Best year ever: ‘The Iron Giant’ is perfect

Brad Bird’s animated fable still thrills, moves.

It’s tempting to want to call The Iron Giant one of the greatest kids’ movies ever made. But to do that would be a disservice. Brad Bird’s animated film is funny, thrilling, thoughtful and moving in a way that few films – for any audience – manage. It juggles big ideas and navigates multiple tones, and it does so effortlessly. It’s at once a story of friendship, an atomic age adventure and an anti-gun fable — with a bit of discussion about the nature of souls. It is one of the greatest movies ever made, regardless of demographic or medium.

And, like many great movies, audiences utterly ignored it upon its release 25 years ago.

It’s shocking for many to realize that The Iron Giant wasn’t just a financial disappointment upon its release, but a straight-out bomb. Its financial failure is largely attributed to very bad marketing on the part of Warner Brothers, which had seen its animation division flounder with recent releases and didn’t expect anything of this little sci-fi family movie. They hemmed and hawed on release dates until it was too late to put together a marketing plan and do the requisite toys and Happy Meal tie-ins. When test screenings were overwhelmingly positive, WB scrambled to give the film a perfunctory release It was critically lauded, but theatrical audiences never caught on. It squeaked out $5 million in its opening weekend – good enough for ninth place – and collapsed across the finish line with $30 million worldwide on a budget of $50 million.

And yet, as with many great films, its quality ensured that it found an audience, and few today would deny that The Iron Giant is one of the great animated films. Despite the massive success he’s had with subsequent films, I think it’s Brad Bird’s best movie (and you’re talking to someone with a lot of love for The Incredibles and Ratatouille). When it’s compared to other films, the go-to isn’t another animated movie, but no less a masterpiece than Steven Spielberg’s E.T.

A boy and his robot

That comparison is accurate. Like Spielberg’s movie, The Iron Giant is about a lonely young boy who befriends a creature from the stars and protects it from the adults who can’t understand it. Hogarth Hughes lives with his mother in a small Maine town in the 1950s, the height of the Cold War. One night, he finds a 100-foot-tall metal man in the forest, tangled in the power lines. Hogarth saves him and strikes up a friendship with the creature, teaching it what it means to be human. The only person he lets in on his secret is Dean, the beatnik owner of a local scrap yard. Together, they must keep the giant safe from prying government agent Kent Mansley.

Even though he was born in the late 1950s and would have grown up a child of the Sixties, it’s obvious Bird has a ton of affection for Space Age pop culture. The giant’s design – especially when it unleashes its arsenal – feels pulled straight from old comic books and the covers of sci-fi novels. The soundtrack is a collection of ‘50s hits, but they’re deployed well without being too on the nose. The hand-drawn animation – I miss it so much – mixes the fantastical with charming, peaceful Americana, and I love how Bird and his animators play with perspective and scale, letting the height of the giant overwhelm us and giving us great moments of the creature looking out through the trees or, in one shot, towering over a small town in the background.

Like Elliott in E.T., Hogarth is growing up without a father, looking for a male role model. Bird understands just what kids find suspicious and what they find welcoming. Kent tries to ingratiate him with a bunch of “buddies” and “sports,” which annoy Hogarth (the quick montage of this is very funny). Dean, the junk dealer/scrap artist, talks to him like a normal person and approaches him on his level – in one of the film’s best scenes, he even gives him espresso. Of course, it might just also be easier to form a friendship with a character played by Harry Connick Jr. than one played by Christopher MacDonald. The fatherless setting isn’t leaned on as hard here as it is in Spielberg’s film, but it’s notable nonetheless.

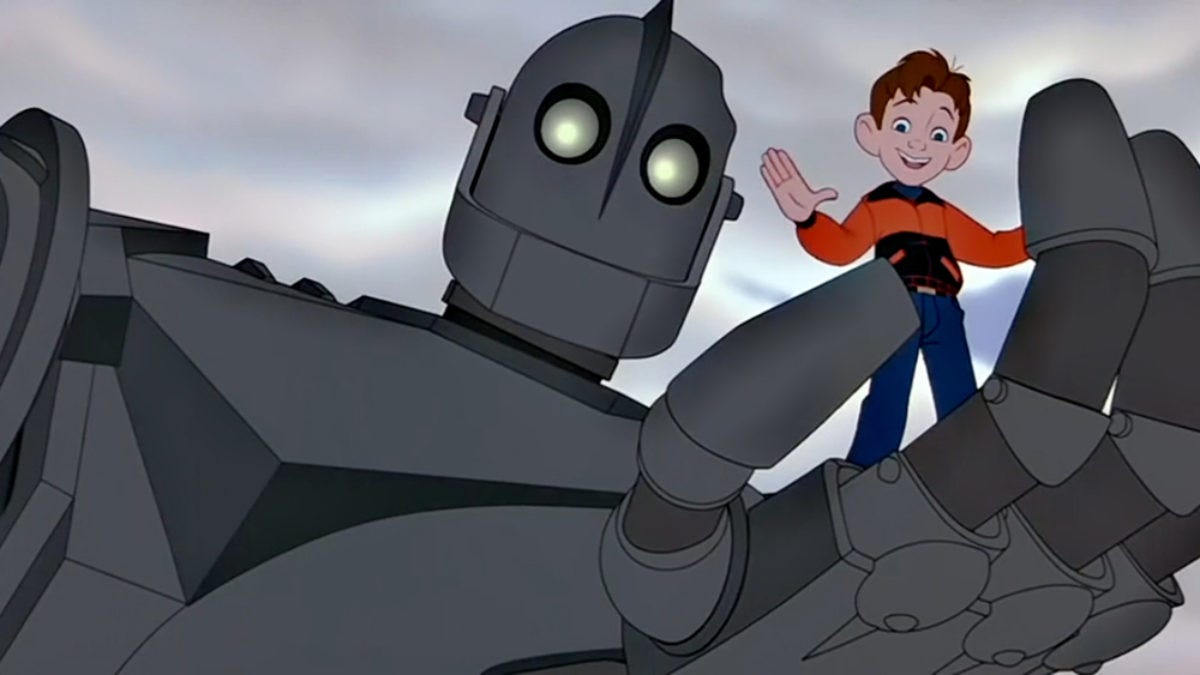

Hogarth’s key relationship, of course, is with the giant, and it’s probably not incorrect to describe the story between a boy and his giant metal dog. The giant’s fall to Earth has banged its head and caused it to not remember its objective. It’s a blank slate when it meets Hogarth, but strikes up a friendship based in gratitude after the kid frees him from the electric lines. There’s humor and sweetness in the sequences where the giant learns to mimic Hogarth’s expressions and learns to speak. And Bird indulges his inner child to explore just how awesome it would be to have your own personal robot. The animation strikes a balance between cartoony unrealism and naturalism; it’s low-key enough that much of it would work in live-action, but I appreciate the animation in the sequences where the giant cannonballs into a pond and clears it out, or spins Hogarth around in a junkie car like the world’s fastest carousel. There’s a beautiful sequence where the giant puts Hogarth in the palm of its hand and walks him around the woods. And it’s interspersed with clever moments like the montage in which Hogarth spikes Mansley’s milkshake with laxative, which kick in at the most inopportune moments in the agent’s quest to locate the giant.

The bones are there for a sweet, funny adventure, something on which The Iron Giant delivers. But what makes it a masterpiece is its deeper thematic question, which Bird has described as “what if a gun had a soul and decided it didn’t want to be a gun?”

“I am not a gun”

The giant, we learn, is capable of mass destruction when provoked, a twist Bird throws in during a shocking moment when Hogarth plays around with a toy ray gun. Alarmed, the giant’s defense sequences kick in, blasting lasers out of its eyes. Later, as it runs from the military, we’ll see that it has a host of other capabilities, including what appear to be nuclear-level bombs. But the giant has, thankfully, not fallen into the hands of a government that wants to wield it for its own whims. It instead meets a young kid who believes in heroes and villains and doing the right thing.

Early on, Hogarth and the giant are looking at comic books. The giant notices a metal beast on one of the covers. Hogarth scoffs and pushes it aside. That’s Atomo, he says, and lets the giant know that that creature is small potatoes, a villain created only to destroy. “You’re not like that,” Hogarth says, and then produces a copy of the Action Comics issue where Superman debuted. Hogarth tells the giant he’s more like Superman than Atomo. Later on, the two come upon a deer in the woods that is then shot by hunters. The giant encounters death for the first time and learns that guns kill. Later, the giant asks Hogarth whether it will die and Hogarth wrestles with whether the giant has a soul. Bird’s other animated films deal with adult materials in a clever way, but this is one of the most nakedly profound moments I’ve seen in a family film, and the giant exhaling “souls don’t die” as it stares at the stars moves me to tears.

It’s worth mentioning here how great Vin Diesel is in this movie. Diesel gets a lot of snark for his action movie performances, and some of that is deserved. But one thing I appreciate is his willingness to be sincere. He also knows the power of his voice. He’s been able to make three words carry different emotion and meaning in the Guardians of the Galaxy films, and as lunkheaded Dominic Toretto, Diesel’s actually really good in suggesting that, corny as it is, he’s all about family. I don’t think he’s been better than in The Iron Giant. The deep gravel of his voice is, of course, perfect for a 100-foot-tall robot. But there’s so much vulnerability in this vocal performance. When Dean chases the giant away after mistakenly thinking it’s attacked Hogarth, Diesel’s “I not a gun” is heartbreaking, as are the terrified “no’s” when the giant realizes what it’s done. And skipping to the ending, his delivery of “I go, you stay, no following” and “Superman” are gut punches.

The Iron Giant is a beast capable of great destruction that learns it only wants to help – as it does in the third act when it saves two kids who fall from a roof. It’s a weapon that wants to be more. As Hogarth tells him, “You are not a gun. You are what you choose to be.”

It’s a great lesson for the giant, but it’s even more profound for humans.

We are what we choose to be

Despite the fact that one is a PG-rated animated film and the other is an R-rated action adventure, the film has a thematic similarity to Terminator 2: Judgment Day, where the cyborg learns to be a protector instead of a killer. When watching The Iron Giant, I thought about James Cameron’s movie and the conversation between the Terminator and John Connor. “We’re not going to make it, are we? Humans, I mean,” John says. The Terminator’s response: “It’s in your nature to destroy yourselves.”

Earlier this year, I read Annie Jacobson’s Nuclear War: A Scenario, which uses research with military experts and former leaders to imagine what might happen if North Korea launched a nuclear weapon at the United States. The book kept me up at night for a week straight. It’s a grim imagining. Retaliatory anger, paranoia and bad information result in a world in which one bomb is followed by thousands of others, and humanity’s extinction is set into action within 90 minutes. Most of us would be dead only shortly after we learned the first bomb had dropped. It’s a chilling and sobering look at what fear and a quest to maintain power leads to.

The Iron Giant opens with a shot of Sputnik high above earth, and the film regularly pays attention to the fears of the Atomic Age, complete with ludicrous duck-and-cover drills and reminders that the Soviets were thought to be just minutes away from all-out assault. When the U.S. government discovers the giant, the first instinct is to destroy it – not simply because it’s a weapon of mass destruction but because it’s not their weapon of mass destruction. As Manley tells Hogarth:

“While you're snoozing in your widdle jammies, back in Washington we're wide awake and worried! Why? Because everyone wants what we have, Hogarth! Everyone! You think this metal man is fun, but who built it? The Russians? The Chinese? Martians? Canadians? I don't care! All I know is we didn't build it, and that's reason enough to assume the worst and blow it to kingdom come! Now, you are going to tell me about this thing, you are going to lead me to it, and we are going to destroy it before it destroys us!”

Of course, the desire to strike first and to combat (perceived) violence with violence is disastrous. Attacking the giant just causes its defenses to be raised and unleashes destruction. When Manley finally gets on the horn with Washington, even after his superiors have determined the threat needs to be dealt with peacefully, he overrides their rules and has The Bomb launched – which, of course, means that the bomb heads right to the giant, which is standing alongside a crowd of innocents in a peaceful U.S. town. Fear and violence result only in the potential death of innocents.

That’s heavy stuff for a family movie, and it’s amazing that Bird is able to fit all that in under 90 minutes without the movie feeling overstuffed or dour. It’s a kids’ movie that is preaches against guns – Bird wrote the script after the shooting death of his sister, and the original book was written by Ted Hughes to help his children cope with the suicide of their mother – and against violence, and culminates in a beautiful and moving moment of self-sacrifice (I won’t push the Christ parallels, but it’s notable that we also get a resurrection in the final shot). It’s funny and heartwarming, but it packs a hell of a punch.

And it’s a punch that’s still needed in a culture that’s once again angry and afraid. We’ve seen all too often recently how that can devolve into violence. Gun violence is still an epidemic, with mass shootings occurring daily. But we even weaponize the tools that should bring us together through social media.

But what if we could choose to be different?

Maybe a national viewing of The Iron Giant is in order to remind us before we react in our anger and fear that we get to choose who we want to be, and we should aspire to be more like Superman than Atomo.

👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻✌🏼