast, often struggle to make their protagonists feel like anything other than dead meat. In Halloween, however, we’re given the first — and, perhaps, most iconic — Final Girl. Curtis’ contribution to the film’s success can’t be overstated. Laurie is smart and likable, with a vulnerable streak that earns our sympathies even before she’s in mortal danger; a telephone conversation where Annie tries to set Laurie up wither her crush gives Curtis a chance to play shy, making the audience feel more protective toward her. If Laurie is too unsure to say “yes” to a Homecoming date, how will she survive a duel with a monster? The answer, of course, is that Laurie also has survival instincts that she’s unaware of, and turns into a genuine foil for Myers. Carpenter had been enamored by the work of Curtis’ mother Janet Leigh in Psycho and A Touch of Evil; he was likely unaware he was given an equally great actress her big break.

She’s not alone, although Loomis doesn’t show up to her defense until the very end. He’s a haunted man, driven to abandon his ethics to keep Michael locked up — when we meet him, his plan is to drug the killer to ensure he never leaves the sanitarium. Loomis is haunted by Myers; he believes he’s a being of pure evil. But Pleasance never plays him like a madman; he’s smart and rational, which means his cautions never come off as rants, but carry the chill of plausibility. And they should — after all, Laurie and Loomis are up against the Boogeyman.

Icon of fear

If there was a horror Mount Rushmore, right alongside the hockey mask-clad face of Jason and the burned visage of Freddy Krueger, you’d have Michael Myers. For 40 years and 10 films, he’s terrified the babysitters of Haddonfield, stalking the suburban streets on Oct. 31 with nothing more than his mask and a butcher knife.

The thing is, there’s nothing immediately terrifying about Myers. He lacks the hulking, Terminator-esque menace of Jason. And — at least in this film — there’s nothing supernatural about him. Heck, even the diminutive Chucky is probably scarier on the surface than this lanky, average-looking white dude.

But there’s that mask.

The bleached-out, distorted mask makes Michael Myers an icon. It’s not a monster mask; we can see the eyes, the mouth, even a tuft of brown hair. But we can’t call it human, either. It’s too pale and placid, no emotion registering in the dark eyes, no clue as to whether Myers is resting or staring us down. It’s uncanny, straddling the line between what’s supernatural and what’s familiar.

In the end, it’s just evil.

It’s the best way to capture whatever there is to Myers’ personality. He’s not driven by anger or revenge. He started killing when he was a kid, seemingly just because. He has no remorse; he chooses his victims not because they’ve wronged him but because they’ve crossed his path (let’s ignore what Halloween II says). He’s human enough to bait his victims, but detached enough from any type of morality that he’ll admire his handiwork after he stabs a man to a wall. He shows up and, if you’re in his path, you die. It’s that wicked, it’s that simple.

That’s the kind of horror that survives for 40 years.

Evil can’t be contained

The true horror of Halloween, however, isn’t that Michael Myers stalks these teenagers. It’s that he can’t be stopped. Sure, maybe Laurie escapes and Loomis puts an end to this particular killing spree. But the film’s final moments are perhaps Halloween’s most effective.

Loomis, who has been pursuing Michael, hoping to stop him, shows up at just the right time. He shoots Myers several times, causing the killer to plunge two stories to the lawn below. Laurie, finally able to stop, breaks down in tears. Loomis walks to the window; Myers is gone. As Carpenter shows us the film’s locations one last time, that husky, masked breathing fills the screen. Myers isn’t dead; he is out in the world.

I’ll admit that, in most viewings, I’ve given Loomis short shrift. He’s not an overly effective character. He’s mainly an exposition machine, delivering portentous musings and contributing to Myers’ legend. While most of the characters are being murdered, Loomis is camping out at Michael’s house, several blocks away. It’s only dumb luck that he eventually sees the stolen car that brought the killer home to Haddonfield. He’s not a great hero.

But is he supposed to be? Perhaps the most effective use of Loomis is to convey his impotence, the frustration of being the one rational person to know that evil is coming and unable to convince anyone or to stop it.

“I spent eight years trying to reach [Michael] and then another seven trying to keep him locked up,” Loomis says at one point. His greatest goal in life is to keep Myers from being unleashed on society. And when he has a chance to finally put him in the grave, even that action is for naught. The evil can’t be contained. Michael will walk the streets and people will die.

To me, that’s more terrifying than any violent deaths or suspenseful chases. Our great hope is that the world is a rational place, that the scales of the universe eventually tilt toward justice. These days, though, I often wonder if that’s the case. We all want to believe that, when push comes to shove, good wins. Our greatest fear, the one we don’t speak, is that maybe it doesn’t. Halloween exploits that. And as I watched this film, particularly as the news focuses on a world that seems to have lost all sense of rationality, the horror hit closer to home than ever.

I don't quite know what to think of Halloween. I know that it's considered a classic, but I think it pales in comparison to the film that inspired it, Psycho, my favorite horror movie (I believe the slasher subgenre is one of the worst, yet I love the film that created it 🤔). Your article, however, is very well-written, as usual.