Is Lars and the Real Girl the only film to sincerely ask its characters “What would Jesus do” without making me cringe?

The question comes from the pastor of a small congregation to a group of largely older parishioners. In 2007, the time of the film’s release, the WWJD fad had long passed. The question feels sincere; I believe that this congregation might be a decade behind Christian culture and organically wants to know how to act like Jesus. It also helps that it is centered on quite the conundrum: What do you do when someone in your community believes a sex doll is their true love?

The miracle of Craig Gillespie’s film is, as Roger Ebert said in his review, its faith in human nature. This movie could easily go in a number of crass directions yet it never wavers in its belief that love and goodness have the power to heal. It’s a mini-masterpiece of kindness.

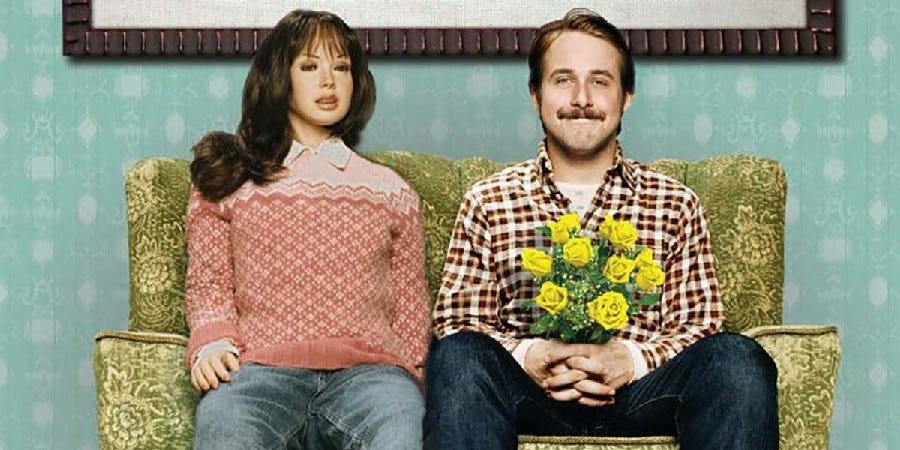

Lars (Ryan Gosling) is a young man in a small Midwest town who lives in the guest house behind the family home owned by his brother, Gus (Paul Schneider), and sister-in-law, Karin (Emily Mortimer). He’s closed off from everyone else, apparently leaving home only to go to his job or to church. Karin regularly begs him to join them for breakfast or dinner, but Lars always finds an excuse. When bubbly young Margo (Kelli Garner) says hello at church, Lars tosses a flower into the woods and runs away, lest she think he’s interested.

Gus and Karin get a twinge of hope that Lars might be coming out of his shell when he announces that he has a girlfriend coming in from out of town. What they find instead is that Lars’ guest is a sex doll he purchased online. Her name is Bianca, and Lars explains that she’s a missionary who uses a wheelchair and cannot speak English. Because of her religious beliefs, Lars says she shouldn’t stay with him and asks if Bianca can bunk at Gus and Karin’s. The couple has to figure out how to navigate the situation, with Karin attempting to play along and Gus worried his brother is having a mental breakdown.

This premise would be a disaster under the wrong direction (actually, given Gillespie’s subsequent filmography, I’m surprised we got something so wholesome). But Gillespie, working from a script from Nancy Oliver, guides it with a gentle hand. Although everyone understands the true reasons for which Bianca was made, it’s strongly implied that Lars does not use her for those intended purposes. Instead, through her, Lars feels more normal, and it opens opportunities for him to integrate himself into community.

He’s just Lars

This does not work without the right lead actor, and it’s one of my favorite Gosling roles. This was shortly after the actor became a heartthrob in The Notebook and firmly within his stretch of playing tortured, troubled men in films like The Believer, The United States of Leland, Half-Nelson and Blue Valentine. Lars isn’t without his darkness – he’s a ball of phobias who’s erected walls because of his mother’s passing during childbirth and his father’s recent death, which the film hints was a suicide. Gosling doesn’t play Lars as tortured but with a sweetness that’s been his secret sauce in comedies like The Nice Guys, Barbie and The Fall Guy. Lars is nice; probably to a fault. He has a nervous smile beneath his mustache and worries about Karin catching a cold in the winter weather.

Lars wants relationship and community but fears the vulnerability and entanglements that come with it. As someone who struggles with social anxiety, albeit not as severely, and has especially noticed in conversations with my therapist that much of my fear stems from the belief that I’ll say or do things incorrectly, I sympathize with the way Lars seems almost in pain when someone asks him a question or touches him. Yes, Lars is afraid of losing people – his mom died at a young age, and that fear is behind his constant concern for Karin and the baby she’s carrying. But Lars also believes he’s not fully formed, not grown up. A conversation with Gus late in the film shows that Lars isn’t quite sure what makes him a full-fledged man. His mother’s death seems to have convinced him that whatever he does could harm others. It’s not overplayed; the film never overdoes its explanations, but it makes it clear why he ends up forming a relationship with a plastic doll. Bianca’s an emotional connection, someone who won’t criticize or make fun of Lars. She listens but requires no risk. Gosling is fantastic in suggesting all of this without sacrificing Lars’ gentle sweetness.

Community healing

Karin and Gus ultimately connect with the town doctor (Patricia Clarkson), who suggests that since Lars isn’t harming anyone, everyone should play along and treat Bianca as a real person. I’m not a psychiatrist, so I can’t vouch for whether this is an ideal or effective mode of treatment. But as a narrative device, it creates opportunities to show how choosing compassion over judgment can heal not just one person, but an entire community.

What’s refreshing about Lars and the Real Girl is that it’s infused with a tender optimism that people will, by and large, do the right thing. Yes, Paul initially struggles with playing along, but ultimately his concern for his brother wins out. A few townspeople joke behind Lars’ back, but there’s usually someone who quickly sets them right. In what is one of the most refreshing depictions of a church body at its best, a few parishioners grumble but are ultimately pushed back by one of their stalwart volunteers, who reminds them of all the oddities they and their family bring to the table and yet the church loves and accepts them as they are. There are a few instances – such as a bowling outing with Lars and Margo – in which it appears someone might hassle Lars, but the film overwhelmingly tilts toward positive outcomes (they stay and bowl with the two).

And the townspeople don’t simply just go along with Lars’ insistence that Bianca is real. They find ways to engage her in the community – she “volunteers” at committees, “models” in a store window, and “reads” to children. By loving Lars and meeting him where he’s at, the community creates opportunities for empathy and finds a connective tissue that seems to energize them just as much as it forces Lars to connect with others. The psychiatrist treats Bianca’s “illnesses” as real, and uses the appointments to talk to Lars. I love how Gosling plays the reaction Lars has, suddenly finding himself in conflict with Bianca as he subconsciously begins to realize that what he’s really aching for is true community and love, not the kind with no risk or commitment.

Again, the film never overplays its hand. There’s a tentative friendship with Margo that suggests a potential flirtation, but Gillespie is wise enough never to make romantic love be the thing that breaks Lars out of his spell. Rather, Lars finds himself growing jealous of Margo’s new boyfriend and then consoling her after a breakup; after they go bowling together and Lars realizes that a relationship would mean cheating on Bianca, the fractures in his relationship with her begin to grow more pronounced. But it’s all in Lars’ timing. And while the townspeople accept Lars’ relationship with Bianca, they also never let it cater to his own worst impulses. When he throws a fit because Bianca has a volunteer dinner on their Scrabble night, the same church lady who called her fellow congregants to task puts Lars in his place about his own selfishness.

And slowly, Lars begins to heal. To ask questions about what it means to take responsibility and live alongside others. To show up for dinners with his brother and sister. And to experience true friendship. None of this would have happened had everyone in town told Lars that Bianca was nothing more than a piece of plastic or forced him into an institution. And the community benefits, with their empathy opening opportunities to show love and support making them more joyful and closely knit. It never once feels too twee or cloying; the movie never loses its sincerity and compassion.

We have a hard time loving people correctly, and there are several movies that provide examples of how to love those who are hard to like. And yet, sometimes even harder is knowing how to correctly love the people we care deeply about. We want the quick fix, the tough love to snap them into place – we especially don’t want something that causes us to appear too vulnerable, leave our comfort zones or risk looking silly. It’s often harder to meet people where they’re at, indulge them and refuse to cast judgment – even if, in many cases, that’s what they need. Lars and the Real Girl shows us how to love the odd and troubled. And in doing so, it shows how we might also find new joy and community. This is a gem.

LOVE this movie, was so surprised by how well its premise works.