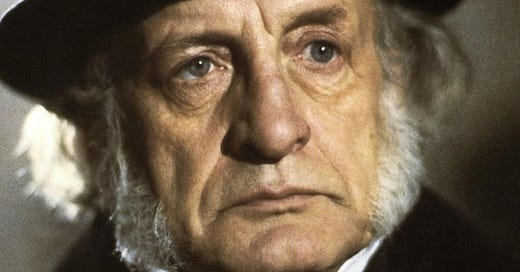

Is George C. Scott the best Scrooge?

The 1984 telling of 'A Christmas Carol' is among the best adaptations of the tale.

On the Fridays leading up to Christmas, Retro Reviews will take a look at various film adaptations of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

A Christmas Carol is one of the most beloved tales in the English language. We know its scenes by heart; they’ve become part of our culture, often from childhood, when we first saw Mickey Mouse as Bob Cratchit and Jiminy Cricket as the Ghost of Christmas Past. Aside from the Bible, I don’t know if there’s a more famous redemption story.

That’s part of the reason why so many straight adaptations of it feel so dry and rote. We’ve seen Scrooge go through the steps of hatred, haunting and humbling so often that without a twist — the Muppets, Bill Murray, a CGI Jim Carrey — it feels lifeless, like eating your Christmas vegetables. It’s not that Alistair Slim, Patrick Stewart or Albert Finney are bad in their roles; it’s just that by now playing Ebenezer is a thankless task.

Which is why Clive Donner’s 1984 telling of the tale feels so refreshing. This version — possibly the best cinematic adaptation of it — never feels like it’s going through the motions. It is respectful of Dickens’ tale but also feels vibrant, alive and soulful in a way that many others don’t. And in George C.Scott, Donner may have found the rare actor who could bring to life Scrooge’s misery while also rendering him a three-dimensional human being.

Sure, the hallmarks are all there. There’s the ghost of Jacob Marley warning Scrooge about the three spirits. Tiny Tim is accounted for. There’s the visit to Scrooge’s doomed romance, and a check in with his nephew, who of course is playing games at Ebenezer’s expense (a touch I’ve always felt mean-spirited in every adaptation). Everything culminates at Scrooge’s graveside before the old miser’s joy is reawakened and it’s all wrapped up with a “God bless us, everyone.” The story is here, but the version feels more energetic and urgent than it usually does.

Much of that is due to the way Donner and Scott humanize Ebenezer Scrooge. For once, we see him at work outside his counting house, conducting business at the bank and sticking it to some investors. Where many versions turn him into a caricature of greed and anger, Scott gives us a man who’s less angry and more cynical. A faint smile at a remembrance of Christmases past, a bitter retort; Scott’s Scrooge is believable as someone who wasn’t always so miserable but whose life has been marked by reversals and misfortunes that choked the joy out of him. This means that not only do we believe his redemption is possible — we’re rooting for it. Most adaptations tend to treat Ebenezer Scrooge as a villain who becomes a hero; in Donner’s version, he’s a disillusioned man who we want to see wake up.

This is crucial to our investment in the story. For Dickens’ tale to still have power, we need to see it not as fable but as cautionary tale. We need to be able to imagine ourselves in Scrooge’s situation and understand the ways we’ve let our own cynicism and self-preservation blind us to the needs of others or bury our sincerity. This might be the rare A Christmas Carol telling where I see Scrooge as a fellow human being, someone I recognize; in my most honest moments, I might see myself. That humanity is why George C. Scott has, in recent years, been acknowledged as the definitive Ebenezer Scrooge.

This is also one of the only versions of the story to remember that, at heart, A Christmas Carol is kind of a horror story. Donner leans into the gothic terror of Dickens’ tale. His Marley is ghastly, with a drooping jaw and dead eyes; when he escapes Scrooge’s room via the window, the soundtrack is filled with the wails of other ghosts. The Ghost of Christmas Past is ethereal and beautiful, but with a touch of severity to her. The Ghost of Christmas Present is booming, often angry at Scrooge for the way he tramples on the good day. A sequence often cut from these tellings, when the ghost reveals the emaciated children Ignorance and Want, is stark and scary, and of course the story’s final passages have their own gloomy horror.

It’s not a perfect telling. The BBC television values leave it feeling a bit stuffy and stagebound in places, and the urchin-like Tiny Tim is the one area where it leans into cliche. But I don’t know that there’s been a version of the story able to avoid these pitfalls. The 1984 A Christmas Carol both preserves the power of Dickens’ story and makes it feel like we’re hearing it for the first time. It’s a fantastic adaptation.

I'm Team Sim, myself, but I enjoyed your article!

George C. Scott was the Best!