What I did on my pre-summer vacation

Talking Tarantino, Don Winslow, ‘Barry,’ and a new Chrisicisms series.

Thanks for hanging in during the last few weeks. I’d hoped to have a Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3 spoiler piece shortly before I left on vacation, but some scheduling conflicts kept me from a screening. I’m hoping to catch the film this weekend, and if I feel so inclined, I’ll write something next week.

But I won’t pretend to feel guilty about taking a break from content. After a few months of non-stop running, classwork, and obligations at home and the office, a long beach vacation was much needed. I spent a week “letting my soul catch up with my body,” as the saying goes, and it was healing and restorative. I’m back with a clear mind and renewed energy and enthusiasm for film writing, and I’ll reveal at least one of my summer projects later in this post.

I don’t have a lengthy idea to write about this week, but I did have some thoughts, as well as some pieces I’ve already put together for other platforms that I wanted to direct you to. So, let’s get into it!

Tarantino gets critical

Most of my vacation was spent by the pool or beach, which means I spent a lot of time with my nose in a book or three (much to the chagrin of my son, who complained, “you go on vacation to get away from learning”). One of those was Quentin Tarantino’s Cinema Speculation, a series of essays about a diverse array of films.

I wasn’t the biggest fan of QT’s last book, a novelization of his film Once Upon a Time … In Hollywood. While I applaud Tarantino for doing a novel that actually expanded his film’s world (so much so that the movie’s Manson family climax is barely a footnote), the sprawling tome was a bit too self-indulgent and meandering for my tastes. But its best sections were when the writer would go off on a screed about film history (even fake film history) and spend pages writing about actors, directors and their various choices. I didn’t want a novel from Tarantino, but I would have welcomed a book of film criticism.

That’s what Cinema Speculation is. I suppose you could also call it part memoir, part Hollywood history and part opinion piece, but it all adds up to a 400-page work of film criticism in the end. And it’s an absolute blast.

It’s no surprise that Tarantino’s a strong writer; his scripts are usually as strong as his visual direction. And anyone who thought he would adopt a more academic voice or focus on films that top the Sight and Sound list clearly doesn’t understand his appeal. Cinema Speculation is exactly what the director’s fans would want: a collection of rambling, energetic essays about films that QT loves; and, as you can guess, the focus is largely on exploitation films of the 1970s.

The result is a book that feels like the closest most movie fans will get to sitting down and talking films with Tarantino over a beer. QT spends a great deal of time talking Dirty Harry, Deliverance, Rolling Thunder, Taxi Driver and the post Texas Chain Saw Massacre work of Tobe Hooper. He goes on tangents about the careers of Burt Reynolds and Clint Eastwood, and spends an entire chapter speculating on what would have happened had Taxi Driver been made by Brian De Palma instead of Martin Scorsese. I wouldn’t say it’s a personal book, but there’s also enough detail about Tarantino’s family life to understand his love for blaxploitation pictures as well as his attraction to grindhouse throwbacks and “revengeamatics,” as QT calls them. You probably won’t leave understanding much more about what makes Tarantino tick as a person, but when you read his thoughts on these films, it explains so many of his directorial choices.

Out of all the books I brought on vacation, this was the one I couldn’t put down. Tarantino's energy and passion make it a breezy read, and one of the most purely enjoyable books about film in recent years.

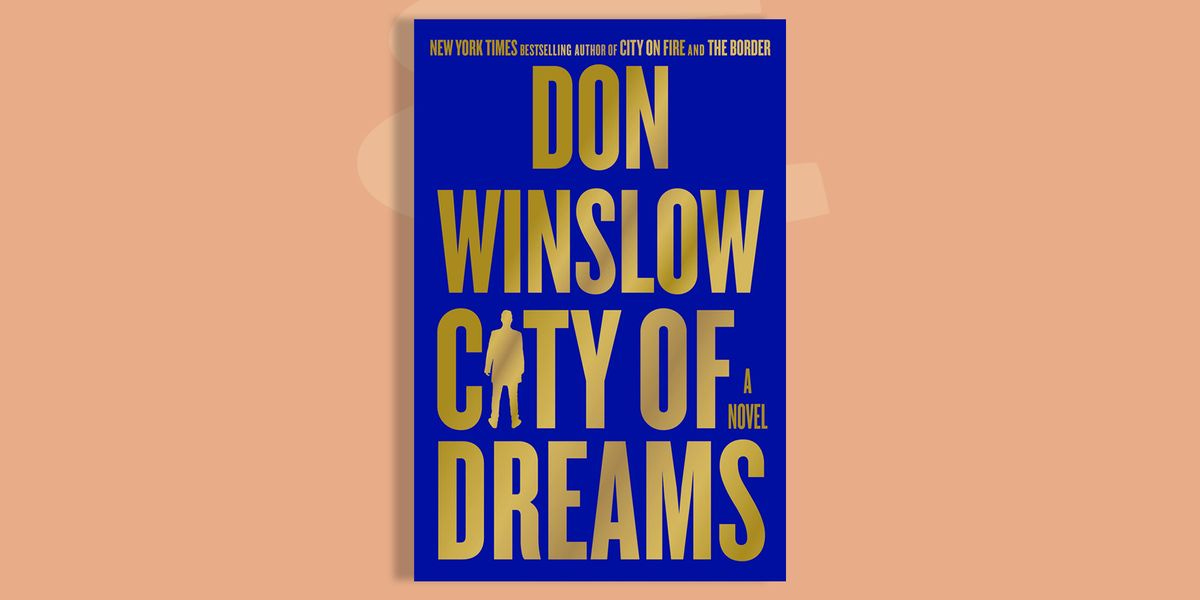

Winslow builds a trilogy

The other book I started and finished on vacation was City of Dreams, the second in Don Winslow’s “Providence” trilogy, which started with last year’s City on Fire and will end in 2024 with City of Ruins.

I only started reading Winslow a few years back, beginning with his dirty-cop epic The Force. I was instantly taken with Winslow’s hard-boiled prose, which mixes tough-guy preening with a sense of poetry. His characters are flawed, often doomed antiheroes, caught up in webs of sex, violence, drugs and corruption that will eventually lead to tragedy. He writes cinematically – I’m surprised more of his films haven’t been made into movies (so far, it’s only been Oliver Stone’s Savages and 2007’s The Death and Life of Bobby Z) – and mixes the violence and thrills with a sense of sadness and regret. The Force is my favorite of his novels, but I quickly scooped up both The Winter of Frankie Machine and his short story collection Broken, both of which I enjoyed, and I hope to start his famed Cartel trilogy soon.

The Providence trilogy is about Danny Ryan, a low-level thug in an Irish mob family in Rhode Island in the late 1980s. A loose retelling of Homer’s The Odyssey, it follows the events that happen when a beautiful woman sets the area’s Irish and Italian families against each other. As you might assume, it leads to betrayals, violence and death, but sets Danny up for leadership. City of Dreams follows Ryan immediately following the events of the first novel as he attempts to go straight, gets wrapped up in a CIA hit on a drug dealer, and winds up advising on a Hollywood movie about his life.

The trilogy often feels like Winslow Lite. The poetry is still there in places, particularly the heart wrenching final passages of the last novel. But the characterizations feel a bit more shallow than the author’s other works. Ryan’s an archetypal antihero; a violent man who also always seems to end up knowing exactly what to do, guided by a code of ethics he’ll never waiver from. Women are sex objects or one-note tragic figures. Mobsters and hitmen are too often just a step away from stereotypes.

And yet, Winslow has such a way with words and a knack for plotting that I didn’t really care. I breezed through City of Dreams, and its skin-deep themes made it a perfect beach read. The story wisely moves on from the tragedy-laced first entry, goosing it with some humor as Ryan and his men find themselves taking advantage of Hollywood execs and stars. I’ve been making my way through The Sopranos recently, and this should please fans of David Chase’s show; in particular, the bumbling Altar Boys’ misadventures in Hollywood reminded me of some of the funnier plotlines for Paulie and Silvio. Only in its final chapters, as the story heads for a rambling, surreal conclusion, does it fall apart. But I’m still curious where Ryan and his crew end up in next year’s trilogy capper.

‘Barry’ gets religion

Although recent busyness has kept me from many of my TV shows, one program I’m determined to stay up to date with is HBO’s dark comedy Barry.

I love watching Bill Hader as the titular hitman-turned-actor, and Hader’s also distinguished himself as a skilled director (he previously directed several episodes each season; this fourth and final season, he’s directing all the episodes). Barry’s a hitman convinced he can also be a good guy, and the most intriguing part of the show is often watching the character try to justify his own badness. The show – which also boasts fantastic performances from Sarah Goldberg, Henry Winkler, Steven Root and Anthony Carrigan – bounces back and forth between pitch-black comedy and drama, sometimes within the same scenes, and its explorations of abusive relationships, toxic masculinity and Hollywood phoniness have been balanced by gripping and often hilarious action sequences.

I’m not going to review the show or the season right now; maybe I’ll write something after the series finale in two weeks. But there’s an aspect of it I wanted to discuss. If you’re not caught up, you might want to skip to the next section, because there are going to be spoilers for the fourth season of Barry below.

The most recent episodes followed the leads of many recent television shows and took a massive jump forward in time to find Barry and Sally hiding out, raising a son in the desert. Barry is happy to teach his son about Abraham Lincoln and deter him from playing sports (one of the funniest moments finds Barry showing his son YouTube clips of horrific little league injuries),but Sally is miserable, having abandoned a career as an actress to work at a bar and raise a kid she’s unprepared for.

And, oh yeah, Barry’s an evangelical Christian now.

It’s actually a fairly large part of his new character. He prays with the family, watches services on TV and tries to model his life according to God’s will. Of course, when he decides it’s time to return to L.A. and kill his old acting coach, he searches podcasts for preachers who will tell him that murder isn’t really a sin (after much searching, he finally finds one, voiced by comedian Bill Burr).

This isn’t completely out of the blue – last season, Barry had a dream that convinced him he was going to be judged by God and sent to hell for his misdeeds. And while Barry’s desire to find a pastor who will give him permission to kill is largely played for laughs, it’s clear his newfound interest in spiritual matters is something he takes seriously. He wants to avoid hell and damnation; he also wants to use faith to justify his urges.

It made me think of the recent Netflix show Beef, where Steven Yeun’s character balanced affection for faith while also using his evangelical identity as a cover to commit crimes. The show captured a genuinely moving faith experience, and it never suggested that Yeun’s character was not truly searching for something to believe in … he just also couldn’t help himself from using that faith to get what he wanted.

Had these depictions of evangelicalism – a culture I grew up in and, despite some serious misgivings, still remain a part of – appeared twenty years ago, I likely would have been offended and written something about how Hollywood is once again depicting evangelicals as hypocrites. Now, after more than half a decade of Trump-ism, Christian nationalism and more, I’m not as offended – because I think we’ve seen that many evangelicals are hypocrites. But looking at my own life, I have to confess that I am, as well. I’m a person who, most of the time, genuinely wants to understand God more, spend time being more like Jesus, and loving my enemies. That said, I’m drawn to these things because I’m so aware that I lack in these areas. The tricky thing about faith is not trying to avoid hypocrisy – it’s realizing that the more you strive to do the right thing, the more your own hypocrisy reveals itself, and sometimes the faith can be twisted just the right way to keep you from doing the hard work of growth.

I’m fascinated by these more nuanced looks at faith. Most portrayals of Christians in entertainment tend to go to extremes; people of faith are either pious to a stereotypical extreme (think Ned Flanders) or hypocrites wielding the Bible to satisfy their own selfish desires (think The Righteous Gemstones). Certainly I know people on both ends; at different times in my life, I’ve been a person on one of those extremes. But I’m more fascinated by a take that acknowledges people’s genuine spiritual search as well as the ways that religion can be wielded and twisted — even without our awareness — to harmful purposes. In the wake of the last few years, I think it’s a conversation we need to be having about the largest faith system in America, and I hope we’re able to continue portraying the harmful toll of evangelicalism without tossing out the very real spiritual search that drives us.

‘Fast X’ thoughts

We’re officially in the summer movie season, folks. Like I said, I’m starting behind, having not seen Guardians of the Galaxy, Vol. 3 yet. But I did have the opportunity to screen the next big summer release, this weekend’s Fast X (pronounced Fast Ten because of course it is).

Longtime readers may know that I’ve been a fan of the Fast and Furious franchise. And while this tenth entry has its moments – particularly anything featuring Jason Momoa in a bonkers performance – I was largely disappointed with this latest turn around the track. But thankfully, it’s led to some great conversations.

You can read my official Fast X review over at CinemaNerdz. I also had the opportunity to join Kevin McLenithan once again over at the Seeing and Believing podcast while his co-host Sarah was away. As always, I had a great time chatting with Kevin about the weirdly difficult work of making such a stupid franchise successful. And if you’re not interested in talk about Vin Diesel, cars and Corona, we sweetened the deal by having a discussion about the 1947 noir classic Out of the Past, which I was quite taken with.

Coming June 2: Summer of ‘93

Finally, as I said, I came back from vacation with renewed vigor and energy for film writing. My class is done, I have a bit more free time now, and I have a few projects – including several for this newsletter – that I’m looking to implement. I’m not ready to share them all now, but I did want to discuss one project I’m undertaking this summer that I’m quite excited about.

There are certain years of moviegoing that I’ve considered instrumental in my life. 1996 was the year I had my license and the summer I was able to get into R-rated movies, and a few years back I wrote about the films of that summer. Many film nerds will agree that 1999 was one of the greatest years of cinema ever, and I’ve referred to it as “the year movies broke my brain;” I can’t explain what a joy it was to sit in a theater and watch The Matrix, Three Kings, Fight Club, Election, The Blair Witch Project and more. The first year I became a film critic and joined a critics society was 2007, the year that gave us, among others, There Will Be Blood, Juno, No Country for Old Men, and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.

But 1993 has always stood out in my mind as a significant year as well, which is kind of odd. I was only 13 that summer (I turned 14 halfway through), and it was when I transitioned from middle to high school. There’s no way I saw any of the R-rated fare that summer, and I can’t imagine I got to the theaters nearly as much as I would in later years, given that every trip required an adult willing to drop us off. But it was the summer of Jurassic Park, a movie that impacted me on such a chemical level at that time that it turned a strong interest with film into an obsession. It’s the summer I started reading Premiere magazine and the year in which I started getting into arguments with friends about the movies we just had to see. Yes, it was the summer of Spielberg’s dinosaurs, but it was also the year of the disastrous reception to Last Action Hero, the Tom Hanks/Meg Ryan romantic comedy classic Sleepless in Seattle, and the classic chase thriller The Fugitive. I didn’t see everything that summer, but it was the first year in which I was aware of everything coming out and paid attention to box office.

And so, 30 years later, we’re going to look back at that summer and some of its biggest films, beginning June 2 with the Sylvester Stallone action epic, Cliffhanger. I’m really excited about this series. Some of these films I haven’t seen in three decades; others, I haven’t seen at all. There’s going to be a bit of a Franchise Friday element here and there, as well as an approach to some films that has me really excited. So, look for that in two weeks.

Next week, I’ll have thoughts (hopefully) on GOTGv3, I should have a review of Disney’s Little Mermaid remake over at CinemaNerdz, and I have a few other things I’m mulling that I think will be pretty fun. We’ll get to it then!