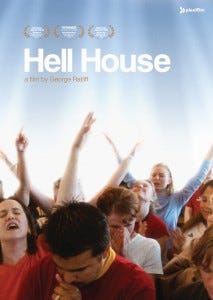

A documentary about extreme evangelicalism is more relevant than ever.

Revisiting George Ratliff's 2002 "Hell House."

George Ratliff’s Hell House (2002) resonates with me in a way few documentaries have. Its depiction of evangelicalism is strikingly familiar to the culture in which I grew up. When its church members speak about sin, salvation and Hell, I hear phrases that could have come from my own lips in my teens or twenties. As I’ve returned to the film over the decades, my relationship to it has changed. At first, I was sympathetic to the members of Trinity Church, located in Cedar Hill, Texas. Years later, I was frustrated. Now, I find their tactics horrifying and dangerous, a predictor of the culture-war Christianity that continues to consume our nation.

The film is a fly-on-the-wall look at the creation of Trinity’s annual haunted house, which is designed to literally scare the hell out of people. There are no vampires, zombies, ax murderers or goblins. Instead, there are gory, realistic depictions of suicide, school shootings, domestic abuse, drunk driving, and abortion. Hell Houses exist throughout the country, but Trinity’s was the most infamous — about 15,000 people annually spent $12 to see this real-life horror (it appears Trinity stopped doing its Hell House in 2018, but similar attractions still pop up here and there in the United States).

The idea is one of American Christianity’s more visceral — and controversial — evangelism tactics. The hope is that visitors will be so shocked and convicted of their sins that they’ll run sobbing into the prayer room at the end. It’s the Christian version of Scaring Straight. Several times throughout the film, participants talk about how fear is a part of salvation, and that they’re okay with the media thinking they just want to cause controversy — as long as people are getting saved, they’re doing the Lord’s Work.

Ratliff never mocks their sincerity. Hell House is not a Jesus Camp-style expose. It focuses on the believers at the center of Hell House and gives them their say; out of the film’s 85 minutes, only about five are given to non-believers’ complaints. The film opens with Trinity Pastor Tim Ferguson talking about the important work he believes the church is doing — he says that not telling others about Christ will send them to Hell, putting the blood on his hands (we’ll get back to that). There’s no tricky editing to show the members as hypocrites. The people profiled are not targets for lampoon. Their beliefs are real and treated without scorn.

So your take on whether Trinity’s Hell House is a good or bad thing is likely based on whether you believe in their brand of Christianity.

Though I grew up in a different denomination than the Pentecostal one Trinity subscribes to, the churches I attended in my youth were similarly focused on the Sinner’s Prayer and scare tactics. If my church had done a Hell House, I imagine I would have been eager to get involved. When I first saw the film, I was still at a point in my spiritual journey where I sympathized with the Trinity members. After all, if we believed Hell was the real final destination for those who don’t put their faith in Christ, then shouldn’t we take all necessary tactics to tell them how to escape that fate? And even if that approach is abrasive, can we really argue with the results (thousands of visitors are said to convert)?

Revisiting Hell House, I’m disturbed by the lack of nuance, compassion and understanding toward those who don’t share Trinity members’ beliefs and dismayed over a theology that smugly celebrates judgment over grace and love. I’m troubled because I see so much of who I used to be.

There’s a tone-deafness that pervades the Trinity members’ approach to modern culture. We see it early when they’re discussing whether to include same-sex relationships in Hell House and one church members states that it’s a pressing issue because “we get at least one lesbian couple at Steak N’ Ale every night.” A visual goof involving a Pentagram in the “Occult Scene” (which starts — as most occult problems do, I’m sure — with reading Harry Potter and Goosebumps) gives a good sense of how much insight they lack about the culture they’re trying to engage (they’ve accidentally drawn a Star of David instead). It often moves beyond tone-deaf into outright callousness. There’s a chilling scene where Hell House visitors enter a hospital room and hear a demon mock a gay man because he has AIDS. The scene takes place next to one where a teenage girl — with blood smeared all over her crotch — dies from a botched abortion. The girl makes a last-minute call to God and ascends to Heaven. The, who curses God for not approving of his homosexuality, goes to Hell. In probably the most blatantly offensive Hell House scene, date rape leads to suicide — the implication that attending a rave leads to rape and suicide, without ever acknowledging the victim, is deeply troubling.

Trinity holds to a black-and-white view of sin and humanity. While I’d agree there are some things — murder, adultery, abuse — that are point-blank wrong, this conversation normally requires more nuance and love than a haunted house, by design, can provide. There’s no room for competing theological perspectives, grace, redemption or sanctification except for the demand of an on-the-spot conversion. This heavy-handed approach is deeply problematic.

That’s to say nothing of Hell House’s smug view on judgement, particularly over issues in which even Christians are in disagreement. Their view of homosexuality can only lead to AIDS, despite the fact that many churches are full of thriving, passionate Christians from the LGBTQ community. In the black-and-white morality of Hell House, one drink leads to a car crash, whereas the Bible’s views on alcohol are more nuanced.

Hell House notably lacks a focus on the sins that are internalized and more common, particularly in the modern church. Where’s the cancer of greed or pride, or the soul-killing effects of being unkind, uncharitable and unloving? I’m sure the Hell House kids would say there’s nothing overtly scary or dramatic about those; I think it’s just a way of hiding the real evil that actually dominates most human hearts but would risk pointing fingers back at the congregation.

Shock-and-awe evangelism is contrary to the gospel. Christ dealt with sin not through terror but by inviting people into dialogue, showing what they were lacking and pointing them toward hope. The most effective evangelism I’ve seen comes not from hard confrontation but from relationships that display joy and hope. The problem? Those relationships call us out of our comfort zones, take time and come with no guarantees. It takes control out of our hands and leaves it in God’s.

Go back to that opening statement where Pastor Ferguson talks about sinners’ blood being on his hands. Who is Hell House for? Is it to showcase God’s glory — which is not done with fear and judgment but with worship, joy and praise? Is it to point others to Christ — which would involve compassion, humility and relationship? Or is for the Trinity members — to convince them they’re doing all they can, that they’re on the winning team, and to Hell (literally) with anyone who disagrees with them? It turns relationship-based spirituality into a numbers game. Instead of welcoming conversation, it forces an emotional response — which it often gets. But is that enough?

I remember a pastor once recalling how he interned for a revival conference his church was holding. They brought in a dynamic speaker and, at the end of the week, thousands of people went forward. A month later, he was responsible for calling everyone who had seemingly converted. Of the thousands who professed decisions, only a handful still went to church. When you force people to respond only emotionally to the deepest issues of the soul, you’re planting a seed in shallow soil. I’d be very surprised to find many Christians who converted at a Hell House and remained faithful.

But the film never treats the Trinity members as jokes, hypocrites or bigots. Ratliff spends time with several members to see their life outside the church. The film spends time with a single father of three. He takes us through the process of getting the family ready in the morning and then, in the middle of it, his toddler has a seizure. The family calls 911 and the father prays for the boy. By the time the paramedics arrive, he’s fine. Did the prayer heal him, or did the boy get better? The film doesn’t speculate, only observes. Later, when the man’s daughter begins dating, Ratliff allows her to talk about her love life. She expresses the traditional Christian views of abstinence, but the film never pokes fun; Ratliff gives her time to explain how her relationships work and that it’s not necessarily as tightly wound as it seems. It’s a fair portrayal.

And it’s fascinating to watch the teens and adults approach their Hell House roles. Some have truly found catharsis in it, such as a woman whose work in the suicide scene once brought her face-to-face with her rapist and opened the door to forgiveness. One church member describes the dissolution of his own marriage and sees similar scenes enacted in the event — he ends up making his own trip to the Prayer Room. There’s the sense that maybe Hell House does some good, even if only for the people involved.

But there are also problematic elements as you watch the teens audition for the “suicide scene,” “abortion girl,” and other Hell House staples. They approach their roles like it’s high drama — the church even has an Oscar ceremony to award the best “performances” at the end of the season. But do they realize they’re taking real-world tragedy and turning it into a bludgeoning evangelical tool? Do they think about the victims they’re portraying — the person who’s been date raped, who’s wrestled with suicide, who is questioning their sexuality — who may have flashbacks or be disturbed by this? And what does it say about compassion and Christianity that they can take the very real, complex dilemma of faith, salvation and issues of the soul and turn it into a one-dimensional horror show? And why are they so attracted to playing these tragic roles — do they feel compassion and need? Or is it their opportunity to tip-toe as close to these forbidden actions as possible?

Hell House works because it doesn’t thrust these questions on the viewer. It doesn’t announce an agenda. It observes and naturally brings questions to the surface. People with no background in evangelicalism may find it hilariously corny and misguided. People involved in churches like Trinity may find this to be a validation of their beliefs. But I belief most people will walk away with some skepticism, wondering what good the members think they’re doing.

I’ve talked before about my dislike for evangelical films. I don’t think art should bludgeon with messages. I don’t think you should preach to the choir. The thing that continues to fascinate me about Hell House is how it holds a mirror up to my beliefs and my past, and asks me to consider my own thoughts about how faith and culture should engage each other. It’s a fascinating movie; it becomes more so each time I watch it.

So many thoughts. I probably should see this film soon.

1) Are documentaries like Hell House capable of being made today? The problem is you have to trust your audience, *knowing* that your film is going to be used for purposes you find abhorrent. Do we have a space for that?

2) Much more provocative: the question of what "justifies" an artistic use of trauma is a fascinating one. There's a smug evangelical teenager in me (certainly not the majority) that says "wait, it's justifiable to use horrific trauma in the context of art, but not in the context of facilitating a literal approach to God?" And to be honest, from within the sinner's-prayer framework I once was within, I don't know that there's a good answer to the question. I remember feeling convicted when I read an interview with the producers of the recent Pilgrims Progress animated film. They said something to the extent of, "yeah, our craft is a bit shoddy, but there are Christians all around the world who really want this, maybe even need it, for whom the core message of the book can be transformative. And so to be honest, even if we were given twice the money, we'd probably just make two films like this rather than one with more artistic excellence." I don't particularly like The Pilgrim's Progress (to put it mildly), and I'm not their audience, but--man, that does seem to me to be what it looks like to use film as a medium of service to one's neighbor, rather than to Integrity or Art or Ego. I had a similar opinion (though more negative-slanted) about the Sherwood Pictures films. I hated the theology and orientation and artistry of their films. Yet their commitment to body diversity in their casting? Their focus on actors as human beings rather than perfect icons of a director's vision? Behind-the-scenes, I kept thinking "this production seems way closer to following Christian ethical ideals than, say, the Hollywood defaults that infect Silence or Children of Men or even Les Innocentes.

I don't have any answers here, of course. When I see a film that feels like a perfect expression of a unique vision, done with integrity and courage, I am in awe. I can't but say, "this is a director/project that, were I in Holywood, I would sacrifice for." These things feel important in a way almost similar to the feelings about the school where I teach. And I want to theologize this; I want to fly some flags, saying that "Christianity always prefers complexity" or "we create in the image of which we're made" or "this Leaf will point people towards Heaven, and the tree be found in Paradise." But I keep wondering--as Tolkien did--whether and why, at the end of the day, a beautiful painting is more valuable than a scrap of canvas used to keep your neighbor dry.

Not that Hell House does that; Hell House is convenient in that it is mistaken about its aims. One can complain rightly that Hell House's problem isn't its lack of nuance, but that even the conversions it does produce are unlikely to stick, whereas its alienation and damage to the Gospel might be more long-lasting.

But it does, as the Conspiracy Theorists say with their inane social media posts, "make you think." :-P

I haven't seen the Hell House film, but I agree with all your reasons why that kind of evangelism is unhealthy. Yes, Jesus spoke about Hell and its terrible consequences, but this is too much. There's a similar mentality among some pro-life people of showing pictures of aborted children that I don't agree with either.