When I was a teenager growing up in fundamentalist Baptist culture, my parents were fairly strict about the art I consumed, particularly when it came to music. I spent hours at Bible bookstores in those days, searching for the newest releases from dc Talk, Jars of Clay and Audio Adrenaline. You could find certain Christian albums at Target or Wal-Mart, but the selection at a Christian bookstore was much larger. As my faith developed in my twenties and I thirsted for deeper doctrinal works, those stores were one of the few places where I was assured to find the latest by theologians I loved. It was through them that I was introduced to Caedmon’s Call, Donald Miller and John MacArthur (I may have some regrets). A good portion of my paychecks during my single days went right back to those stores, which catered to my little cultural niche, selling items that I was guaranteed were “safe” and soul-satisfying.

During my time as an underpaid journalist (is that redundant?), Family Christian Stores served as a part-time job. On nights and weekends, I worked as a cashier/customer service associate. I did it for three years, weathering several Christmas seasons, Easter rushes and Kirk Cameron releases. I’m sure I was fairly grumpy about it; I wasn’t happy to have to work two jobs. But I have good memories. I worked with fun people and built some friendships with the high school and college kids on staff. I was able to buy one book half off each month. And being able to help someone buy their first Bible is still one of my favorite memories. I wasn’t sad to go when I got a job that allowed me to have just one employer, but sometimes I do get nostalgic for the retail world.

And yet, it was during my twenties that my disenchantment with Christian subculture started, and it’s probably no coincidence that it all began during my employment at Family Christian, which closed its doors for good in 2017.

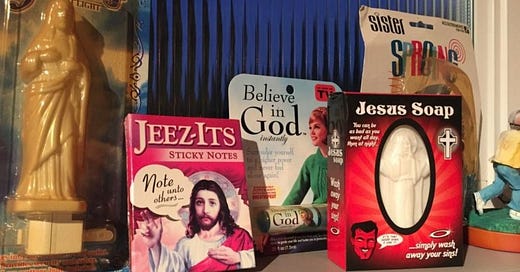

Some of this was definitely due to being in the annoying early stages of Calvinism, where I thought it was my responsibility to sniff out every false doctrine and heresy. So I often complained to my colleagues about the smiling face of Joel Osteen on our shelves or the fact that a postmodern Brian McLaren book was located next to a book by John MacArthur that warned about the Emerging Church movement. Fully in the “cage stage” of the Reformed movement, I wondered why we sold Catholic books and items in the store. I decried all the trinkets as Jesus junk and cringed at the borderline copyright infringement on the T-shirts. And this…well, to me, this was unforgivable:

But aside from my theological pedantry, there were legitimate issues. Management was highly concerned with sales, and associates were required to hit targets on DVD, CD and book pre-orders or the number of $5 bargain items we sold during a shift; employees were disciplined and even fired if they failed to hit these targets. Given all the Bible has to say about debt — not to mention the fact that I was working a second job partly because of my own problems with that — I had major issues about cashiers being required to push credit cards onto customers. Granted, none of this would be out of place at any other retail store; it’s part of being a business. But in their correspondence between employees and customers, Family Christian positioned itself as a ministry. However, it seemed to blur the lines between commerce and service whenever it saw beneficial. Stores opened on Sunday, which is odd in a market where even evangelical-beloved Chick-Fil-A is closed one day a week. During the Christmas season, it was difficult to spend time with family and friends because you worked nearly every Sunday. I remember working one Christmas Eve at the store (it was required) and we were the last place in our strip mall still open. Even Starbucks closed before us on Christmas Eve, and few of us were able to make it to church services or family gatherings — all so we could work at the Christian bookstore.

But more than that, I began to feel a distaste about the whole mixture of faith and commerce. I wouldn’t go so far to say that it was the equivalent of changing money in the temple, but something certainly felt wrong about turning deeply held beliefs into a profit scheme. There was a Bible for every demographic, Jesus Junk for every home. It was hawking evangelicalism; and if it had to mix and match doctrine or keep the shelves stocked with Conservative biographies and patriotic memorabilia to keep the cash coming, so be it. Family Christian Stores’ idea of what it considered “Christian” seemed to be based around whether it had PG-rated language and whether it fit whatever the culture’s idea of evangelicalism at that time — which, at that time, meant a lot of Joel Osteen, Sarah Palin and Duck Dynasty stuff. It wasn’t a spiritual respite so much as an evangelical stereotype that got franchised out.

And never mind that quality never seemed to be a concern; although, to be fair, retailers benefit more from something’s popularity than whether or not it’s good. But if Christians believe that they should give God their best, Family Christian never seemed to line up with that belief. Walking in, you could take a tour of some of the most laughable, cringeworthy aspects of Christian culture, from its simplistic novels to insipid music to poorly made films. What’s worse is that it was like walking into an evangelical bizarro world, where everything was a funhouse mirror image of “real-world” items. There was music that sounded kind of like what you’d hear on the radio; it might not be as good, but at least it was clean, right? There were horror novels that never got too intense and wrapped things up with a conversion experience or spiritual victory. There was clothing that looked just like the brand names you saw in stores, but with a Jesus-ified tweak; a Good and Plenty logo that said “God is Plenty.” The idea was that the retailer knew that its shoppers enjoyed things of the world, and they provided items that were copies of that, but were “safe.”

And perhaps that’s what became my biggest issue with Family Christian Stores. It contributed to this “us vs. them,” culture war mentality that has been one of the worst things about American Christianity in recent years. It gave credence to this lie that the world outside the church was bad and should be avoided, and instead of allowing Christians to be part of the world, the salt that preserves and seasons it, it became another way to keep that salt in the shaker. It was a bunker that allowed them to avoid contact with sinful unbelievers and bolstered their beliefs that they were right (and righteous) and everyone else was wrong. Sure, not every item sold there was bad, but the overall isolationist mentality is part of what’s been to blame about this divide between Christians and people of other faiths these days.

Still, its closure made me sad. It made me sad because many of my friends worked for the store and lost their jobs. I lost a nostalgic tie to my own teenage years. I was sad because there are people who found their first Bibles there, and they’ve been blessed by the books and even music sold there. Sure, they can get all that online these days, which is likely what led to the closure in the first place. But while I find the store’s existence more problematic than helpful, it did provide a place for Christians to have community and find items that blessed their souls.

I am enjoying your writing and can relate with too many experiences. Might want to correct “forest” to “first” toward the end.