Franchise Friday: The Matrix Reloaded (2003)

'The Matrix' goes weird, the Wachowskis go deep, and there's a mud orgy.

Sequels are safe.

That’s not to say I don’t like them — I wouldn’t be doing these Franchise Fridays if I didn’t. And it’s not to say they can’t be surprising; every once in a while, you get a Spider-man 2 or Empire Strikes Back that improves on the original or throws a wrench in our expectations. But by and large, the rallying cry of sequels is to do the same thing again, just louder and bigger, and in a way that doesn’t harm the franchise.

Marvel has perfected this. I think many of their sequels are a lot of fun, and Guardians of the Galaxy, Vol. 2 might be my favorite film in the MCU. The studio understands just how much to open up the universe with each ongoing story, but it’s also incredibly careful about not killing off characters or doing inalterable harm to the bigger picture so that they can keep making more movies. The MCU is a ton of fun, but it also plays by rules that ensure its continuation, which means the films don’t upset audiences and don’t close off future possibilities.

Lana and Lilly Wachowski would make a horrible fit with the MCU.

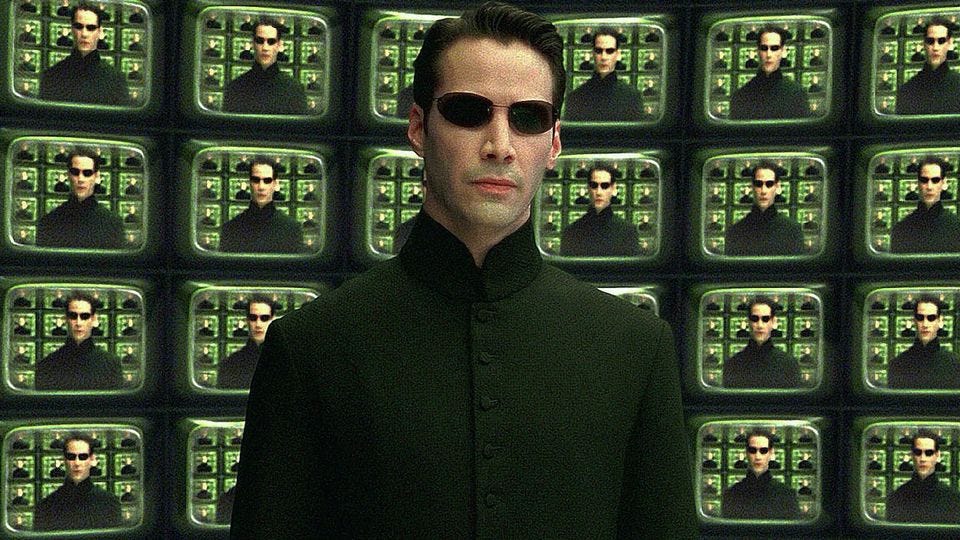

There’s a reason why, when people talk about The Matrix, they tend only to refer to the 1999 original. That blockbuster set imaginations on fire and left audiences buzzing about the possibilities of what would come next. When Neo finally believed he was The One, audiences could not wait to return to see him lead the war against the machines, free the human race, and do some more gravity-defying kung fu.

Instead, what the sequels delivered — in addition to the kung fu — was a deeper dive into the philosophy and workings of The Matrix, a climactic and jargon-heavy exposition dump, and a muddy cave orgy. The Matrix Reloaded was a financial success, earning nearly $300 million, but it’s rarely talked about in the same excited tones as the first film, and it set the third movie in the franchise up for disaster later that year.

Watching it again for the first time in 18 years, I understand why audiences were disappointed. The Wachowskis’ film suggested a larger, but more troubling, world behind the first film, and dismantled Neo’s hero’s journey. There was a bit less badassery and more navel-gazing. There was too much story, and the action strained the bounds of credulity, even for science fiction. More than anything, the Wachowskis seemed to take glee in going against audience expectations, and didn’t care if everyone left the theater utterly confused, an attitude that they would push even further in the same year’s Matrix Revolutions.

All of that is still true. But maybe it’s just watching it with nearly two decades’ of hindsight or being refreshed by a sequel willing to break the formula, but I found a lot to enjoy in this sequel, and think it’s a worthy follow-up to the 1999 game-changer.

A fascinating mess

That’s not to say The Matrix Reloaded isn’t a mess. There’s entirely too much plot, the pacing’s erratic and the Wachowskis’ reach often exceeds their grasp when it comes to the action sequences. It’s too much, but at least it’s too much of a good thing.

Like many others, I expected The Matrix Reloaded to follow Neo’s call from the end of the first film. He issued a challenge to the machines at that moment, telling them he was on a mission to free as many minds as possible and bring the war to an end. I’d hoped the sequel would follow the revolution as Neo and his cohorts ran amok in the Matrix.

Instead, the Wachowskis give us a team of revolutionaries that are tired and nearly broken. They’ve freed minds, but at a cost; the machines are getting closer to Zion. Where The Matrix implied that Neo was the chosen one all of Zion had been waiting for, The Matrix Reloaded suggests that Morpheus is seen as a crazy zealot, and there are many who believe he’s wasting time and risking humanity on his religious quest. Meanwhile, Agent Smith has returned and is no longer tied to the machines; instead, he’s absorbing programs and growing stronger as he does. Neo, meanwhile, is doubting his own position as Messiah and plagued by dreams of Trinity’s death.

It’s a lot, and I haven’t even mentioned the Oracle and the Keymaker, new characters like Niobe (Jada Pinkett-Smith), or the Merovingian and the suggestion of werewolves, ghosts, and vampires in the Matrix world. Rather than deliver a straightforward action story about taking down the Machines, the Wachowskis double-down on their philosophical musings and examine the tension between free will and control, and they create new complexities in the mythology, including rebellious programs, elaborate backdoor hackings and sentient viruses, constantly stopping for lengthy exposition dumps.

It’s not that The Matrix wasn’t also complex or prone to philosophizing; that was kind of its appeal. But the exposition was deftly delivered, dressed up in visuals that called to mind television commercials. Here, we get a lengthy sequence in which our three heroes sit in a posh restaurant and listen to a Frenchman go on about control, culminating not in an action sequence but a sexy dessert. And the Smith subplot doesn’t go anywhere in this film except to set up an action sequence halfway through and a cliffhanger; it could easily have been excised or saved for the very end to set up the third movie.

Perhaps the portentous pondering would have gone down easier if the film’s pacing wasn’t so off-kilter. The film stops cold for long conversations on park benches, in the bowels of Zion, at restaurants or in hallways. Then, it picks up for action sequences that last ages, giving us some zip for about 20 minutes before lurching to a halt again. Nothing in these sequences is particularly bad, and the philosophizing is often interesting. I love the idea that an older, more horrific version of the Matrix may have led to ghosts and vampires, or that there are rogue programs trying to avoid deletion. And all of this adds to the film’s themes of free will, fate and control. The execution is just a bit clunky.

And those action sequences are pretty incredible. The film’s centerpiece is a four-way martial arts battle in the Merovingian’s lobby, and it’s immediately followed by an all-timer of a chase sequence involving cars, semis, motorcycles and samurai swords. Together, the scenes take up about 30 minutes of screen time, and feel like an exciting, inventive evolution of the first film’s approach to action, reveling in slow motion, wire work and exquisite choreography. But it’s almost too much of a good thing; by allowing each sequence to play out one after another instead of cutting back and forth, they become wearying. It’s exhilarating but exhausting, and comes close to toppling over into absurdity, although the sheer audacity of it keeps it on just the right side of ridiculous.

Less successful are the scenes involving Neo fighting a variety of Agent Smiths. The Matrix pushed the boundaries of what was possible in CGI in 1999. The Matrix Reloaded wants to do the same thing, but can’t quite push through. The much-vaunted “Burly Brawl” goes on forever, but the computer-generated Smiths and Keanu Reeves’ digital-assisted moves look like cartoons, becoming self-parody about the time Neo swings on a lightpost to kick a bunch of Smiths. A final fight in a blank hallway is a bit better, but not by much. I understand the Wachowskis’ desire to go even further in this film, but they’re constrained by the limits of the technology.

And really, when I think about what’s wrong with The Matrix Reloaded, it’s that overabundance of ambition. The Wachowski’s want to go bigger with the story, deeper with the ideas, crazier with the special effects. And throughout the film, you can feel them struggling to hold onto it. It’s an unwieldy beast, held together by sheer will, and I understand why it repelled many fans of the original. But I kind of love the grandness of it all. The Wachowskis never give us what we expect and by the end of the second film, they’ve revealed that the story they told in the first film was not as special as we thought, just another element of control programmed into the Matrix. I can understand why many didn’t like that.

Egro, vis a vis, concordantly…

While I’ll agree that The Matrix Reloaded has flaws, I won’t go so far as to call it bad. And I think many of the things people hate the most are actually the things that work best, and are key to taking it into a new direction.

And that includes the mud orgy.

Ask anyone who saw The Matrix Reloaded what they remember about the film and some might talk about the action, others may mention the Architect, but everyone remembers the sexy time in a cave. It comes about 30 minutes into the movie, after Neo, Trinity and Morpheus return to Zion and Morpheus delivers a rousing sermon of hope. The people of Zion let loose in a feverish dance and Neo and Trinity retire to a secluded alcove for some alone time. Watching it again, it’s less an orgy than a rave, interspersed with Neo and Trinity’s love scene. And it caused snickers you could hear a mile away; it was cringe before the term was invented.

But I think it has less to do with the graphic nature of the scene — it’s not that graphic at all — and more with how a scene of passion feels at odds with the cool, affectless nature of the first film. With The Matrix, much of the appeal came not just from watching Neo in gunfights, it was the calmness with which he sauntered in. The movie was all cool grays and blues; the rave scene is almost embarrassingly fervent, filmed in warm glows. If people snickered, it was because The Matrix wasn’t associated with anything this seemingly sincere, unironic and passionate.

And yet, hindsight provides a great tool. Because while Lilly and Lana Wachowski broke onto the scene as cool and idea-driven, their subsequent work has been marked by warmth and humanity. Speed Racer is remarkably silly and warm-hearted, Cloud Atlas is bursting with sincerity. Their Netflix series Sense 8 has the requisite fights (and, yes, orgies), but it’s also an unironic exploration of human connection. If The Matrix allowed the Wachowskis to explore their nerdiest philosophical ideas, The Matrix Reloaded sets them up to explore what really interests them, and that’s the question of what makes us human and what’s worth dying for.

The central tension that plays out in The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions is whether the often irrational, undashable hope possessed by humanity is any match against the unfathomable intelligence of The Machines. The cave scene is the one moment in the franchise up until now where humans are able to take a break from their fighting and remember what they can do that the machines cannot. They can love, they can be passionate, they can do something frivolous. This is what they’re fighting for; the chance to be fully alive.

And that’s the only real glimpse we get of unbridled humanity in this film (the next film explores this more). Because the majority of The Matrix Reloaded is about stacking the deck against them, and showing just how overmatched they seem to be.

The Oracle seems a bit more aloof this time than she is in the first movie. She’s revealed to be another program, one created to be intuitive of human behavior. Can she be trusted? Is she truly helping Neo and the humans, or is she just another form of control? Is Neo’s quest to find the Key Master essential to saving humanity, or is he just being sent on a fetch quest? Throughout the film, there are questions of determinism, musings on control. There are hints that Neo is not the first “The One,” and the visit with the Merovingian (a fantastically French Lambert Wilson) reveals that not only were there previous versions of The Matrix, but that the idea of control is baked into every line of code.

This all culminates in the final sequence with The Architect, which is the other moment that messed with audiences’ minds. Many couldn’t believe the fim would end with a lengthy, near-indecipherable conversation. Others just couldn’t understand a damn word The Architect said.

And while the sequence is lathered in big words and jargon, it’s not that hard to follow. Basically, The Architect reveals that there have been several iterations of The Matrix, and Neo is in the sixth. Each century, this causes the Matrix to reboot. The computers realized that free will was the core problem that caused the system to fail, and an anomaly brought about one person in each simulation who could control the code; therefore, the computers designed a system that would manipulate this person into eventually returning to the Source, whereupon the human rebels would be destroyed and the simulation would start over again. Failure to return to the Source would ultimately destroy the Matrix and all of humanity.

The wrinkle this time is that Neo’s predecessors were driven to make their choice and save humanity out of a general love for all people. Neo’s love expresses itself in a more specialized form, his attachment to Trinity. Most of the Ones who came before chose to return to the Source; Neo chooses to go the other way and save Trinity, even if it means the destruction of Zion and the human race, and sets the question up that Matrix Reloaded will have to answer: is Neo’s love and hope enough to stop machines that have become “quite efficient” at destroying humanity?

I can see why audiences may have been troubled by this; it takes a cool and cerebral film franchise and makes it seem a bit saccharine. But why rely on machine-like precision and emotion? Isn’t the argument that there is something about humanity that can cause it to rise beyond its machine captors? Sure, it’s an awkward fit with the first movie, but that’s the point. The Wachowskis don’t feel pressure to cave to audience expectations, and they have the freedom to take this in whatever weird direction they want. It might be a messy effort, but I respect the ambition.

Of course, none of this holds up if The Matrix Revolutions is terrible. And my response to that one as the credits rolled in 2003 was “what the hell?” So next week, we’ll discuss whether the Wachowskis’ gambit pays off.

Related Franchise Fridays in this series: