Summer of ‘96: ‘Independence Day’ blows up multiplexes

The Will Smith charisma-delivery machine still charms.

The moment you saw the first trailer for Independence Day, you knew exactly where you’d be on July 3, 1996.

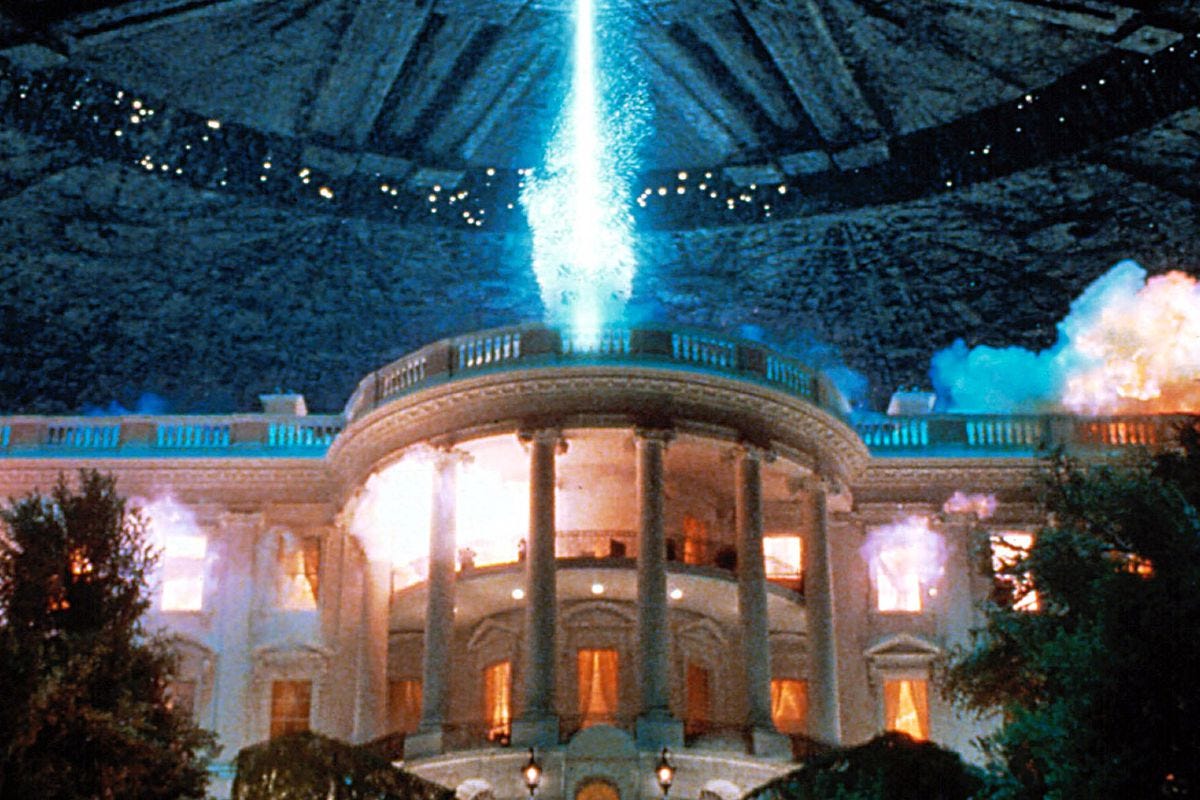

I was seated in the long-defunct Oakland Mall Cinemas. I can’t remember what I was watching, but I remember that trailer. When that flying saucer blew up the White House, I was hooked. I wasn’t the only one; the entire theater burst into applause. If you were paying attention to the temperature of filmgoers that summer, you knew that Mission: Impossible and Twister were just warm-ups. This was the summer of Independence Day.

And that held true. The film brought in $306 million at the domestic box office and $817 million worldwide. It kicked Will Smith’s burgeoning career into overdrive; the next year, Men in Black cemented his King of Summer status. It earned blank checks for director Roland Emmerich and producer Dean Devlin (who co-wrote the film) and launched an obsession with disaster films that eventually included Armageddon, Deep Impact, The Day After Tomorrow, Dante’s Peak and Volcano.

Independence Day kicked off a series of movies that revelled in the (unseen) death of millions, the decimation of global monuments and the end of the world, all played for sheer entertainment. For better or worse, it was one of the most influential films of the 1990s. It was a pop culture juggernaut, and one built without any previously existing IP or established movie stars. Audiences didn’t see it because it was a Will Smith movie or because the Independence Day brand had any cachet. They saw it because the trailer promised that Emmerich was going to blow up every damn city in the world, and they wanted to be there when he did.

Unfair reputation

In the two-and-a-half decades since its release, Independence Day has developed a reputation as the father of big, dumb movies. If Jaws and Star Wars proved that genre blockbusters could be original, smart and thrilling, Independence Day proved that they didn’t have to be those things to still make money. It could be derivative, irrational and just blow stuff up real good. The disaster films that came in its wake — not to mention every braindead followup from Devlin and Emmerich — further stoked the reputation that Independence Day was a bad film that opened the floodgates to even worse ones.

I’m not going to argue that Independence Day is a good film, at least not one that should be spoken of in the same sentences as Jaws, Star Wars or Raiders of the Lost Ark. But I do think that all of the things the film gets dinged for are either the things it was beloved for at the time or essential to its appeal.

The film tends to get knocked around as a silly, stupid and overly earnest bit of science fiction. It became supremely uncool to like it in an age where gritty post-apocalyptic sci-fi is one of the most popular genres at the box office. That’s what The Matrix wrought. And I’m all for that. I love meaty sci-fi that asks deep questions. I think Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds adaptation is one of the best alien invasion films of the last 40 years. And I can understand why audiences raised on Neo and The Hunger Games might roll their eyes at Independence Day’s sincere, one-liner filled script, and an ending that (spoiler) finds them taking down a fleet of alien invaders with the help of a computer virus and (checks notes) Randy Quaid.

But, of course, Independence Day never aspires to serious science fiction. Its roots are in the bombastic disaster films of the 1970s, and it simply uses the alien invasion as an entry into that genre. Admittedly, it’s a genre I have a fondness for. I love gigantic special effects that bring our worst nightmares to life, and the cast of famous faces that have to navigate them. It’s a type of film that goes down easy for me, and Devlin and Emmerich tap into that, making no excuses for any of its corniness and instead making that part of the joy of the enterprise.

Watching the film again recently, I was struck by how this movie would not be made this way today. It would be a ready-made trilogy or a streaming miniseries (I’m honestly surprised that Disney hasn’t greenlit a remake series for Disney+). You would have one film/episode dedicated to the impending invasion, another to the devastation across the planet, and then a rousing finale where the humans fight back. There would be an established mythology, set ups for sequels (hopefully better than the belated oneIndependence Day got), and a series of spinoffs dedicated to the various characters. I’m bored just thinking about it.

But that’s not how movies were made in the 1990s. Instead, the entire thing fits a trilogy’s worth of plot into two-and-a-half hours. Its cast is sprawling, following the President of the United States (Bill Pullman) as he leads the country through the attack and its aftermath, the tech whiz/cable installer (Jeff Goldblum) who figures out what’s happening, a random family in the desert whose patriarch (Quaid) has a past with an alien, and the hotshot fighter pilot (Smith) just trying to get back to his stripper-with-a-heart-of-gold girlfriend (Vivica A. Fox) and son. All this, and Harvey Fierstein, too.

I’m not going to praise Emmerich as an underappreciated director; he’s made too many terrible films for me to go too hard in defense. But it is impressive how well he weaves these stories without getting convoluted, and the movie allows its events to unfold deliberately. I was surprised how long it took to get to the sequence where the aliens actually unleash hell; it’s about an hour into the film. Prior to that, there’s a good amount of tension as the saucers appear, people try to figure out what’s happening and Goldblum’s character, David, attempts to warn the president. Even the central sequence of the spaceships destroying major U.S. cities lacks the quick cuts that films that came in Independence Day’s wake did. There’s a sense of scale and scope that makes it feel giant, otherworldly and even a bit horrifying — something helped immensely by the use of models instead of CGI work, for the most part.

The film walks a tricky line between making the devastation feel large-scale and impactful without being disturbing, keeping it in the bounds of entertainment without making it feel like we’re supposed to say “awesome” at the death of billions (Emmerich quickly became less good at this). Particularly after the Sept. 11 attacks, it became hard to watch any movie that showed mass destruction in a major city; the shot of random people plummeting from the Chrysler Building in Armageddon or the quick wiping out of millions at once in 2012 are the worst offenders. But Independence Day lacks that ghastliness.

Part of it is that the film avoids showing us anyone in severe agony, and I imagine it’s easier to take destruction from aliens rather than more plausible disasters like comets and global warming. But it’s also because each bit of destruction involves characters we’ve come to like, and the focus is on them escaping without dwelling on the awesomeness of the carnage. We see buildings get leveled, but there aren’t shots of people burning alive or being incinerated. We’re focused not on the decimation of Los Angeles but on the efforts of Fox’s character to escape; the White House blows up, but it’s empty and our focus is on the characters in Air Force One. Tonally, the film leans away from too much gravity; there are just enough jokes sprinkled throughout the tensest scenes (Judd HIrsch admiring the decor on Air Force One as the spacecraft bears town) to deflate the tension and remind you it’s just a movie.

A breakout cast

Emmerich and Devlin’s script has a solid structure, following each phase of the attack and response clearly. It’s less successful in creating actual characters. Everyone is a collection of catch-phrases and broad personality traits that help sell a type even if there’s no depth behind it. But thankfully, the film is blessed with a cast that understands the assignment.

This was far from Smith’s first movie, but it was the one that changed everything. Smith struts in supremely confident and funny, and he’s the centerpiece of the film’s most memorable moments (punching out an alien and then saying “welcome to Earth” might be the reason he’s still one of our biggest stars). He’s so good, so watchable that it’s easy to overlook the fact that there’s no character to Steven Hiller. It’s just a Will Smith charisma machine.

Smith is part of an ensemble that knows exactly the right notes to bring to their roles. Hirsch is a Jewish caricature in most of the movie, Goldblum’s nervous and constantly kvetching father, and he’s constantly just as funny as Smith. Pullman’s role is just to be the good guy, the man everyone wishes was their president. And while his character is fairly bland, Pullman steps up and flat-out crushes his big speech. Mary McDonnell elevates her damsel in distress with her intelligence and humanity, and Fox, in one of her first film roles, is a good foil for Smith’s charm. Even Quaid taps enough into his Cousin Eddie persona to create a loveable oaf.

If there’s a weak link, it’s probably Goldblum. Jurassic Park made him the go-to guy for compelling geeks. He’s admirablu dorky and funny, but hadn’t yet figured out how to combine his inherent quirkiness with the leading man roles. He becomes the film’s second romantic lead in the film’s back half, and never feels quite believable. The Goldblum of today would be interesting to watch in this (why haven’t we got an action film teaming up Goldblum and Nicolas Cage?); here, he’s largely a non-entity, which is only striking because of how watchable Goldblum is in everything.

Entertaining, if disposable

Over the last 25 years, I’d forgotten how much happens in the film, particularly the second act journey to Area 51. Emmerich and Devlin shift gears admirably, going from world-spanning destruction to some light sci-fi horror and then following it up with some Star Wars-inspired action (fun fact: the first time I saw any Star Wars footage on the big screen, it was before Independence Day, when they played a trailer for the special editions, which were released the following winter). Through it all, the film never loses its lightness. It goes for big moments — Pullman’s speech, Quaid’s last moments, the death of the first lady — that are suitably rousing and engaging.

In the moment, Independence Day still feels like one of the greatest movie spectacles ever made. It’s just that watchable. The build up to the invasion is still its strongest sequence, with the tension and mystery building and then released in a cavalcade of fire and special effects. But I also admired the restraint shown after the attack; the film allows the characters some breathing room and dwells on the devastation of humanity (to a point; this is still a movie where Will Smith punches an alien). And the film’s final firefight/assault on the mothership, while never approaching the heights of the dogfights in Star Wars, is still great fun. The laughs hit, the effects hold up and the cast’s charisma powers through the script’s weaker moments. My son watched it with me and informed me it was his favorite movie of all time, which is actually not something he says too often.

Of course, hours later, it had evaporated from my mind. What keeps Independence Day from being a blockbuster on par with Jaws or Star Wars is that it’s never too interested in sticking to the ribs. Spielberg’s shark movie has enough social commentary and sheer horror going on to keep it front of mind days after viewing it. Star Wars is deceptively simple, and yet the world-building is so effective that it achieves mythic status. Those films are pieces of artistry; even if there was nothing much deeper to them, you could feel their creators trying to do something new and difficult.

Emmerich and Devlin’s film seems to operate under the ethos that “hey, we’ll do this, it will be cool, and millions of people will see it.” And, I can’t say they were wrong. It is cool; it’s a lot of fun. Millions of people did see it. But I think that the film’s lack of ambition is also why it was largely relegated to being a movie we remembered seeing in 1996, lacking any staying mark on pop culture and not even getting any followup until twenty years later, as a last gasp at relevance by Emmerich and Devlin.

But hey, in the moment? It’s quite a ride.

The Digest

Where you can find me online this week

The CCM Canon: ‘Jesus Freak’ Was an Anthem; Was it Also a Problem?Over at Patheos, I started a new series called the CCM Canon, in which I’ll examine one song that was crucial to Christian culture. I started with a big one, as dc Talk’s “Jesus Freak” was inescapable for any ‘90s youth group kid. But despite the song’s outstanding hooks, I worry that it created a persecution complex in myself and others that we still see the residue of today.

Chrisicisms

The pop culture I’m loving

Rapture-Ready! Adventures in the Parallel Universe of Christian Pop Culture by Daniel Radosh: I read this as research for the writing I’m doing at Patheos. Radosh, a writer at The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, examines the weirdness of Christian pop culture. The writer, raised Jewish, is amused by how evangelicalism has created its own set of oddities, from a thriving music scene to creation museums and amusement parks to Christian wrestling, and he conducts a fair and thoughtful examination. I’ll admit some of this is the type of stuff that’s even too weird for me — I have no desire to ever visit the Creation Museum or take in a Christian wrestling match — and there are times when Radosh comes off a bit smug and condescending toward the weirdest and most offensive parts of evangelical pop culture. But he’s also happy to enter into dialogue and admit where he’s impressed and hopeful that the most judgmental and divisive elements of Christian pop culture can become more hopeful, loving and compassionate, particularly as he spends extended time writing about the Cornerstone music festival or talking with writer Frank Peretti. It’s always fascinating to see the culture I grew up in from an outsider’s perspective, and I appreciated Radosh’s funny and intelligent writing. My heart did sink a bit when I realized the book was written in 2008; I’m afraid any frustrations Radosh experienced with the culture clash back then have only been exacerbated in the last 13 years.

‘Salems Lot by Stephen King: One of the rare early novels by King that I hadn’t gotten around to. I think I just worried that vampires seemed a bit cliched for King. And you can’t ignore that his second novel owes a heavy debt to Dracula, not only in the vampiric myth but in the overall structure of the story. But two books in, King was already finding his voice and tapping into his knack for creating vivid characters and burrowing into the dark depths of small town America. Ben Mears isn’t his greatest protagonist; he’s King’s typical intelligent, intrepid novelist. But he’s only a small part of this sprawling collection of characters populating a damned Maine town, the rest of whom are vividly drawn and realized (aside from maybe the novel’s love interest, Susan, who largely just defers to her boyfriend). The book’s a bit of a slow burn, but once it becomes clear where things are heading, it explodes into one of King’s most terrifying and merciless tales (and the rare one with a solid ending). I flew through this one, although many nights I wished I hadn’t read it right before bed.

F9: The Fast Saga: If you’re not onboard with the adventures of Dominic Toretto and the Fast Family by now, I can’t imagine a ninth entry winning you over (I don’t even know how you’d begin to make sense of it). Director Justin Lin returns after taking the last two installments (and spinoff Hobbes and Shaw off), and his presence is definitely felt in the film’s absurd action sequences, particularly an energetic climactic chase involving cars and magnets. Once again, the franchise blends over-the-top action and dopey lunkheaded sincerity, but the formula’s starting to get a bit rickety. I like these characters, but Dominic Toretto lost what was most interesting about him when the series decided to turn him from a conflicted criminal into a superhero. If Hobbes and Shaw suffered because Dwayne Johnson’s snark and badassery were not leavened by Diesel’s earnestness, F9 suffers because its turgid flashbacks and soap opera melodrama lacks Johnson’s swagger to balance it out (much as Diesel and Johnson hate each other, having them both is essential to making this work, especially now that we’re lacking Paul Walker as a human entrypoint). Don’t get me wrong; there’s enough goodwill I’ve built with these characters and enough energy in the action sequences to make this a fun ride. But it never transcends the stupidity the way Fast Five or Furious 7 did. And as for #JusticeforHan? Let’s just say the film has an easier time explaining why they need to send a car to space than it does spelling out how the character is not dead after blowing up Tokyo Drift.

Luca: I don’t quite understand why Disney thought it was fine to take a film by Pixar, one of their crown jewels, and unceremoniously dump it on Disney+ instead of theaters, especially following one of their most highly regarded films in years. But i can understand why they thought Luca might be a bit too slight. Despite being about, you know, sea monsters, the film is one of the more leisurely and meandering films to come from Pixar. It follows two sea monsters (who turn into human on land) who become fast friends, enter a race and eat lots of pasta. That’s about it. And while Luca sometimes relies too much on formulaic standbys (I love Maya Rudolph and Jim Gaffigan, but I’m completely done with the over-protective parents subplot), but it’s still a low-key charmer. The setting is one of Pixar’s most beautiful, with the sun-dappled coastal villages and pasta that is maybe the best-looking animated food this side of Ratatouille. And while the film isn’t subtle in its message of tolerance and acceptance, it’s a moral that might need to be shouted these days. Luca isn’t top-tier Pixar, but it made me smile and I was surprised how much my kids embraced it.

That’s it for this week! Due to the holiday, there won’t be a Sundays with Spielberg this week. But next week, I promise to finally get around to my long-promised look back at The Nutty Professor and The Cable Guy.